[ad_1]

May in Ayemenem is a hot, brooding month. The days are long and humid. The river shrinks and black crows gorge on bright mangoes in still, dust green trees. Red bananas ripen. Jackfruits burst. Dissolute bluebottles hum vacuously in fruity air. Then they stun themselves against clear windowpanes and die, flatly baffled in the sun.

— The God of Small Things (1997); Arundhati Roy

May is a hot, brooding month all over Kerala, the days are long and humid. We’d already be five or six weeks into our summer holidays by the time May came along, and as the air swelled, we’d walk around, our limbs heavy and our minds dulled, boredom a physical weight sitting on top of our heads. For a while there, even the idea of going back to school held promise. But then, someone would think of something to do, an adventure to embark on or some mischief to make, and off we’d go again.

Children underneath a mango tree at a village near Thrissur

| Photo Credit:

MUSTAFAH KK

Growing up in the 1980s, summer holidays did not arrive with the promise of visiting a new destination, seeing the sights or learning about a new culture. My family was not big on holidays, there was no money. And so for the couple of thousand kids in the township I grew up in, as well as for the millions of middle class kids in pre-liberalised India, summer holidays meant being left to our own devices to find whatever entertainment we could. There was no television other than droll Doordarshan with its Krishi Darshans and Sarangi Vadans, and going to the movies was a rare occasion. Needless to say, there were no mobile phones or the internet or, in our case, even rudimentary video games. Time took on an elastic quality, stretching endlessly or snapping swiftly, depending on what we were up to. What should we do, what should we do, we asked each other endlessly.

Off to the grandparents

School closed mid-March, the last examination done and dusted by lunch on Friday. We had a couple of weeks to finish everything we had planned and postponed until the holidays, swimming in the club or going fishing in the bund. And then early April, we’d pack our bags and board a train with our mother to Palakkad. At Thrissur station, she’d buy us medu vada, or if it was the afternoon train, banana fritters wrapped in a leaf, the oil leaking into our hands and glistening around our lips. We’d spend a few days at our aunt’s, playing with our elder cousins, two girls who weren’t encouraged to play very much. Then we’d board a bus and go to our grandparents’, a rambling two-storeyed mansion in a village. My mother would spend a few days and go back, leaving us there for another fortnight. There were even fewer fun things to do in our grandparents’ home than our own, and the kind of entertainment our grandmother offered was assigning us the duty of chasing the crows away from the rice or tamarind or whatever she was drying in the sun that year. We’d sit there wilting in the shadow of the verandah, listlessly swinging a black flag.

The author as a young girl.

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

For the rest of the time, my brother and I devised our own projects. One favourite activity, born out of a boredom so intense you’d think you were losing your mind, was drawing water from the well, the rope cutting through our soft palms, while the bucket swung and rose. Then we’d drain the water back into the well and try again. At some point in this exercise one year, a silver glass that we used to drink water from, fell into the well. My grandmother was not the kind to hold you close and whisper that it was okay. She let us have it, not just for the day but for the rest of her life, the fallen glass always came up, first as admonishment and later as nostalgia. The glass lay there glinting in the sun until the following year, when my grandmother got the local handyman, who was also the village drunk, to jump into the well and rescue it. This provided us with a week of entertainment, as my grandmother assessed the drunk’s sobriety and cleanliness to allow him into the well. He failed on multiple occasions until finally, with a defeated sigh and a look of death towards us, she allowed him in, yelling instructions at him and curses at us. No matter how angry we made her, eventually around April 14, when the festival of Vishu came around, she’d soften, waking us up at 4 am, her hands covering our eyes as she walked us one after the other and made us sit in the room, where she’d have assembled everything yellow: a mango and some cassia flowers, a heap of rice, some gold coins, a bronze lit lamp, and she made us look first at ourselves in the mirror, and then at this bounty of golden hue and wished for us a year of peace and prosperity. Then my grandfather gave us our Vishu money – ₹11 per grandchild – and after a quick drink of Bournvita, we were handed over access to a giant box of firecrackers that we’d work our way through over the next few days. Family love, I realised then, was a subtle presence, you’ll only find it if you look for it.

Nature’s way

When we were a little older, probably nine and ten, our neighbour from the township, a childless couple who loved us immensely, moved to their village home. For a few years, we were sent there for a week during the summer holidays, a house where there were no rules and you could eat breakfast for dinner. We swam in the pond by the side of the house, water snakes gliding around us, and kingfishers ducking in economically, and often emerging with silvery fish writhing in their beaks. In the evenings, we lay on the cemented courtyard, the humid air heavy on our chests. Above us, the sky was inky black and studded with a million stars. I have never in my life since seen so many stars and the dramatics of the night sky, shooting stars and unblinking planets and shiny little comets. Uncle usually told us stories, local folklore about ‘odiyans’, shapeshifters who could turn up anywhere and do infinite harm. They could only be identified if you spotted a part of their body missing, a thumb or an earlobe, something indiscernible. “Why, just two weeks ago, we saw one right here behind the house near the chicken coop.” Later, I’d toss and turn in bed, visions of murderous shapeshifters filling the dark room, until I gave up and crept downstairs to sleep in the adults’ room. Some ten minutes later, there would be the creak of the wooden floor and I’d know my brother too had abandoned his pride and self-esteem. A minute later, the bed would sag as he clambered on.

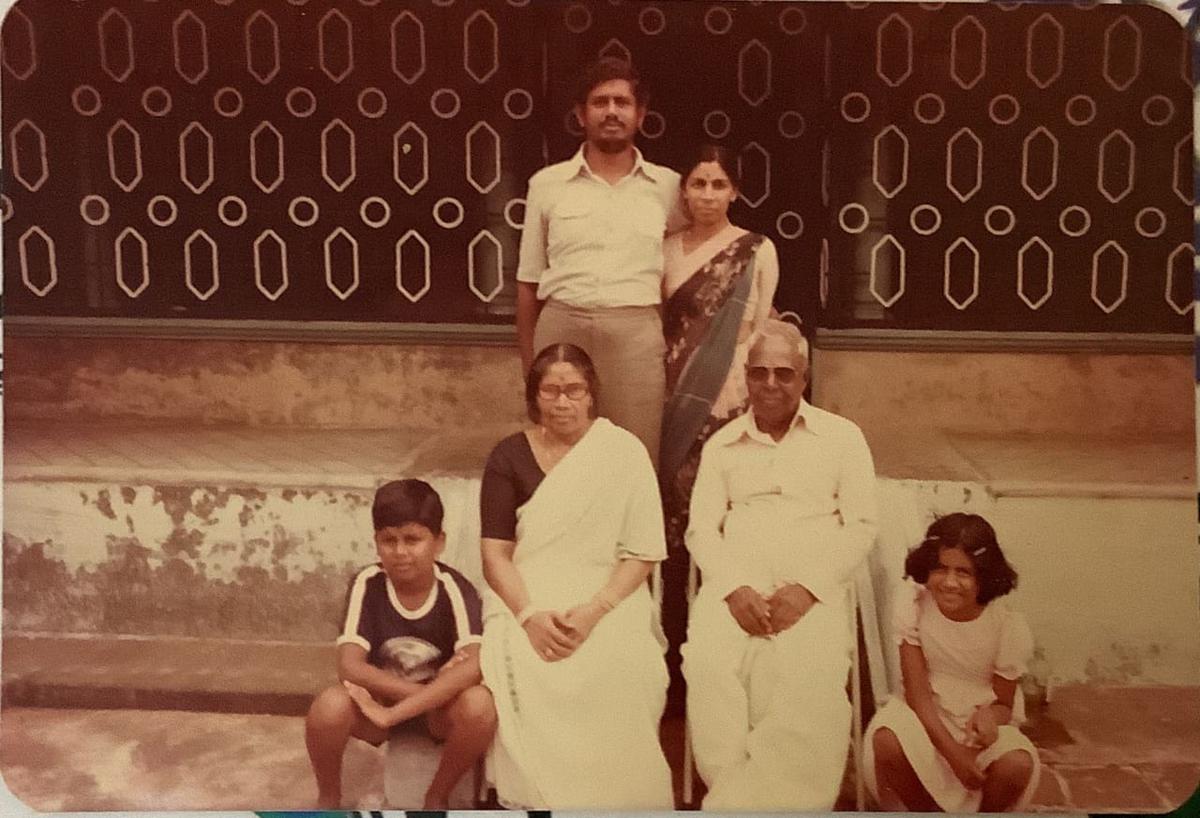

The author with her family

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

By the end of April, all our plans were over and we’d be home. The mango trees were weighed down by green fruits and we spent the mornings in the place where the branch made a V, biting into the crunchy tartness, trying to talk the other into going into the kitchen and getting more salt and chilli powder. I had a permanently sour molar, wincing while I ate and yet not being able to give up the wicked delight of a raw mango. We read and re-read books, the same old Nancy Drew or Hardy Boys. My brother sourced a new cassette from somewhere and we listened to the tracks all day – Boney M and Abba initially and later, Dire Straits and Pink Floyd. At 4 pm, my friend Jaicy would come calling, literally standing at the gate and yelling my name, and I’d join her to go play table tennis at the club. When we grew a little older, my brother and I stopped playing with each other and drifted off with our respective friends. “What should we do, what should we do?” that same old question but now with a new set of people. For hours we’d rue our lives, growing up in a place where there was nothing to do. But then, someone would think up an adventure or a mischief and off we’d go again.

Summer holidays in my childhood were an endless triumph of imagination over possession. We had nothing. But it is only in looking back, through eyes that have lived a life, that I realise that perhaps, we had everything.

The writer is the author of ‘Independence Day: A People’s History’.

[ad_2]

Source link