[ad_1]

There are three movies from my youth that shaped how I felt about space: E.T., Cocoon and Independence Day. While the first two presented extraterrestrial life as wrinkly, cute and more or less benign, watching spaceships obliterate the White House didn’t give me the best feeling about what was out there in the universe. It was a fear that persisted through much of the late 90s as I watched Apollo 13, The X-Files and Species.

Clockwise from top left: Stills from Independence Day, The X-Files, and E.T.

But for many of my fellow millennials, sci-fi shows and movies were a welcome escape from the mundanity of daily life. Bengaluru-based writer and illustrator Vinayak Varma grew up watching Star Trek. “I loved the show’s vision of a utopian federal society that’s taken to adventuring in space only after having solved Earth’s most pressing problems. Its optimism comes from the relief of having truly transcended all human limitations,” he shares.

Susmita Mohanty, a space architect, spaceship designer and serial space entrepreneur based in Bengaluru, remembers watching Cosmos on a black-and-white television set on Sunday mornings, and being moved by the philosophy of the show. “Carl Sagan’s poetry and philosophy have shaped me and my belief that science cannot exist in a silo without the arts and humanities,” she says.

While astronauts Rakesh Sharma, Sunita Williams and Kalpana Chawla captured the public’s imagination, ISRO and its scientists didn’t really figure in our lives. That’s changed in recent years, thanks to A.P.J Kalam, high-profile missions such as Mangalyaan and Chandrayaan, and ISRO’s own more public-facing communications strategy.

Illustration from Menaka Raman’s new book, How to Reach Mars and Other (Im)possible Things

| Photo Credit:

Illustration: Rajiv Eipe

What the children are saying

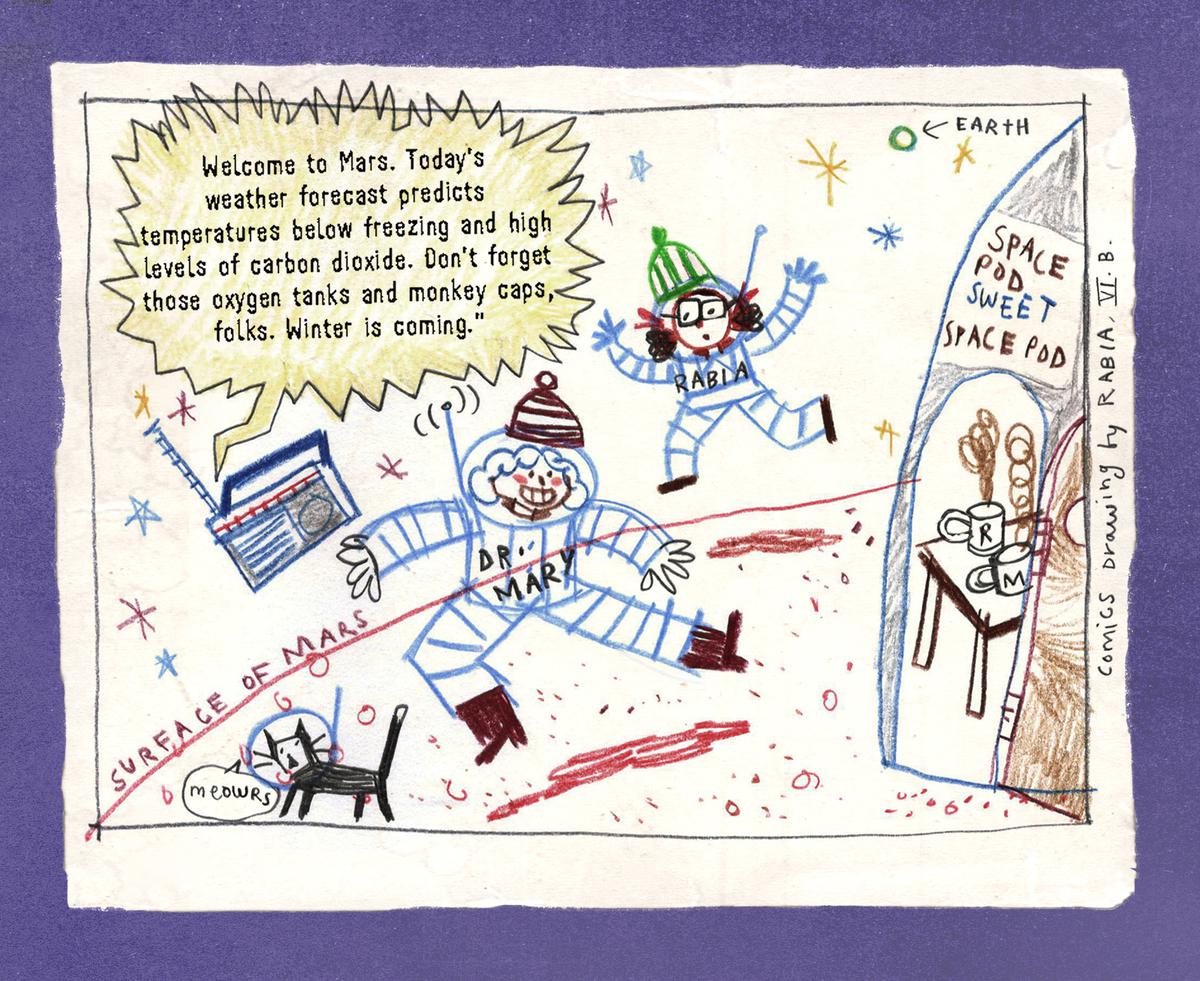

As someone who has written two books for young readers about space exploration (the irony is not lost on me), I’ve interacted with hundreds of children from across the country and I’m always curious to know what they think of the future of space exploration.

The younger ones, such as Nirbhik Aravindan, a seven-year-old from Mumbai, would probably be the first to sign up for the starship Enterprise’s next expedition. He says, “I want to live on Uranus because it’s mysterious and no one knows much about it! And I want to visit all the gas giants, too!”

On a recent visit to a school in Bengaluru, I asked students of Class V if they’d want to move to Mars. The answers ranged from the practical to the profound to the flippant. One child cheekily said that they’d consider it “only if there’s Swiggy and Netflix on Mars!”. Another professed that he would only move if his family and friends did.

Pranavi, a 12-year-old studying at an international school in Bengaluru, felt that our desire to colonise other planets was the worst kind of running away. “Why should we get a chance to live on another planet when we can’t take care of our own? We’ve destroyed Earth, we should stay on and fix things here.”

Meanwhile, Aarush Kar, a 13-year-old from Kolkata, shared that there are some things children didn’t want to know about “like the sun dying”, but understanding things like the space-time continuum was cool.

We need more space stories

Susmita’s father Nilamani Mohanty was an ISRO scientist and she recalls growing up in Ahmedabad around “space guys working on ISRO projects” and contemporary architects. “If you juxtapose architecture and space together, you have space architecture, which is a discipline I’ve specialised in. But it wasn’t just one thing, it was more of an ocean of things that shaped me,” she says.

While researching my recently-published book on the Mars Orbiter Mission, How to Reach Mars and Other (Im)possible Things, illustrated by Rajiv Eipe, I had the privilege of speaking to a number of retired ISRO scientists. They frequently visit schools in smaller towns and cities, talking to students about the space organisation, and share with pride how at the end of their sessions, students queue up to ask them how to become an ISRO scientist. Perhaps these interactions, shows such as Rocket Boys, and more children’s literature around space science and exploration will fuel the imaginations of the next generation of scientists, with a context and setting they’re more familiar with.

A scientist’s take

“After Chandrayaan and the Mars missions, students are excited about space exploration. A lot of youngsters ask me how to join ISRO, how to study at the Indian Institute of Space Science and Technology (of the Department of Space) in Valiamala, 20 km from Thiruvananthapuram. They ask me when ISRO will be able to land Indians on the moon and Mars.”

(On the race in India to ‘buy’ lunar land) “Some Indians, including film stars, are buying land on the Moon. But the U.N. treaty on outer space states that space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, does not belong to any particular country or individuals. It belongs to all of humanity. Some agencies such as the Lunar Registry claim they sell land on the Moon. This is illegal. Nobody can claim ownership of land on the Moon.”

P.S. Veeraraghavan, former director, Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre, Thiruvananthapuram

(as told to T.S. Subramanian)

While ‘grown ups’ from around the world make plans to set up space stations on the moon, buy patches of lunar land, and continue to litter space with space debris, young people seem to have a more measured view of what we should be doing. And thank Mars for that.

The writer is a children’s book author and columnist based in Bengaluru.

[ad_2]

Source link

possible%20Things.jpg)