[ad_1]

Veteran flautist Pt. Hari Prasad Chaurasia performing at the Sankat Mochan Sangeet Samaroh, in Varanasi on April 14, 2023.

| Photo Credit: ANI

A musical ode that was launched informally 100 years ago by a group of musician-friends has today become one of the biggest music festivals in North India. The venue is Sankat Mochan Hanuman temple in Benaras. Spread over six nights, the festival features nearly 60 concerts by artistes from different parts of the country.

Started in 1923, the festival is held every year in April coinciding with Hanuman Jayanthi. The 2023 edition marked the Centenary year of the festival, which has featured maestros including Pt. Jasraj, Girija Devi, Pt. Birju Maharaj, and Pt. Kelucharan Mahapatra in the past.

A lot has changed over the years. The non-ticketed festival, which began as a short performance became an all-evening celebration that got extended till 2 a.m. It subsequently turned into a two-night-long music festival, then three, and finally, a six-night-long affair. This year being special, it was a week-long event.

Though the concerts, referred to as haazri (offering), were earlier held right in front of Hanuman’s murti, they are now performed to the left of the Lord’s enclosure. To accommodate the crowd, screens are put up at various locations in and outside the temple. Parul (want her first name) Shah, an old Benaras resident, recalled how loudspeakers once let them enjoy the music from the comfort of their homes.

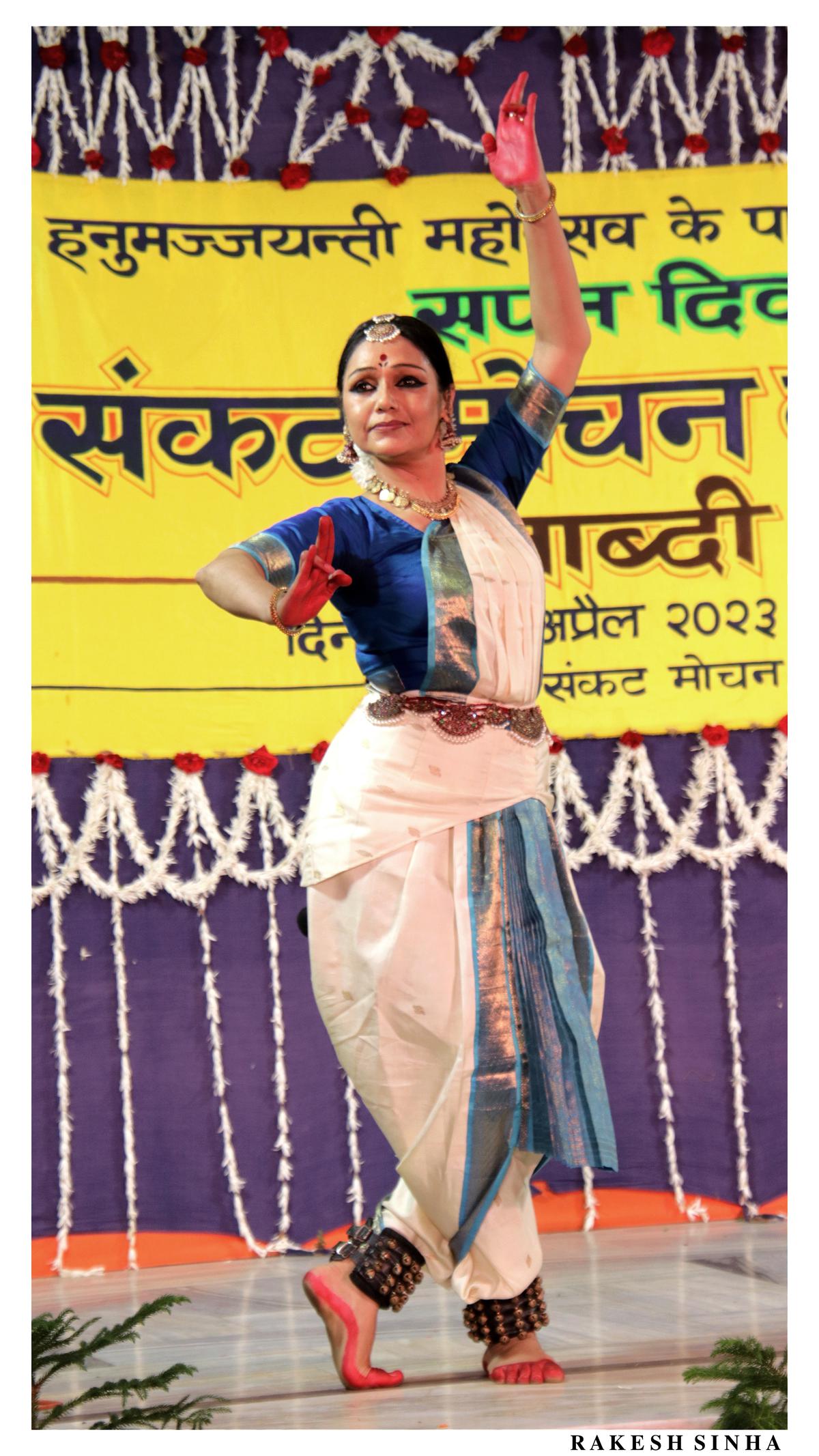

Senior Bharatanatyam dancer Rama Vaidyanathan performing at Sankat Mochan Sangeet Samaroh in 2023.

| Photo Credit:

Photo courtesy: Sankat Mochan Sangeet Samaroh

The festival, which earlier featured only male musicians, began including women performers in the late 1960s, when Kankana Bannerji, who lent vocal support to her guru, inadvertently became the first woman to perform here. A few years later, invitation was extended to women dancers too. The festival gradually evolved into an inclusive and multi-genre celebration with the inclusion of sufi artistes and Carnatic musicians.

A music festival dedicated to Hanuman

Sankat Mochan Sangeet Samaroh

Inaugurated in 1923

Held annually on the occasion of Hanuman jayanthi in April

Varanasi

The oldest performer at this year’s edition was the Benaras-based Pt. Rajeshwar Acharya, who had performed here as a 12-year old in the late 1950s. Talking about how the festival has been accommodating all kinds of music, he said, “even singing pop is not paap.”

Purbayan Chatterjee at the Sankat Mochan Sangeet Samaroh in 2023.

| Photo Credit:

Sankat Mochan Sangeet Samaroh

Thus, Punjabi pop singer Jasbir Jassi performed on the opening night, followed by ghazal singer Talat Aziz, bhajan exponent Anup Jalota, and playback singers Javed Ali and Sonu Nigam. Though these performances may draw youngsters, some rasikas felt slotting them between classical concerts affects the mood and spirit of the festival.

Playback singer Javed Ali performing at the Sankat Mochan Music Festival in Varanasi on Sunday, April 16.

| Photo Credit:

ANI

To perform in this setting is challenging for artistes, yet all of them anxiously wait to be invited. Conducted during summer, there are no fans. Since some portions are closed and some open, the audio output is not even. Also, the audience is seated too close. In addition, at around midnight and 4.30 a.m., the concerts are stopped midway for the rituals to be performed to the deity.

Pt. Sajan Mishra performs on the last day of ‘Sankat Mochan Sangeet Mahotsav’, in Varanasi, on April 17, 2023.

| Photo Credit:

PTI

Senior Bharatanatyam dancer Rama Vaidyanathan, who made her debut at the festival this year, felt that she could strike an instant rapport with the appreciative audience. For many music and dance aficionados, who come from across the country, it’s an annual pilgrimage. Uma Rajshekhar from Mysuru has been attending the festival since 1964. “I have many precious memories. I have heard several unique concerts here.” Ram Singh, an elderly rasika from Patna, said, “I don’t understand the musical intricacies, but just feel connected from within. The temple premises brings out clearly the spirituality in our music.”

According to Emmanuel Lebrun, director of the French Institute in New Delhi, who attended the festival, “the experience was incredible. For hours together, I stood and listened to the music being performed.”

Audience at Sonu Nigam’s performance at Sankat Mochan Sangeet Samaroh held in April 2023.

| Photo Credit:

Sankat Mochan Sangeet Samaroh

Sankat Mochan temple mahant, Vishwambhar Nath Mishra, a pakhawaj player, who is also the organiser of the festival, said, “This centenary year was the outcome of our hard work and desire to showcase our culture in all its diverse hues.”

[ad_2]

Source link