[ad_1]

Inside the koothambalam (temple theatre) at Vyloppilly Samskrithi Bhavan in Thiruvananthapuram, Marianna De Sanctis peers closely at an old film reel, using cleaning agents and tapes to return it to its old glory. Gathered in rapt attention around her are students ranging in age from the 20s to the 50s, the latest entrants into the emerging field of film restoration.

De Sanctis — who worked on restoring Malayalam auteur G. Aravindan’s classics Thampu (1978) and Kummatty (1979) — got into film restoration two decades ago because of her love of silent cinema. “A good part of the heritage of silent cinema was lost because it was printed on nitrate, which is quite fragile and decays over time,” says De Sanctis, who heads film repair at L’Immagine Ritrovata, a famed film restoration laboratory in Italy. “Our laboratory has around 70-80 people working in various aspects of restoration. Annually, we manage to restore around 80 films from all over the world.” At present, she is readying to restore avant-garde filmmaker John Abraham’s crowd-funded classic, Amma Ariyan (1986).

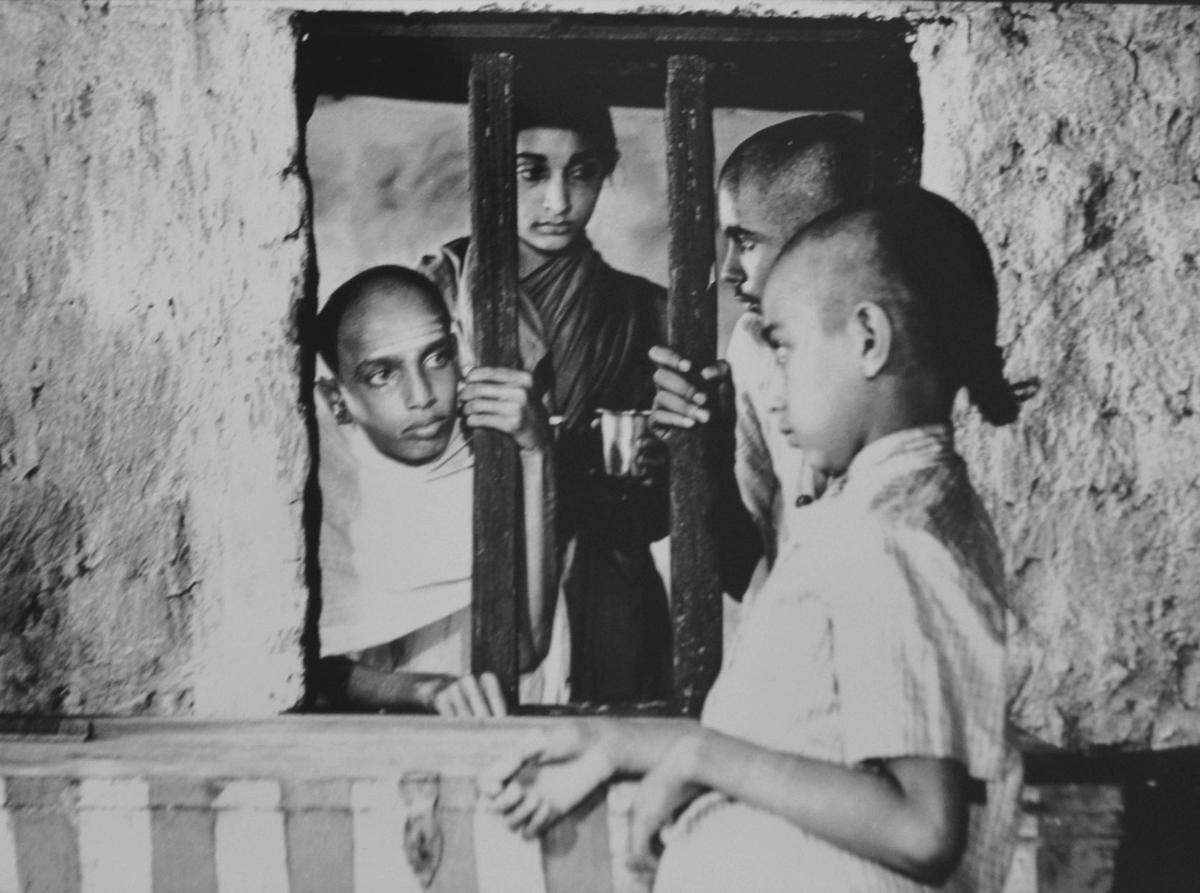

A still from Amma Ariyan

De Sanctis was one of many experts from countries such as the U.S., the U.K., France and Portugal, who was part of the Film Heritage Foundation’s (FHF) Film Preservation & Restoration Workshop India 2024. Organised earlier this month, the travelling workshop’s ninth edition also happens to be its last. In 2025, the foundation is set to open the Centre of the Moving Image in Mumbai, which will house an archive, research centre, and a year-round training facility.

At the Film Preservation & Restoration Workshop India 2024

| Photo Credit:

C.R. Narayanan

Repair, restore, repeat

This year witnessed a flurry of re-releases of mainstream hits from recent decades running to full-houses. Restored titles from regional languages, however, often don’t attract as much notice. But the FHF has quietly gone about its work of creating public interest in the art of film preservation and training a new generation of technicians. For the past decade or so, it has been relentlessly tracking down the last remaining prints of some of the best independent cinema India has produced, and painstakingly restoring them, frame by frame. Some of its important restoration works such as Thampu and Shyam Benegal’s Manthan (1976) even had their premieres at Cannes over the years.

A still from Thampu

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

The week-long workshop included lectures and hands-on sessions on film, video, audio and digital preservation, film conservation and restoration, digitisation, disaster recovery, cataloguing, and more. And many of the participants came with specific plans. C.P. Thushara from the National Film Corporation of Sri Lanka attended with fellow technicians to understand the cutting-edge technologies of preservation. Their presence is part of the France-India-Sri Lanka Cine Heritage initiative spearheaded by the FHF and the French embassy. Back home, the technicians will start restoring the classic Sinhala film Gehenu Lamai (1978) by Sumitra Peries.

Etienne Marchand from the Institut National de l’Audiovisuel

| Photo Credit:

C.R. Narayanan

Huzaifa, 52, a faculty of videography and caretaker of the archive at the Aljamea-tus-Saifiyah in Surat, Gujarat, came down to learn how to save the institution’s old materials. “Our university is 200 years old. It has a vast collection of educational films, photographs and audio dating back decades. We are trying to learn methods to preserve these as well as to restore things that were thought to be lost,” he says.

Another group from the Kerala State Chalachitra Academy, which has recently begun restoring Malayalam classics, was there to fine-tune their understanding of preservation. Recently, the academy recovered prints of over 100 films from the state’s public relations department office, where they were stored after being sent for consideration for the Kerala State Film Awards. The titles included P.N. Menon’s Olavum Theeravum (1970), Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s Vidheyan (1994) and K.G. George’s Yavanika (1982).

A still from Vidheyan

Rewinding the classics

It is apt that the travelling school made its final stop in Thiruvananthapuram, the city of P.K. Nair, the pioneer of archiving in India, and the man who founded the National Film Archive of India (NFAI) in 1964. Incidentally, Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, who founded the FHF in 2014, began his journey in film preservation by making Celluloid Man, a moving documentary on his mentor Nair’s efforts to preserve India’s cinematic heritage.

“Over the past decade, we have managed to train over 400 people in the art of film restoration and preservation,” says Dungarpur, who is also the festival director of the MAMI Mumbai Film Festival. “We have helped set up archives in Sri Lanka, Nepal, Manipur, and Odisha, and several small ones in the country. But a lot of work still has to be done as 95% of our cinematic heritage is in danger.” At MAMI last month, the foundation’s restorations of Girish Kasaravalli’s Ghatashraddha (Kannada, 1977) and Odia film Maya Miriga, directed by Nirad N. Mohapatra, were screened. Dungarpur plans to have more on the roster in the next edition. Next month, the Kolkata International Film Festival will screen five restored films: Manthan, Ghatashraddha, Maya Miriga, Thampu and Manipuri film Ishanou, directed by Aribam Syam Sharma.

A still from Ghatashraddha

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy the Information Department

Restoring a single film might take months or years, depending on the quality of the available print. While the restoration of Thampu took two years, the work for Maya Miriga stretched over three years. The cost of restoration can range anywhere from ₹35 lakh to ₹50 lakh, and sometimes even more.

A still from Maya Miriga

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Film Heritage Foundation

“Compared to the West, we started our restoration journey 50 years later. Almost every global institution in this field works with government support. However, that is not the case in India,” says Dungarpur. “One of our major goals is to restore films from different parts of the country, rather than just focusing on Bollywood.” And if the full houses at the screenings of restored classics are anything to go by, there is an audience for these forgotten gems.

Published – November 21, 2024 12:21 pm IST

[ad_2]

Source link