Languages have become a hot topic in India today, with a battle for linguistic supremacy raging across the country. But to constrain the nation’s linguistic diversity into monolithic grids is an impossible, and ill-advised task. With what would you replace words such as tahsildar, jama-bandi, asal, khaali, wasool, or jilla?

Long before the English language imprinted itself on South Asia’s collective consciousness, there were other tongues that held that position of high esteem. Arabic, Persian and Urdu co-existed and were assimilated into Indian languages in a more intimate way. Interestingly, interactions with Arabs through trade and religious dissemination also led to the growth of hybrid languages such as ‘Lisan ul-Arwi’ or ‘Arabi-Tamil’ (also referred to as ‘Arabu-Tamil’) and ‘Arabi-Malayalam’ — with a canon of published literature and daily correspondence that supported a multicultural society up until the 19th century in southern India. Arabic-influenced vernacular can be seen in Sindhi, Gujarati, Arabu-Telugu and Arabu-Bengali too, to name just a few.

Maritime heritage and flower-shaped poems

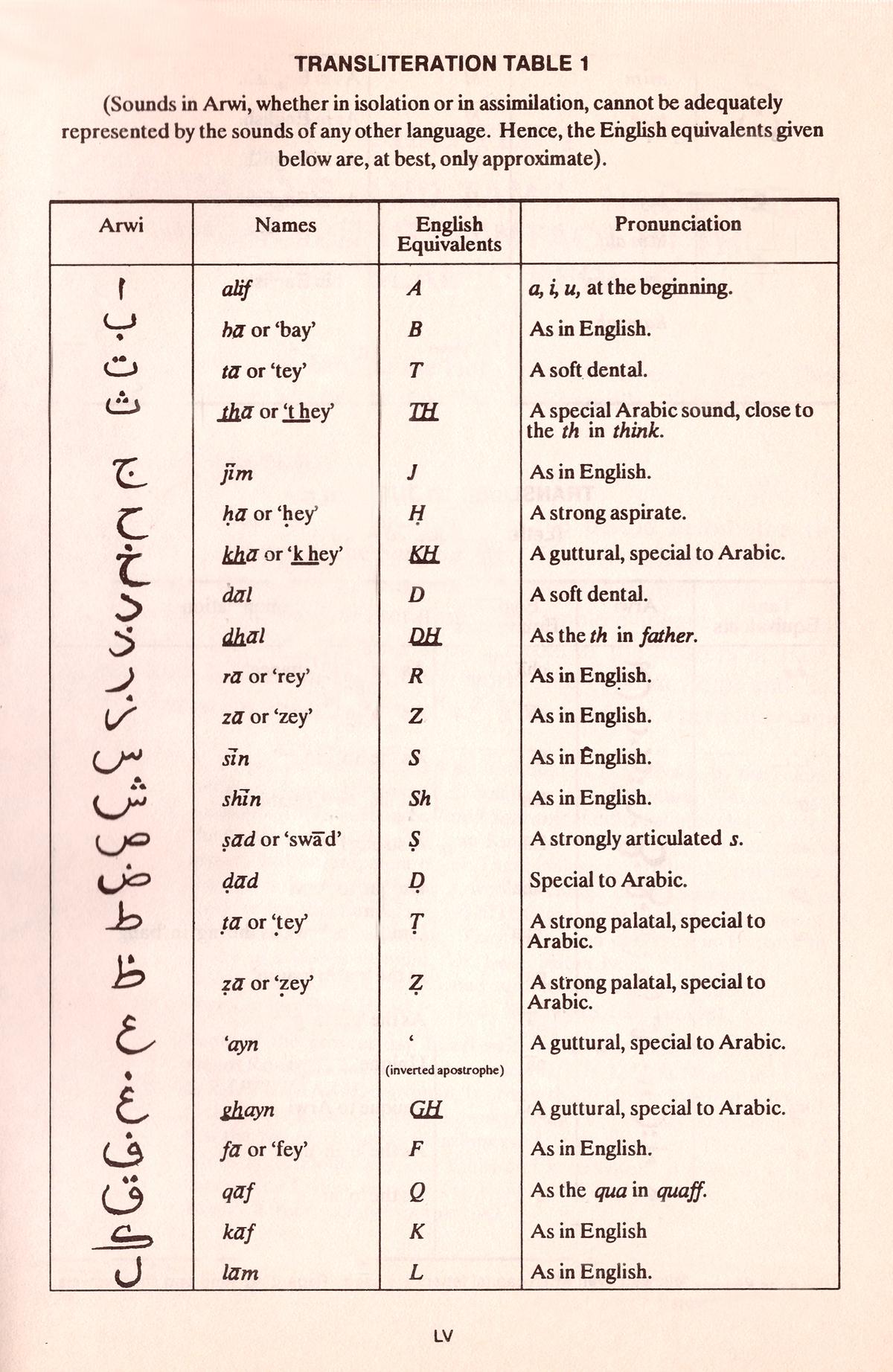

Arwi consists of 40 letters, of which 28 are from Arabic, and 12 are devised by adding diacritical marks that allow Arabic letters to express sounds particular to Tamil. Similarly, the Arabi-Malayalam alphabet has 56 letters.

In its heyday, publications in Arwi covered a wide range of subjects, including architecture, arithmetic, astronomy, fiction, horticulture, medicine, sports, sexology, war manuals, yoga and general literature. Madinattun-Nuhas (Copper Town, 1858), a historical novel in Arwi by Imamul Aras, published in 1858, is credited as being the first work of fiction produced by the Tamil-speaking people. And as scholar Tayka Shu’ayb Alim — the first Tamil Muslim to receive the National Award for Outstanding Arabic Scholar — notes in his book Arabic, Arwi and Persian in Sarandib and Tamil Nadu, Arwi Muslims wrote poems in the shapes of flowers, leaves and geometric figures, known as ‘Mushajjarah’ and ‘Mudawwarah.’ They were inspired by the ‘Nagabandanam’ and ‘Ashtabandanam’ genres of Tamil poetry, which were written in the shape of serpents.

A page from Arabic, Arwi and Persian in Sarandib and Tamil Nadu

Over time, these languages became the lingua franca for many Muslim settlements, and as recently as the 1950s, Arabu-Tamil was taught at home to girls and in Arabic colleges as an allied subject. Arabi-Tamil and Arabi-Malayalam played a key role in educating women from conservative Muslim families, at a time when they lived in seclusion.

Retracing a layered past

Publications in these languages have become rare today, and can only be found in libraries, seminaries and family collections — where, sadly, many of the owners do not know how to read them. Now, scholars have begun to scientifically document and preserve surviving literature.

Most recent among these efforts is a project for the British Library’s Endangered Archives Programme (EAP) titled ‘Mathematical Practices of the Indian Ocean World in Coastal Islamic Communities of the Coromandel and Malabar, South India’. It was executed by the Centre for Islamic Tamil Cultural Research (CITCR), affiliated to Jamal Mohamed College in Tiruchi, and in collaboration with Kerala’s Mahatma Gandhi University.

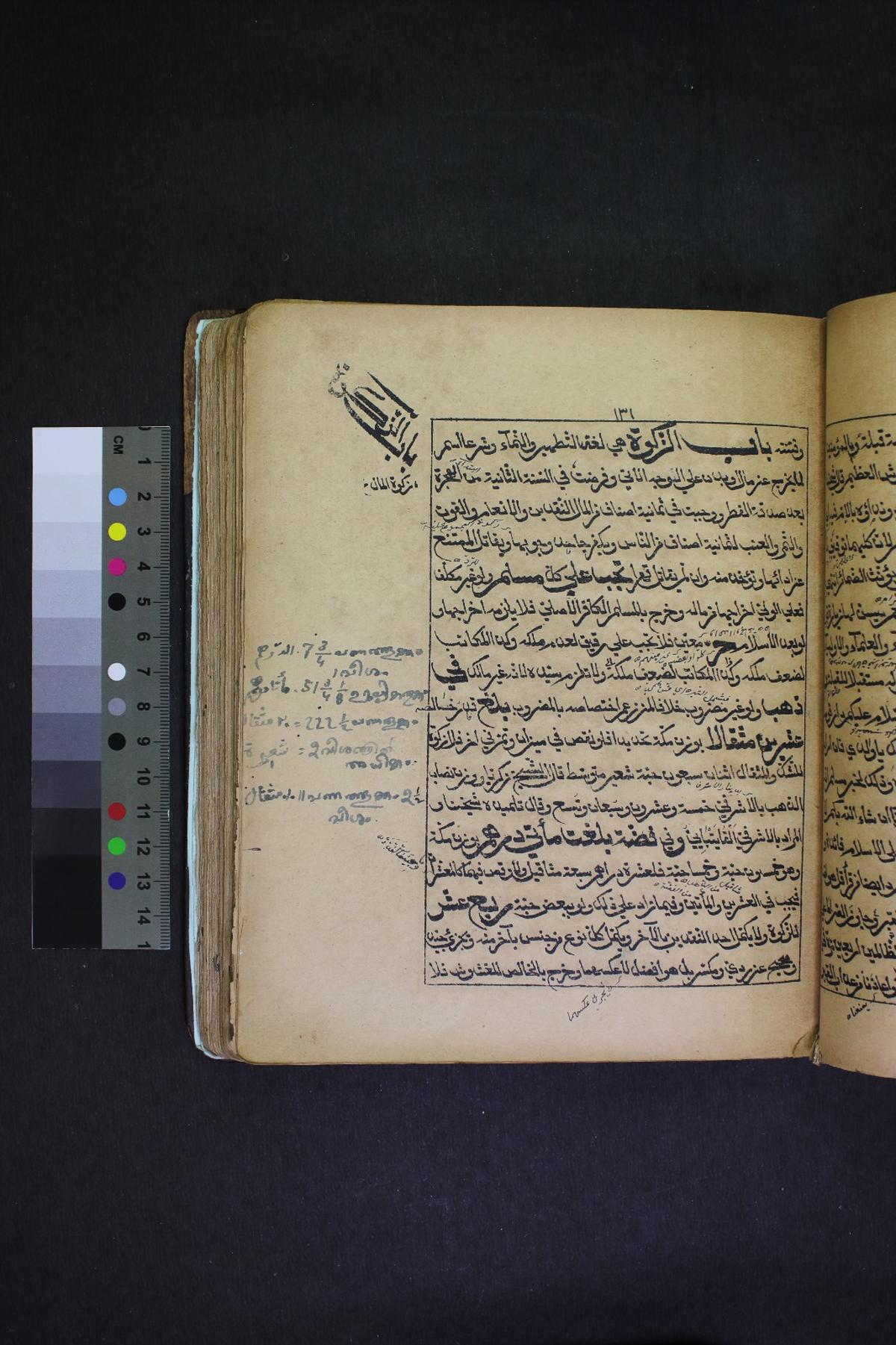

Text in Arabi-Malayalam

Supported by a grant of £14,926 (approximately ₹16 lakh), the year-long project surveyed and digitised notes, theological texts, printed manuals, marriage registers, publications and textbooks from the 18th century. The documents — sourced from personal collections, religious and social institutions, and Arabic college libraries in the states’ Coromandel and Malabar regions — focus on non-European learning and mathematical practices that are unique to the subcontinent. They are also a repository of ethnic medical knowledge, recorded in the form of songs for easy memorisation.

“You cannot write the history of a community with just stories,” says J. Raja Mohamed, director of CITCR and co-principal researcher of the EAP project (along with professor M.H. Ilias of Mahatma Gandhi University’s School of Gandhian Thought and Development Studies). “You need facts too, because these documents show how our ancestors lived.”

A book in Arabi-Tamil

Minutiae of the everyday

At a time when there’s a general lack of interest in record keeping and preservation in India, the project is a significant achievement.

Mohamed delved into the Coromandel region, while Ilias looked at Malabar, and their teams, with training from the French Institute of Pondicherry, the project’s archival partner, fanned out along the coastal towns. They retraced 62 printed books, 25 manuscripts, seven notebooks, six documents and four booklets in Arabi-Tamil and Arabi-Malayalam. The digitised versions — EAP 1457 — are available now on the British Library’s website.

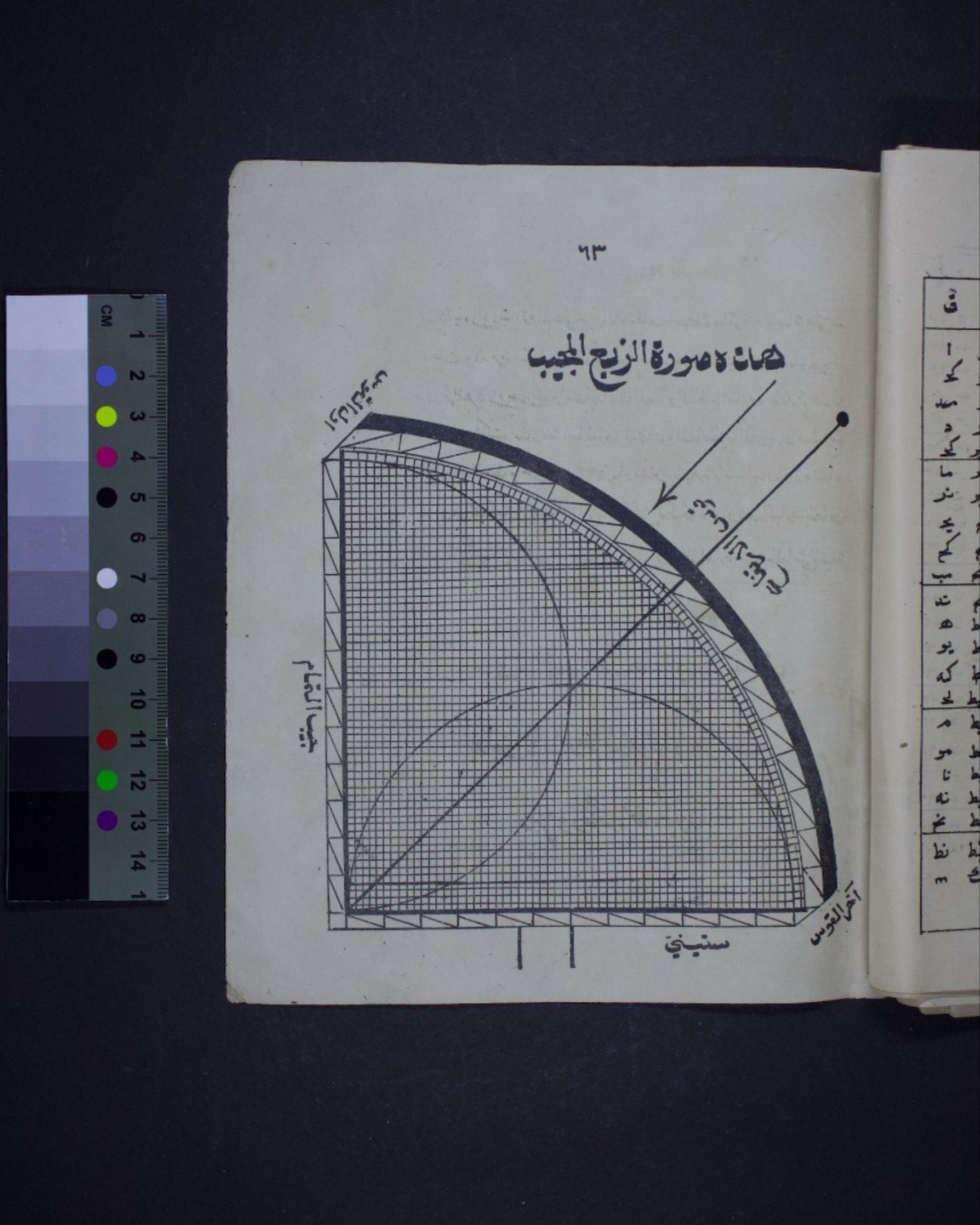

M.H. Ilias

“We found several texts detailing non-European ways of measuring and weighing. They were possibly brought to India by Arab travellers, scholars, and trade-based diaspora,” says Ilias, explaining how the project helped them learn more about the way Muslim communities in these coastal areas lived and worked. “It is an eye-opener to realise that activities like boatbuilding and mosque construction relied on these measurements, and are still in use in certain regions.” As examples, he cites ‘kullam’, which is still used to calculate liquid measures, and amshik, the five-stroke method of counting, prevalent in local markets. In Malabar, boatbuilding continues to use the calculation system of marakanakku (measure of wood).

Measurements in Arabi-Malayalam

The widespread usage of Arabi-Tamil, especially among Muslim women, could be seen, too. “We found various guidance booklets, and a collection of poems and folk songs on Islamic themes, indicating that the language was being taught to and read by Muslim women,” adds Raja.

Ilias remembers his grandmother being a prolific writer of Arabi-Malayalam poems. “Whenever she prepared Ayurvedic home cures, she would sing the Arabi-Malayalam recipes. Literacy in the language was a mark of prestige for Muslim women in Kerala, just as Arwi was for Tamil Muslim women,” he shares. “Sadly, when the Kerala government began its campaign for total literacy in 1990, my grandmother was assessed as ‘illiterate’ because she knew only Arabi-Malayalam.”

Quran in Tamil

There were some serendipitous finds too, such as a copy of the first volume of the Tamil translation of the Quran by A.K. Abdul Hameed Baqavi. Published in 1929 (volume 1) — its printing backed by the founders of Jamal Mohamed College in Tiruchi — the Tamil Islamic scholar’s effort, titled Tarjumat-ul-Quran bi Altaf-ilbayan (Translation of the Quran with a Glorious Exposition) was eventually completed in 1949, in a marathon effort that took two decades. “We had heard about the book, but this was the first time that we saw a physical copy and read the translator’s foreword, which gives details about the pioneering effort,” says Mohamed.

For Ilias and his team, the Malabar region also yielded several intriguing documents in Arabic, Malayalam, Arabi-Malayalam and Persian. “Our most interesting discoveries were the weighing and measuring techniques. They are still used extensively in Kerala, especially by the Mapilla Muslims,” says Ilias.

Hope for rare publications

Despite the wealth of documentation unearthed, the project also proved to be arduous. “Quite a few books, especially in the libraries of educational institutions, were disintegrating because they had been stored haphazardly in musty rooms,” says Mohamed.

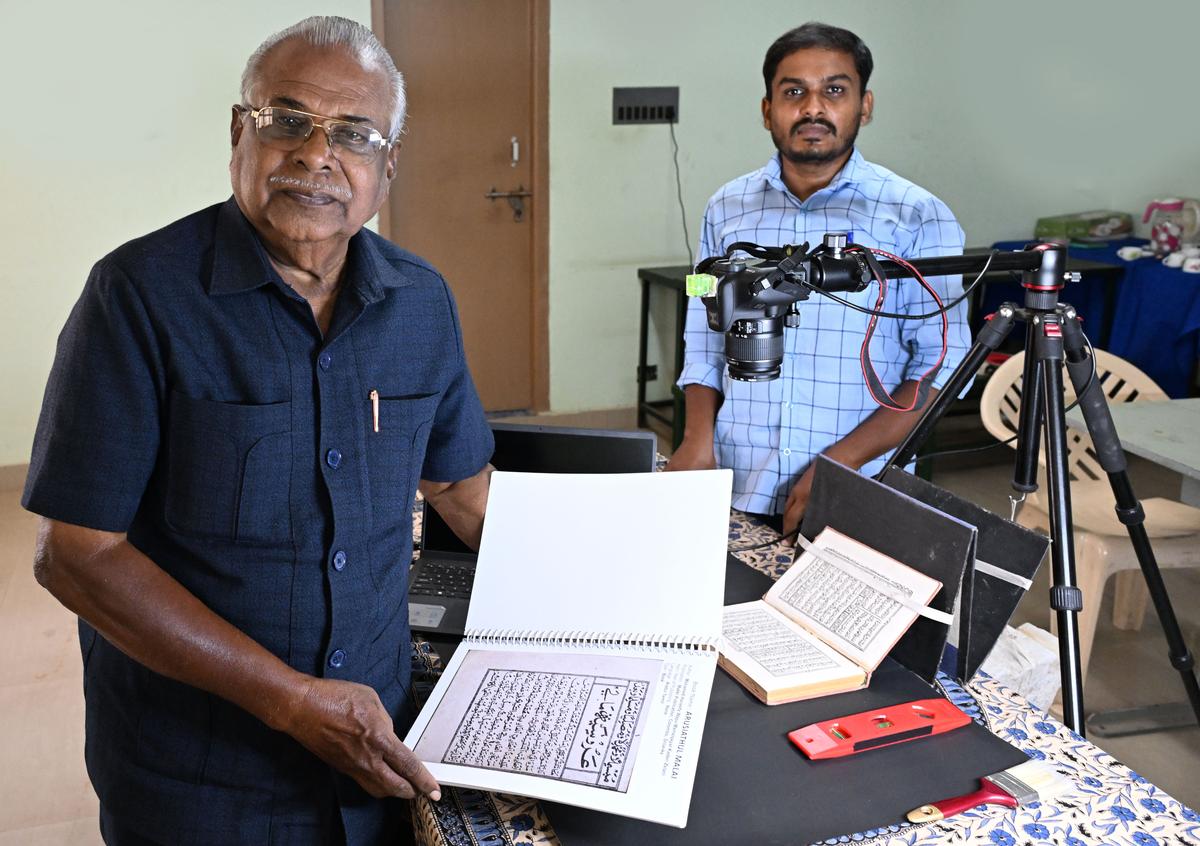

Raja Mohamed and his assistant working on the digitisation of Arabi-Tamil manuscripts

| Photo Credit:

M. Moorthy

In the case of personal collections, lack of knowledge about their own antecedents proved to be problematic. “Myths of origin and hearsay cannot be treated as historical fact, but that is what most people recounted. This is one of the reasons why it has become difficult to write an accurate history of Tamil Muslims today,” he adds. Some also developed cold feet, rescheduling viewing appointments umpteen times or flatly refusing to show their documents.

While similar problems were prevalent in the Malabar region too, Ilias is encouraged by initiatives to bring the outmoded Arabi-Malayalam into the modern era. “The University of Calicut’s C.H. Mohammed Koya Chair for Studies on Developing Societies has recently introduced a Unicode for Arabi-Malayalam that could help us recover more documents through computerisation. It gives us hope that rare publications in other dialects like Hebrew-Malayalam and Syriac-Malayalam will also get preserved eventually,” he concludes.

nahla.nainar@thehindu.co.in

Published – March 28, 2025 12:50 pm IST