Since the start of this academic year, more than 3 lakh children in Delhi government schools, accounting for 18% of the total students enrolled in them, have been identified with “chronic absenteeism”, meaning that they have been absent from school for seven consecutive days or 20 out of 30 working days.

Of the 3,48,344 children identified with “chronic absenteeism” from April 1 to October 20, the biggest chunk is between the ages of 11 and 16, together making up 71.6% of these absentees. In the 11-13 age category, 1,35,558 children, or 19% of the students of this age, had this attendance track record and in the 14-16 age category, it was 1,13,876 children or 16% of the students of this age. Boys make up 55% of such “chronic absentees” while girls make up 45%.

Until September 30, as many as 7516 of the children enrolled in these schools did not attend school for a single day and attempts to contact their families were unsuccessful.

This data has been compiled by the Delhi Commission for Protection of Child Rights as part of its Early Warning System to curb absenteeism and drop-out rates in Delhi government schools.

After a two-year disruption because of the Covid-19 pandemic, compulsory attendance for students of all grades in Delhi schools was put back in place with the start of the 2022-2023 academic year on April 1.

This attendance tracking system began with the start of the academic year to identify children at risk and curb absenteeism.

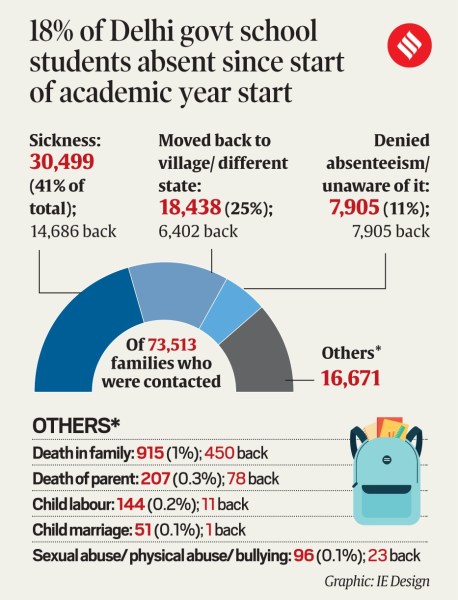

Of these 3.48 lakh children who have been chronically absent, the DCPCR has had telephonic conversations with the families of 73,513 children, which provides a picture of the reasons for their absence.

Within these 73,513 cases, the overwhelming majority, 41%, were reported by parents as being because of sickness. With the migrant character of the families of a large number of students, in 25% cases, parents said they had taken the child back for a visit to their village.

In 11% cases, the parent said they were not aware that their child had been absent from school – within this there is a section of cases where fathers answered the phone and were not aware of their child’s school attendance, and the other section is of parents who assumed that their child had gone to school but the child had not. These three reasons make up the bulk of the reasons reported by parents.

These are followed by death in a family (1%), death of a parent (0.3%), child labour (0.22%), child marriage (0.1%) and sexual abuse/physical abuse/bullying (0.1%).

Of these 73,513 children, 33,131 or almost half, returned to school after interventions—with an attendance of at least 33% monitored over a period of 30 working days being the metric of “back to school”.

The highest rate of success has been with those whose parents reported that they were not aware of their children’s absenteeism – 87% of such children whose parents were contacted were “back to school” after this intervention.

However, the lowest rates of success was for cases reported as being because of child labour and child marriage. Child labour was reported as the reason in 144 cases, of which 11 have been “back to school” while child marriage was reported in 51 of the cases, of which 1 returned.

For child labour cases, the poor rate of return can be primarily attributed to the low willingness of student or their family to let go of the additional household income. A significantly higher number of child labour cases, almost 90%, were reported amongst male students. A large portion of this can be due to the worsened economic situation because of Covid. For child marriage cases, the willingness of the girl child’s in-laws to send the girl child back to school has been low due to household responsibilities assigned to her.

“In many cases, the girl shifts back to their ancestral village where DCPCR has no jurisdiction,” said DCPCR chairperson Anurag Kundu.

The responsiveness to interventions has also varied across age categories. While 16% of children aged under 5 identified as chronic absentees were “back to school”, this tapered down to 9% each in 11-13, 14-16 and above 16 years categories.

Explaining the gap between the 3.48 lakh children identified as “chronic absentees” and the 73,513 with whom conversations have taken place, Kundu said, “Since our systems have been expanding, a majority of the interventions have only been in place in the last few months which is when these conversations have taken place. This is the major reason for the gap. Another small part is because the phone numbers provided by parents to the school are no longer in use.”

!function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s)

{if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function(){n.callMethod?

n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments)};

if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version=’2.0′;

n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0;

t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0];

s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)}(window, document,’script’,

‘https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js’);

fbq(‘init’, ‘444470064056909’);

fbq(‘track’, ‘PageView’);