[ad_1]

The diary is dog-eared and gravy-stained, fraying at the edges, its pages sepia. The old grandfather clock in the foyer stands sentinel over the Burma teak staircase that creaks with the weight of history.

A page from Umayal Palaniappan’s diary

| Photo Credit:

R RAVINDRAN

Umayal Palaniappan leafs through the diary, strangely yearless, drawing attention to the recipes written in a neat hand, in a mix of English and Tamil, and the kolams particular to a festival. More pages spell out the paayasam varieties, the names of utensils peculiar to the Chettiar kitchen and the essential items such as manjal koththu and thundu used to decorate cows during Pongal. The diary, for Umayal, has been a ready reckoner of all things Nagarathar, ever since she came to this British-era house as a young bride.

Umayal Palaniappan, author of The Nagarathar Way, at home in Chennai

| Photo Credit:

R RAVINDRAN

“My mother-in-law was a disciplinarian. One of the few women who drove a car in the 1960s, she asked me to write down everything she dictated on how to keep the community’s way of life alive,” says Umayal, 60. Over the years, Umayal, currently vice president of the Spastics Society of Tamil Nadu, became deeply involved in preserving the Nagarathar way of life.

A photograph from the book

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

Also known as the Nattukottai Chettiars, the community lived along the coast trading in salt and gems during the Sangam age. They moved to the Tamil hinterland after a tsunami centuries ago, living in a cluster of villages that offers little by way of natural beauty other than scattered palms and dry weather. With the advent of colonialism, the Nagarathars became successful money lenders and prospered far from Indian shores — in Burma, Malaya, Singapore and Vietnam — but they always returned to live in the country they called home. Here, they poured their new-found wealth into their Palladian and Art-Deco-inspired houses, illuminating them with rose embossed tiles from Birmingham, chandeliers from Murano, teak pillars from Burma and etched mirrors from Belgium. They also invested heavily in philanthropy, founding schools and colleges and funding charitable organisations.

With the fall of South-East Asia to the invading Japanese during the Second World War, the Chettinad expatriate dream was largely extinguished. Burmese nationalism, insurgencies in Malaya, war in Indo-China and socialism in Ceylon further eroded the economic foundations of this affluent community. And the mansions that once stood as proud markers of wealth turned silent outposts to be discovered only by travellers who had steered off course.

A photograph from the book

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

“When the younger generation of the community migrated to the West, the old ways of life slowly disappeared. When my nephew got married, my mother, sisters and I thought it would be a good idea to gift a book on Nagarathar culture as a take-away. So, we had it written out in Tamil. Then someone suggested an English book would have a wider reach. So we translated and embellished it with photographs,” says Umayal.

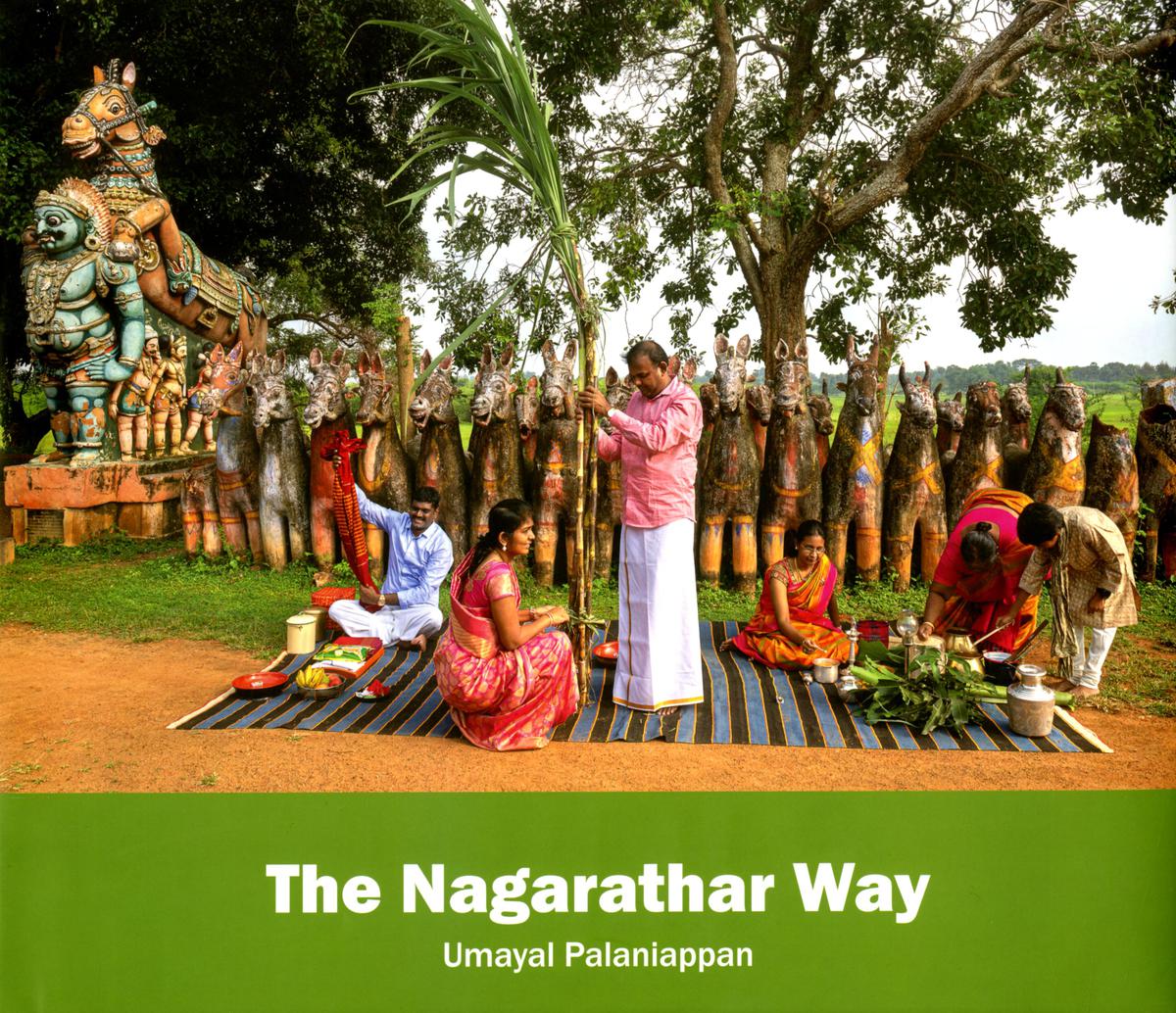

The book jacket

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

The Nagarathar Way authored by Umayal and a team effort of “my siblings and their families, in-laws, friends and others from the community” is a 200-page coffee table book on the rituals, customs and cuisine of the community. It follows the chronology of festivals in the Tamil calendar, beginning with the new year, and how the Nagarathars celebrate them. It throws the spotlight on celebrations that have faded from memory such as Aavani Gnayiru Pongal and Aippasi Mudhal Muzhukku. It highlights the rich kolams that decorated their hearths and sumptuous dishes that were served on banana leaves. Ilandosai and kalkandu vadai recipes jostle for space with thattapayiru maanga kuzhambu. Towards the end, the book dedicates a couple of pages to the Nagarathar lingo, and their unusual way of addressing close relations.

A photograph from the book showcasing sweets and savouries prepared for a newly married couple’s first Deepavali

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

“The recipes were never written down but sourced from various families. The standardisation and trials took a while,” says Umayal adding that work on the book began in 2019, and help and guidance came from her niece Valli Vairavan, language experts, professors, doctoral papers and other books on the community.

Despite the pandemic intervening, photographers Clare Arni and Selvaprakash Lakshmanan travelled to Chettinad to capture moments in a Nagarathar’s life with both incredible beauty and clarity.

Shot in old mansions with mold swirling like eddying pools on parapets, and jewel-like tones lighting the interiors, the photographs are peopled by members of the family who ‘participate’ in the various festival celebrations. Decked in traditional finery — checked saris and diamond chokers, gold bordered dhotis and turbans, drawing kolams, pulverising masalas, and blowing the auspicious conch — they create stunning portraits of a way of life that Umayal hopes more people will follow.

“The Nagarathars have held on to tradition even when they lived abroad. As more of them return to their roots I hope the book helps them navigate the way.”

The Nagarathar Way is priced at ₹1,800 and is available at Amethyst, Whites Road and Manjal store, MRC Nagar, Chennai. For details, call 7200199318.

[ad_2]

Source link