A while ago, I encountered a note on contemporary dance provided by ChatGPT. It said, while traditionally contemporary dance could be referred to an assortment of Western techniques, it is now a means for addressing current socio-political-cultural issues, reflecting the diversity of contemporary society via inclusion of varied forms, content, and identities. Though not off-the-mark, I found the definition reductive, leaning towards a temporal description while solely crediting the West for its technical root. It emphasised the lack of contextualisation of contemporaneity existing within the dance community in India.

It is best to admit that there is no singular definition of this genre. However, we can indeed agree upon a few characteristics such as plurality, diversity and a multiplicity of forms and aesthetics. To these, I would like to add what I strongly identify with contemporary dance — critical thinking. These characteristics make it difficult to fit this genre into an ‘organised sector’ and even harder for a contemporary practitioner to concretely contextualise her work in history.

Notable changes

From Kathak-turned-contemporary dancer and choreographer Daksha Seth’s work ‘Sari’

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

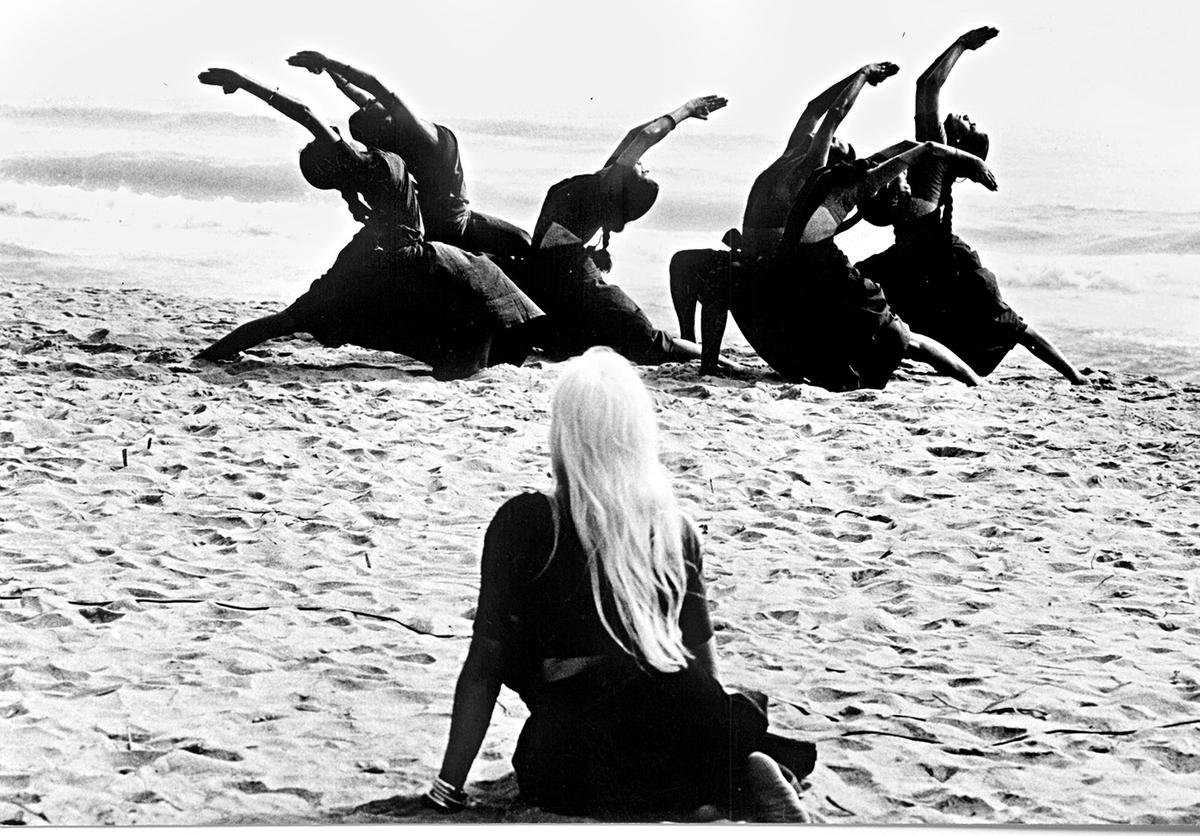

Dance scholars have studied two significant moments of change in the Indian modern/contemporary dance context, where classicism has been interrogated to be replaced by new politics as well as form. The first phase, referred to as ‘Indian modern dance’, was led by Rabindranath Tagore, and ended as a thriving process perhaps with Uday Shankar (1900-1980). This school of practice freely and openly adopted heterogenous dance styles from both East and West and remained open to the idea of modifying past traditions. The second phase which heralded the use of the term ‘Indian contemporary dance’ began in the 1980s with the arrival of Chandralekha, in Chennai, and others including Kumudini Lakhia, Daksha Seth, Maya Krishna Rao, Astad Deboo and Manjusri Chaki Sircar (by no means is this list exhaustive) in various parts of the country. These choreographers had a foundational training in one or more classical forms. Their work was marked by a conscious need to depart from tradition, yet not in a way that mimicked contemporary dance in the West. The post-colonial need to define ‘contemporaneity’ in their own terms through their own forms was urgent among them.

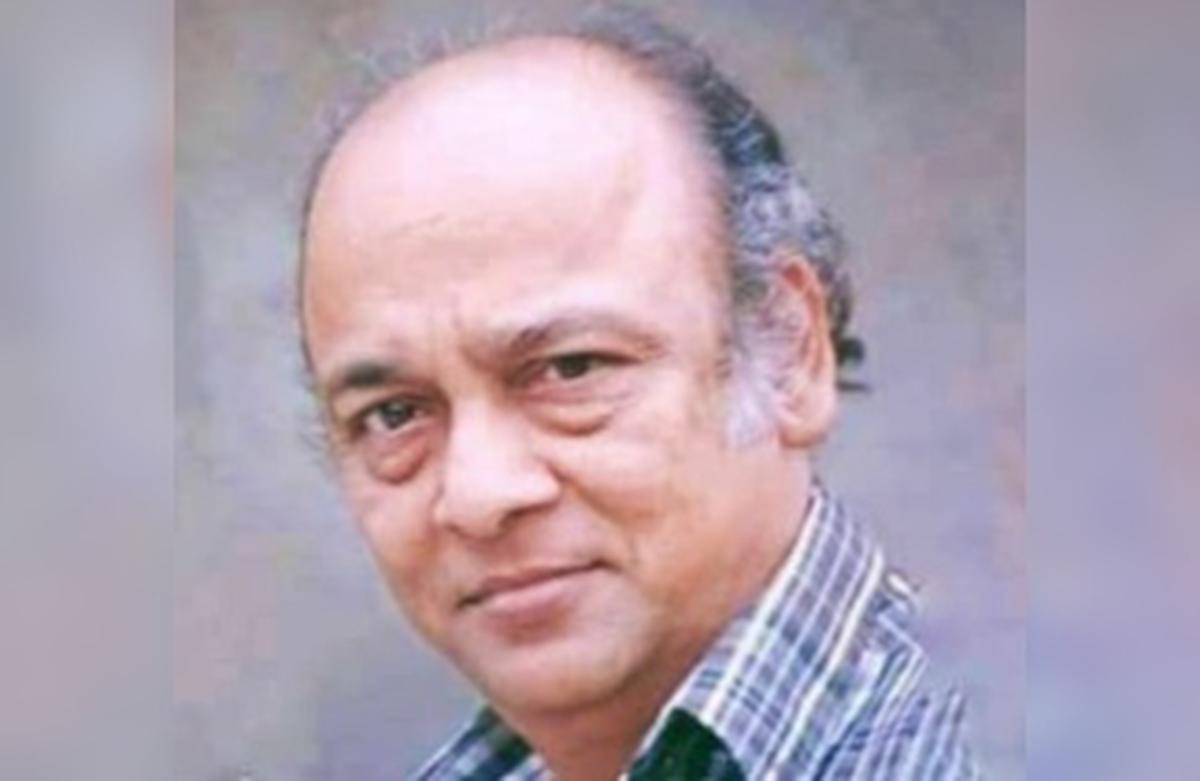

Forging new frontiers

Contemporary dancer and choreographer Jayachandran Palazhy at the Attakkalari Centre for Movement Arts (ACMA) in Bangalore

| Photo Credit:

K. Murali Kumar

Post-’90s, dancers such as Jayachandran Palazhy, Anusha Lal and Mandeep Raikhy returned to India after several years of training in British dance schools. Through Attakkalari and Gati Dance Forum, they facilitated access to contemporary dance for those with little or no training in Indian classical forms. The hierarchy of classically trained dancers was broken. Dancers trained in popular Western forms, film dance, yoga or martial arts enrolled for contemporary dance courses and fairly soon became dance-makers themselves. While this was a much-welcome intervention at the time, in this need to constantly define, create pedagogy and institutionalise, one started to see a renewed standardisation. ‘Contemporary dance’ became yet another category, full of recognisable tropes and cliches rather than politic. There has remained, however, a presence of a small counterculture of moving away from the ready-made aesthetic in order to forge new performative modalities — often in process, tentative, asking questions rather than hurrying to provide answers. Through such works, contemporaneity becomes not just the identity of the ‘dance product’, but an entire philosophy and critical process.

Space for new ideas

For the past 12 years the collective I work with — Basement 21, has tried to create space and platforms such as March Dance festival to nurture these conversations around process, perpetually willing to reframe the ‘contemporary’ for ourselves and our audience. But an urgent lack remains for different pedagogies that can potentially bridge the gap between theory and practice, past-present, East-West, in a productive, rather than binary manner.

Padmini Chettur

| Photo Credit:

Lorenzo_Palmieri

These pedagogies to address the double lack of a concrete definition of contemporary dance and of its critically documented history should be complementary to the choreographic practices. Such separation and integration of theory and practice are well-tested methods in academia especially for experimental/creative disciplines. But in India, the onus of ‘educating’ dancers falls solely on the choreographers . Alternatively, the responsibility falls on the dancers, who are often searching without direction, resources and peer discussions. This, in my opinion, is as much a challenge for practitioners as the other well-discussed issues such as lack of funding or rehearsal/performance spaces.

Need for proper training

Contemporary dance is taught in India either as a style in a dance institute or through choreographic processes shared with dancers. For numerous logistical reasons, these training moments are neither of a long enough duration nor rigorous enough to provide tools enabling dancers to create. As a teacher and a co-curator of March Dance festival that now offers a grant to emerging choreographers, I encounter this often that many young dance-makers are oblivious to even the basic formal and technical choreographic developments in the last hundred years, and therefore are struggling with dated queries or resorting to imitating existing works knowingly or unknowingly. For contemporary dance to grow into a research-based investigation rather than a product-oriented reinvention of the wheel, the pedagogy around it must include the complex colonial-post colonial-modern-postmodern histories and practices that have preceded us.

Chandralekha watching her dancers do ‘Namaskar’ on the beach, 1992

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

In my attempt to demystify contemporary dance, let me add a few words defending the accusation of abstraction and exclusivity that contemporary practitioners often encounter. I believe that a creative form must thrive within debates. A performer, whether narrating a story or not, is still in dialogue with the audience. He/she is not necessarily the showrunner but is vulnerable in her effort to communicate. In the words of German dancer Susanna Linke, “Dance is walking on the edge of the stage, not safely in the centre.”

At a time when the need for conversations around plurality and inclusivity are at the forefront of all socio-political debate and the bastions of unchanging tradition seem to stand on contested and shaky terrain — now more than ever, there is a need for contemporary dance to become a practice of response and resistance. For this we must consider strengthening its foundation. If not, we will continue to see bodies only capable of aspiration, never in complete ownership of their own contemporaneity.

The writers are contemporary dancers and a part of the collective, Basement 21.