[ad_1]

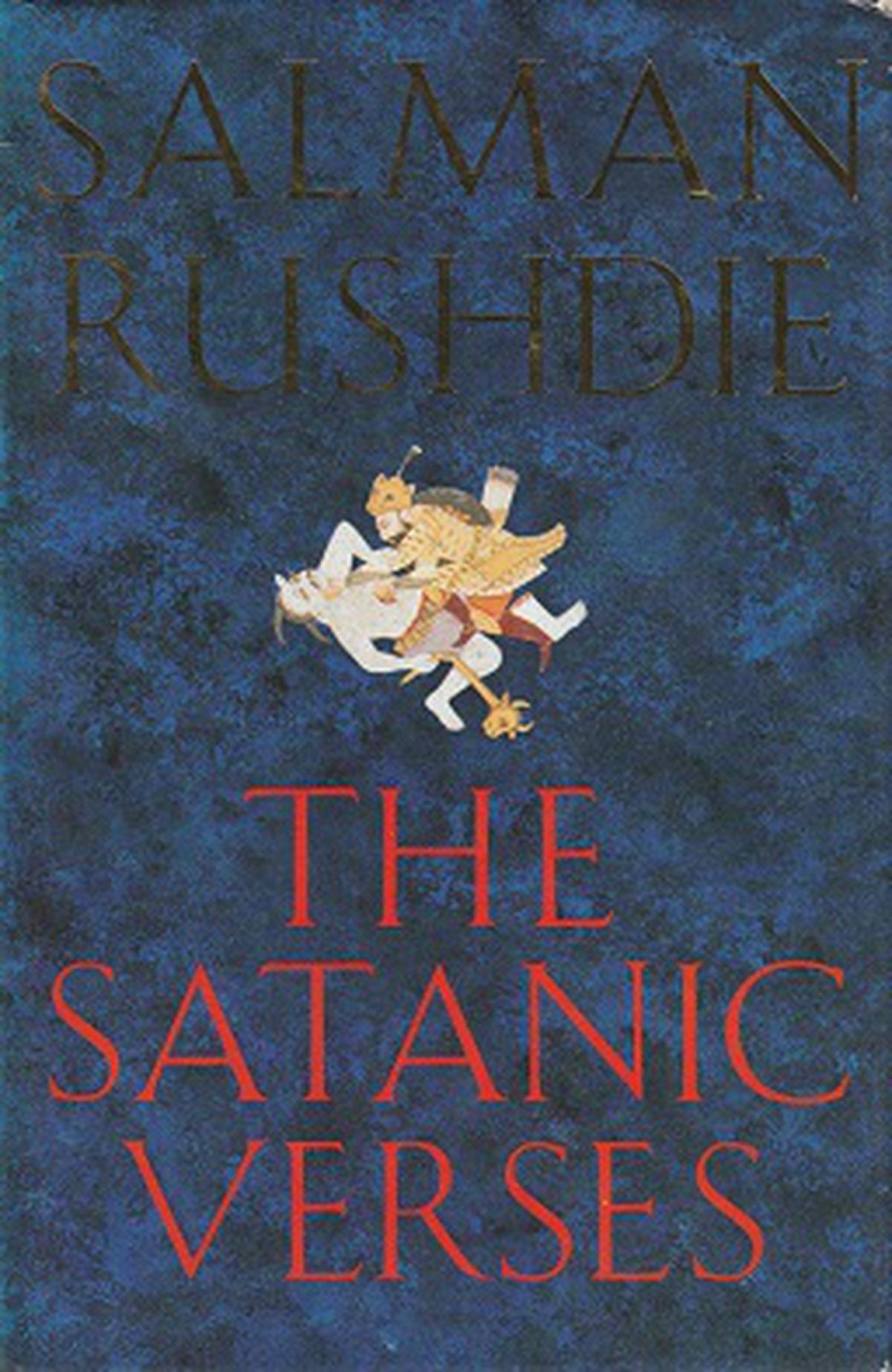

The attack on the author is a reminder that just as Midnight’s Children put literature from the subcontinent on the world literary map, The Satanic Verses put freedom of expression on the cultural map

The attack on the author is a reminder that just as Midnight’s Children put literature from the subcontinent on the world literary map, The Satanic Verses put freedom of expression on the cultural map

What you were is forever who you are. — Salman Rushdie, Midnight’s Children

When literary festival organisers in India baulked at inviting Salman Rushdie, I, like many advocates of freedom of expression, would react with righteous indignation. After the horrific stabbing at Chautauqua, I feel I understand their predicament a bit better. It was not just capitulation to political pressure. Which festival director would want to risk a Chautauqua? Despite all the security, there can still be enough of a gap for a determined 24-year-old with a knife.

That’s not to say that the lesson of Chautauqua is that freedom of expression must play second fiddle. It’s just that freedom of expression versus safety is an unenviable balancing act and one Rushdie himself was increasingly tired of.

In his 1991 address to Columbia University, he described himself as a bubble that floated above and through the world, deprived of reality, reducing him to an abstraction. “For many people I’ve ceased to be a human being. I’ve become an issue, a bother, ‘an affair’.”

Thirty years after that speech, Rushdie lying grievously injured in a pool of blood, reminded the world that he is both an issue and a human being. The two are not mutually exclusive.

The 75th anniversary of India’s independence should have been the time to revisit Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children. Instead, a young man who was not even born when the fatwa was issued has dragged us back into The Satanic Verses.

In the name of books

Some have cautioned against using the stabbing to tar Muslims generally, reminding us that fundamentalists come in all garbs. Others have stressed the need to stand up even more resolutely for freedom of expression. There’s been hand-wringing about how to change the hearts and minds of the brainwashed while a hardline Iranian paper said the hand of Rushdie’s attacker must be kissed.

Putting all these well-worn debates aside, it is a reminder that just as Midnight’s Children put literature from the subcontinent on the world literary map, The Satanic Verses put freedom of expression on the cultural map for many of us. It showed us what books could do and what could be done in the name of books (and that you didn’t have to read the book to do it). It ignited what writer Salil Tripathi memorably called “the offence Olympics”, where aggrieved groups realise that instead of not reading the book or not watching the film, they can weaponise their grievances, whether against The Satanic Verses or Deepa Mehta’s Fire or Perumal Murugan’s Madhorubhagan or Aamir Khan’s Laal Singh Chaddha.

The Satanic Verses is still cited as the moment (along with the Shah Bano case) when the ruling Congress Party stood exposed of pandering for votes. It also showed how those of us who are not particularly religious underestimate the power religious symbols have in the lives of the faithful. One of Rushdie’s opponents said, “Free speech is a non-starter”, to which he retorted, “No, sir, it is not. Free speech is the whole thing, the whole ball game. Free speech is life itself.”

These are fighting words but all around the world, it’s increasingly clear that freedom of expression is not something electorates care about deeply even if Rushdie’s books have shot up the Amazon charts. Rushdie at least got state protection. In India, the murders of Gauri Lankesh, Narendra Dabholkar and Govind Pansare did not cause political upheaval. Rukmini S. writes in her book Whole Numbers and Half Truths, published last year, that according to a 2015 Pew Research Global Poll, Indians gave less importance to freedom of expression than any other country, except Indonesia.

A candlelight vigil for murdered journalist Gauri Lankesh, in New Delhi, September 2017.

| Photo Credit: Getty Images

Lonely and thankless battle

Another survey of four Indian States showed that as levels of education rose, so did support for restrictions on freedom of expression. No wonder the Indian political establishment did not feel the need to vociferously speak up when Rushdie was stabbed. It shows that for the political class, he’s still “an issue, a bother, ‘an affair’.”

However, just because it’s not a vote getter does not mean freedom of expression is unimportant. It only means that those who fight for it, on behalf of all of us, fight a lonely and thankless battle.

But let’s never forget, Rushdie did not want to be the apostle for freedom of expression. He just wanted to tell stories.

Years ago, I had interviewed him when he was on a publicity tour for Shalimar the Clown (2005). After all the usual questions, which he answered with practised aplomb, I asked, “Do you have any good fatwa jokes?” He stopped short, grinned, and said, “They are all really bad jokes. The best-known one is, ‘what’s blonde, has big breasts and lives in Tasmania?’ The answer is Salman Rushdie, which unfortunately is not the case.” And then he laughed.

It was a bad joke but I hope someday Rushdie can make that joke again.

The writer is the author of ‘Don’t Let Him Know’ (2015).

[ad_2]

Source link