DAG’s exhibition March to Freedom uses visual elements and lexical analysis to paint the socio-cultural and economic landscape of India through its colonial history

DAG’s exhibition March to Freedom uses visual elements and lexical analysis to paint the socio-cultural and economic landscape of India through its colonial history

The ongoing exhibition March to Freedom by Delhi Art Gallery (DAG) strides the dark corridors of colonialism to explore the idea of freedom. In doing so, it charts the evolution of India through visual elements and the lexical analysis of socio-cultural and economic landscape of the country as well as South-Asia. Though historian Mrinalini Venkateswaran curates the exhibition — a collection of prints, drawings, film posters, sculptures, paintings and figurines — with scrupulous attention to its narrative, she deliberately leaves its title open to the viewer’s interpretation. “Is it a statement of fact, an exhortation towards a goal within sight, or an idealistic aspiration? I leave you to decide,” she writes in the introductory note of the exhibition. Technically, the exhibition delves into all of the three contexts.

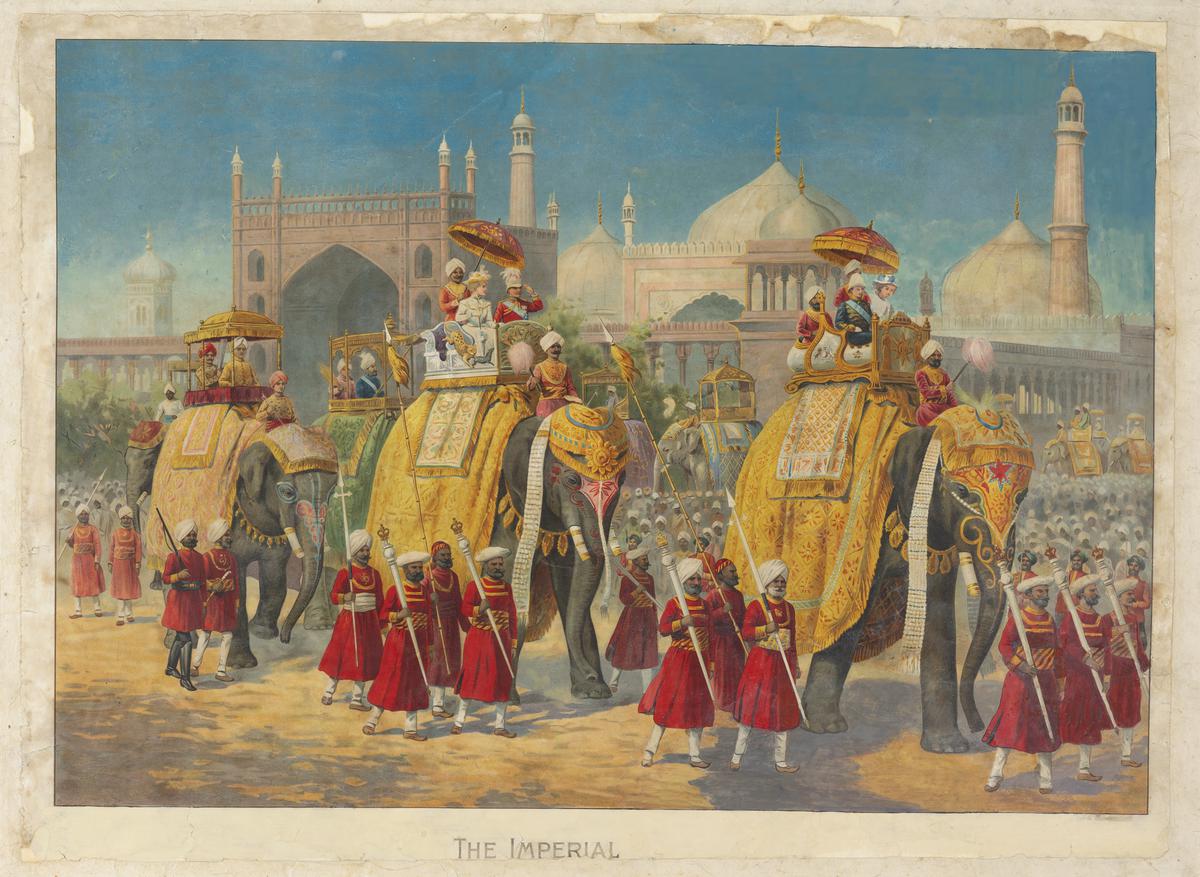

The visuals are structured around eight themes — The Battles for Freedom, The Traffic of Trade, See India, Reclaiming the Past, Exhibit India, From Colonial to National, Shaping the Nation and Independence — each of which is complemented by a corresponding essay. The first section engages with a series of conflicts, the most compelling of which is Thomas J Barker’s (engraved by Charles G Lewis) painting The Relief Of Lucknow & Triumphant Meeting of Havelock, Outram, Sir Colin Campbell, in November 1857. It commemorates the moment in 1857 when the siege of the British Residency at Lucknow by a section of mutinying Company soldiers was lifted. Swedish artist Egron Lundgren was in India during 1857, covering Lucknow ‘live’, through hundreds of quick sketches. Thomas Jones Barker used them to make the painting on which the print is based. While most prints in the section view India’s struggle with its colonisers through a European gaze, there are a couple of paintings by RK Kelkar and an unidentified artist that put the spotlight on Nanasaheb Peshwa and Mangal Singh Pandey. Accompanying the section is an essay by historian Maroona Murmu. She discusses the conflicts between colonial authorities and Adivasis, Dalits, and the tribes of the North-East, embedding them into the larger nationalist struggle and story.

Talking about the themes, Mrinalini shares, “I came up with the themes by going through the database of the DAG collections. I developed them keeping in mind the vast body of scholarship that exists on modern South Asian history. Although it is conceived to commemorate and celebrate the 75th anniversary of India’s independence, the exhibition is designed to do more.” The challenge, she says, was to create a coherent narrative that was not the same that most people might be familiar with through their history school books.

Charles Walters D’Oyly, Untitled, 1978

The second section, The Traffic of Trade, traces India’s trade relations with other countries through sea routes. The paintings and prints in this section also view the aspect of trade through the European lens, who paint maps, seascapes, portraits of Indian merchants, accountants and even their wives. Charles Walters D’Oyly’s painting of a boat laden with goods and people at the sea shore, might be an ordinary reflection of trade in those days, but it has an interesting connection with India’s art history. The artist was the nephew of Charles D’Oyly, a Company servant and artist based in Dhaka and Patna, who founded a local art society with like-minded friends and imported a lithographic press by sea all the way up the river to Patna so that they could make prints of their paintings. This section has two prints titled British Plenty and Scarcity in India by Henry Singleton which date back to the 1790s. The visuals are complemented by Professor of World History at the University of Cambridge Sujit Sivasundaram and Assistant Professor of History at Krea University, India, Aashique Ahmed Iqbal’s essays. While Sivasundaram demonstrates the links and overlaps between networks of trade, science and political thought, Iqbal tackles that quintessential Raj subject — the railways, in the third section See India.

NR Sardesai, Lahore Gate, Red Fort, Delhi, 1929

Ashish Anand, CEO and MD at DAG, says English artists in the 18th and 19th centuries tended to portray the buildings and landscapes they encountered as grand ruins, and empty of people. “They give the impression of an ancient and great India that was diminished by their time; available for the British and others to occupy. We know now (and Indian viewers knew then) that what we see here is not truly what was,” he adds.

The other five sections of the exhibition, garnished with essays by Lakshmi Subramanian, Pushkar Sohoni, Sumathi Ramaswamy and Aparna Vaidik, share the subsequent journey of India through its independence. The last section shows artwork by Chittaprosad, who produced his most seminal work in the crucial years preceding India’s independence. “DAG was fortunate to acquire his studio in 1999 even as Jyoti Basu, then the Chief Minister of West Bengal, wished to get it for the West Bengal Government.”

The section also shows Gandhi’s photographs clicked by French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson. “Many people around the world and in India, learned about Gandhiji’s assassination through the photographs of Henri, who was in India to take pictures of our newly independent country. He met Gandhiji and photographed him moments before he stepped out for his last prayer meeting on 30 January, 1948. And so he was there to take these images too, of a nation in shock and mourning at the killing of its ‘Father’. His pictures have power because they are intimate, and show us the personality of the people in them, or the mood around them,” says Ashish.

Calling it the only comprehensive collection of Henri’s photographs on Gandhi that exist in India, Ashish shares that “only after chasing the collections for years, we succeeded in acquiring them”.

Works are on display at Bikaner House, Delhi, till October 29.

.jpg)