The Elephant Whisperers, a heart-warming story of a couple Bomman and Bellie, and their unbreakable bond with Raghu, an orphaned elephant, has been nominated in the ‘Documentary Short Film Category’ in the 95th Academy Awards. Filmed in Tamil Nadu’s Theppakadu Elephant Camp at the Mudumalai Tiger Reserve, Kartiki Gonsalves’ documentary shines light on the bond humans and animals can share, but also notes the growing man-conflict in the elephant corridors of the Western Ghats.

Many films made from the region have turned the spotlight on indigenous tribes, the unsung heroes. Malasar, a six-minute conservation film, narrated by actor Nasser, available on YouTube shows not just the sacred bond between elephants and the Malasar tribes of the Anamalai Hills but also the need to protect the tribe’s identity and conventional wisdom. Nasser’s calming, emotion-packed voice speaks for 51-year-old Mani, the caretaker of Kaleem, a 53-year-old elephant. Mani calls Kaleem his older brother and says, “There’s no path we have not trodden in this forest. My ancestors and their elephants have roamed the forests and created the path for us. We blindly follow.”

The Elephant Whisperers

| Photo Credit:

BHUVAN

“While Kartiki’s film brings out the beautiful bond that the caretakers share with elephants, like their own children, Malasar showcases hidden stories and unsung heroes, the Malasar tribes who give their youth and an entire lifetime caring for the animals,” says Supriya Sahu, additional chief secretary, Environment, Climate Change and Forests Department adding that in a gloomy world where pollution is rampant, people are turning less tolerant towards animals and wildlife, and several wildlife species becoming endangered, such heart warming stories give hope that all is not lost. “It puts caretakers as beacons of hope and that’s why such films are important. These are true life stories that are inspirational. Elephants live with caretakers like their children. It shows how a beautiful bonds can exist between humans and wild beings. “

In Tamil Nadu, a pioneer in rehabilitation and maintenance of captive elephants, over 60 elephants are cared for by mahouts (elephant trainers) and cavadies (assistants) at Theppakadu in Mudumalai Tiger Reserve (MTR) and Kozhikamuthy at the Anamalai Tiger Reserve (ATR), some of the oldest elephant camps in the country. The mahouts are drawn mostly from local tribal communities like Malasars and Irulas. The maintenance of camps and training of elephants is done as per the traditional knowledge of tribes. Recently, the Tamil Nadu Government sent 13 mahouts from the camps for training at the Thai Elephant Conservation Centre in Thailand. “It’s a first and we plan to send more in batches to Sri Lanka or similar places. It’s time to recognise their service and build their capacities. The caretakers are the real heroes that the world needs to know and appreciate the sacrifices they make. The younger generation should value their service and respect the mahouts who give everything for wildlife. ,” adds Supriya Sahu.

It’s the mahouts and cavadis who form the backbone of captive elephant care. Says I Anwardeen, Principal Chief Conservator of Forests, based in Chennai, “The tribals gained traditional wisdom of elephant behaviour, a combination of science and compassion, over a period of time. It is important to use this wisdom, handed down over generations, in taking care of the elephants. While dealing with orphaned elephant calves or conflict elephants, human intervention is the key.”

Malasars use as many as 60 commands and the elephants respond to it, but beyond that they share an intricate bond, says MG Ganesan, a forest officer who worked in the ATR. The captive elephants help mitigate man-animal conflict. For example, Kaleem, a kumki (trained elephant) has helped capture more than 25 wild elephants in Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and Kerala over the past 20 years. “Along with the kumkis, we have done several field operations like patrolling, weed removing, and elephant capture. About eight years ago, when a wild elephant ran amuck in the Chhattisgarh forests, it was a Malasar mahout from Anamalai who disciplined it in just two days. They just use a cane as shown in The Elephant Whisperers. Malasars are the best in rescue and rehabilitation of elephants. After seeing videos of Kaleem and his caretaker Mani on YouTube, tourists now don’t stop with clicking selfies, they interact with the caretakers and want to know more.”

These films put the native indigenous tribes in limelight, bring an emotional connect, and clear myths surrounding captivity, says Pravin Shanmughanandan, editor of Pollachi Papyrus, who made Malasar. “Their conventional wisdom is irreplaceable. They take care of the largest mammal on earth, day in and out, and it requires a lifetime of dedication. Such films have opened doors for people to understand elephants in captivity.”

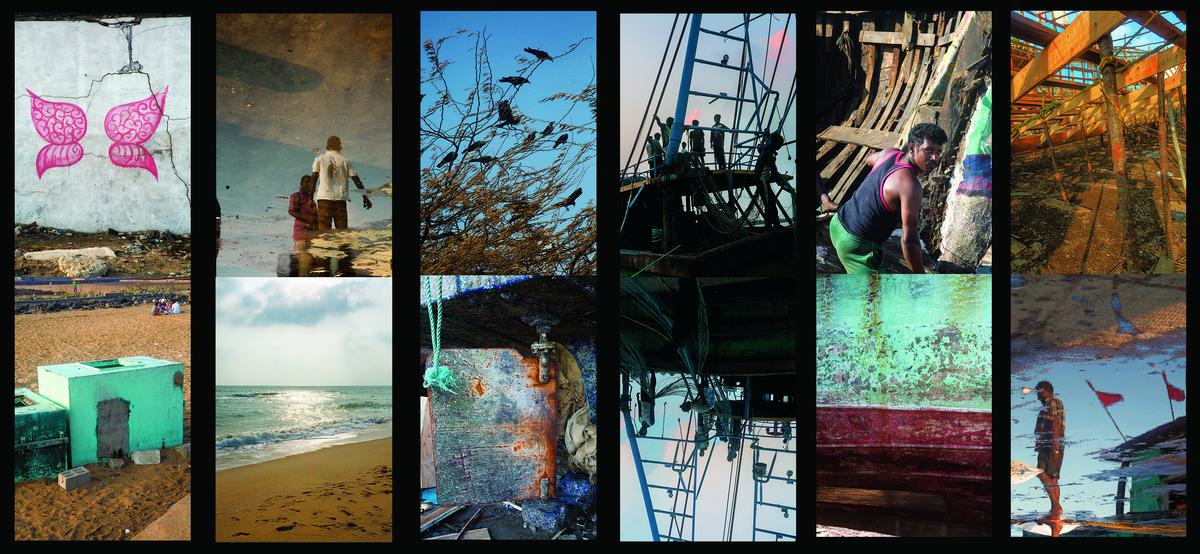

A still from Kaliru

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

“A visual film enhances the message on conservation and the reach is immense,” says Jeswin Kingsly whose 18-minute film, Kaliru (bull elephant) released in YouTube won 12 international awards in January 2022, with a notable Nature in Focus award in India and a nomination at Jackson Wild internationally. Jeswin, a naturalist based in Mettupalayam who is currently working at Tadoba Tiger Reserve in Maharashtra, says the film narrated by renowned wildlife photographer and conservationist Belinda Wright addresses human-animal interactions at conflict zones like Mettupalayam, Valparai and Dhimbam forest and also the role of communities in conservation.

Says Anwardeen, “Elephants have an intense emotional intelligence, and social life. We always see them from an utilitarian and ethical point of view, when the films showcase their beauty, behaviour and the entire spectrum, it motivates humans to appreciate, value, and protect the species. Once they fall in love with elephants, they start looking at forests as a habitat of the wild. Eventually, they turn conservationists.”

.jpeg)