[ad_1]

In the years gone by, the fountain at the Fawwara intersection in Chandni Chowk seldom worked. Yet, few complained. Most people came to Fawwara for their daily news, for here sat a newspaper seller who sold practically every language newspaper in the country.

Besides English, Hindi and Urdu dailies, one could get Punjabi, Marathi and Bengali papers too. He did not sell many magazines, the sole exception being Shama, the Urdu monthly that presented a heady cocktail of Urdu literature, Indian culture and Hindi cinema. Shama, like water, charted its own course.

Founded by Yusuf Dehlvi in 1939, some bought Shama to read Urdu writers. The who’s who of Urdu litterateurs, including Rajinder Singh Bedi, Sahir Ludhianvi, Saadat Hasan Manto, Ismat Chughtai and Qurratulain Hyder, graced its pages. There were pieces by connoisseurs of Indian culture as well, talking of traditions, little and large, and values, shifting or timeless.

Shama was appreciated in literary circles at a time when Delhi had a lively literary circuit with its mushairas, book readings, debates and even street theatre. Yet it would have remained a niche publication but for a couple of masterstrokes by Yusuf Dehlvi’s sons – the widely read Yunus Dehlvi and the widely popular Idrees Dehlvi – who turned what was otherwise a haloed literary publication into a family magazine.

Literary love 1960 cover of Shama and editor of the Urdu magazine

| Photo Credit: Special Arrangement

Idrees had strong film connections. In a column he wrote under the pen name of Musafir, he talked of little things in the life of film stars: the films they signed, the films they opted out of, the flops they gave or the jubilee hits they notched up. He talked too of their relationships, their moments of stolen pleasure. He backed it all up with photographs of film shooting, movie storylines and lyrics of popular songs.

Readers lapped it up. Within no time, fans of Meena Kumari and Madhubala, Sadhana and Sharmila Tagore, Sridevi and Jayaprada started collecting the photos of their matinee idols.

Emboldened by the success, Shama started its own annual film awards with a graceful function at Ashok hotel’s convention hall. Soon, the biggest stars of Hindi cinema started frequenting Shama Kothi on Sardar Patel Marg in New Delhi, the residence of the Dehlvis named after the magazine. From Dilip Kumar and Sunil Dutt to Dev Anand, Rajendra Kumar, Rajesh Khanna and Dharmendra, they would all come over.

The rise and fall of Shama Shashi Kapoor and Sadia Dehlvi

| Photo Credit: Special Arrangement

Once, as Vaseem Dehlavi, son of Yunus, recalls, “Sunil Dutt and Sanjay came shortly after Nargis Dutt had passed away to share their sorrow.” Often, the staff photographer of Shama clicked the pictures of stars here. They were then shared with readers as exclusive photos.

From predominantly abstract illustrations and photographs in the 40s, Shama by the 60s started having film stars on the cover. There were also film quizzes where a hundred cassettes of a new film’s songs were given away as prizes in the 70s and 80s. Every issue sold at least a lakh copies. People went to newspaper stalls to pick up their copy if their vendor delayed in delivering it at their house.

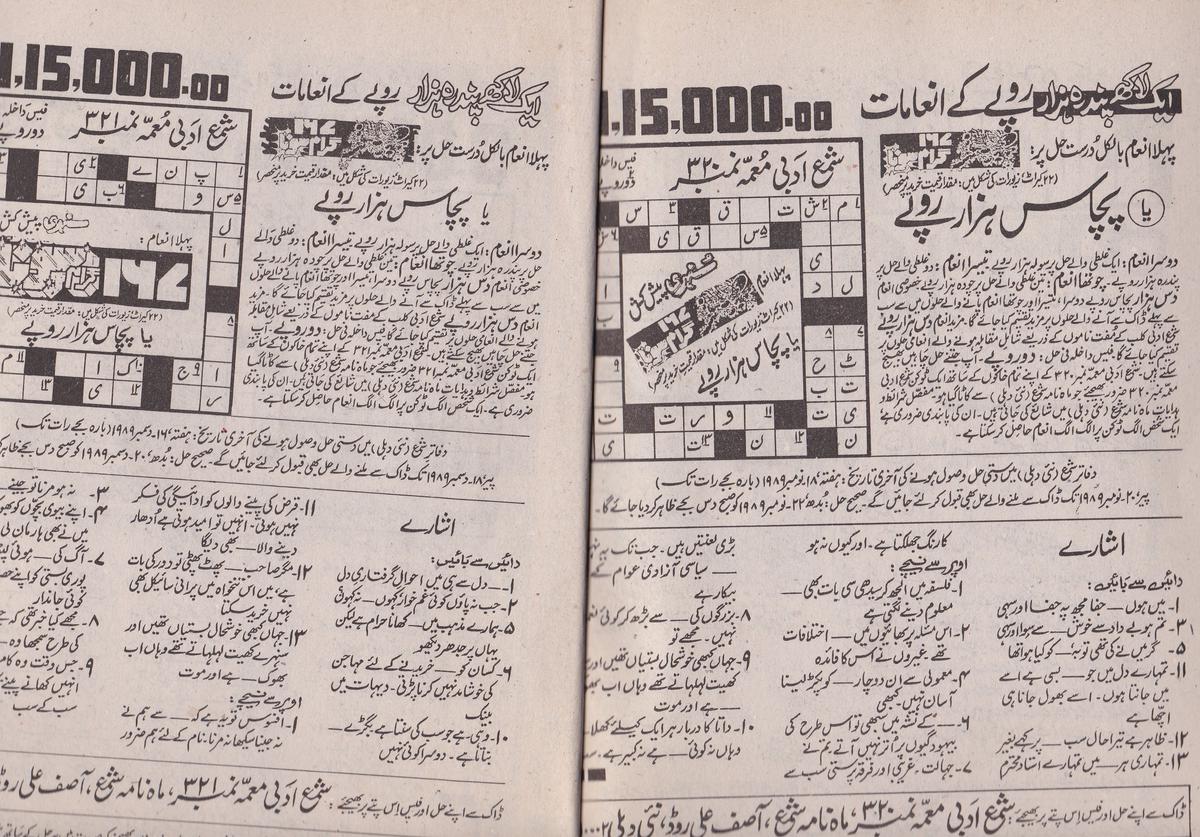

Crossword craze

The other big push was given by Yunus Dehlvi who had joined his father at the magazine as a young boy of 14-15. He started an Adabi Muamma (loosely culture crossword). It was in many ways the first such venture in an Urdu magazine. Men with pretensions to knowledge of varied kind were so hooked to Adabi Muamma that the magazine started getting lakhs of replies to every crossword. They all vied to win the two kilogram of gold bumper prize every month in the 80s.

As Vaseem Dehlavi reveals, “It was a completely honest exercise. When my father started putting the muamma together, he would lock himself in a room for two days and not allow any family member to come in.”

The rise and fall of Shama The magazine crossword

| Photo Credit: Special Arrangement

The newspaper sellers matched its huge popularity with their innovation. They started selling forms for the puzzle and photostat copies of the original crossword separately. There was a time in the 70s and 80s when the magazine’s cover price was ₹5 but the photocopies of the muamma were sold separately by some vendors for ₹10!

There was a pickle seller in Old Delhi who made hay while Shama shined. He started selling the muamma, besides his pickle delicacies. Then there was a bookseller at Nai Sarak who mixed books with the puzzle. Children came for books, their parents for the puzzle. “We used to get at least 2 lakh responses to each muamma. If more than one person got the answer right, the prize money was shared between them. If in some issue, nobody got the right answer, it was carried over to the next issue. The prize money for the following month was added to it. There was that level of integrity to the whole issue,” says Vaseem Dehlavi, who is now based in Mumbai.

All good things, however, do come to an end. By the 90s, Urdu was no longer as popular a language. And the internet provided access to films. The heady days of longing for photographs and interviews of film stars are consigned to history. Add to that the crests and troughs of the family business. By December 1999, Shama, meaning candle flame, was extinguished, leaving many a parvana (moth) with happy memories of the years gone by.

[ad_2]

Source link