[ad_1]

Sixty-six songs have been given the Bob Dylan treatment in The Philosophy of Modern Song. Maybe the book (his “first book of new writing since 2004’s Chronicles: Volume One and since winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2016” as the blurb breathlessly proclaims) should have been called The Philosophy of Modern American Song, or English song, but that is a mere little quibble.

As the book does not claim to be a history of popular music, the songs are not organised chronologically. The flitting nature of the arrangement echoes Dylan’s stream-of-consciousness style. You almost feel like you will soon stumble on a blind commissioner or Einstein disguised as Robin Hood or at least Cinderella sweeping up after Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot as you zip through the 356-page dissection of American pop culture.

Rants and laughs

Sixty years on, the conscience of several generations, and companion through countless long dark tea times of the soul, Dylan continues to bewitch and bedazzle with his liquid, live-wire prose. “Words dissolved into runs of vowels without the traffic lanes of consonants,” is just one example. There are laughs as well to be had with Dylan wondering when Twitchy Woman morphed into the very successful Witchy Woman, what would happen if one more letter were removed from the title to record a song about an itchy woman!

Bob Dylan performing at the Oakland Coliseum Arena, Oakland, California, in 1978.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Each song is a springboard into the winding lanes of a keen mind, with magpie-like references to pop culture markers. Elvis Presley’s ‘Money Honey’ talks about art and money. “Art is a disagreement. Money is an agreement. The only reason money is worth anything is because we agree it is.” So, while we can argue all night about if it is Dylan’s signature, an autopen, or Dylan using the autopen as he uncharacteristically explained on Facebook, on the 900 limited editions of the book, we cannot argue about the $600 (gasp) cost.

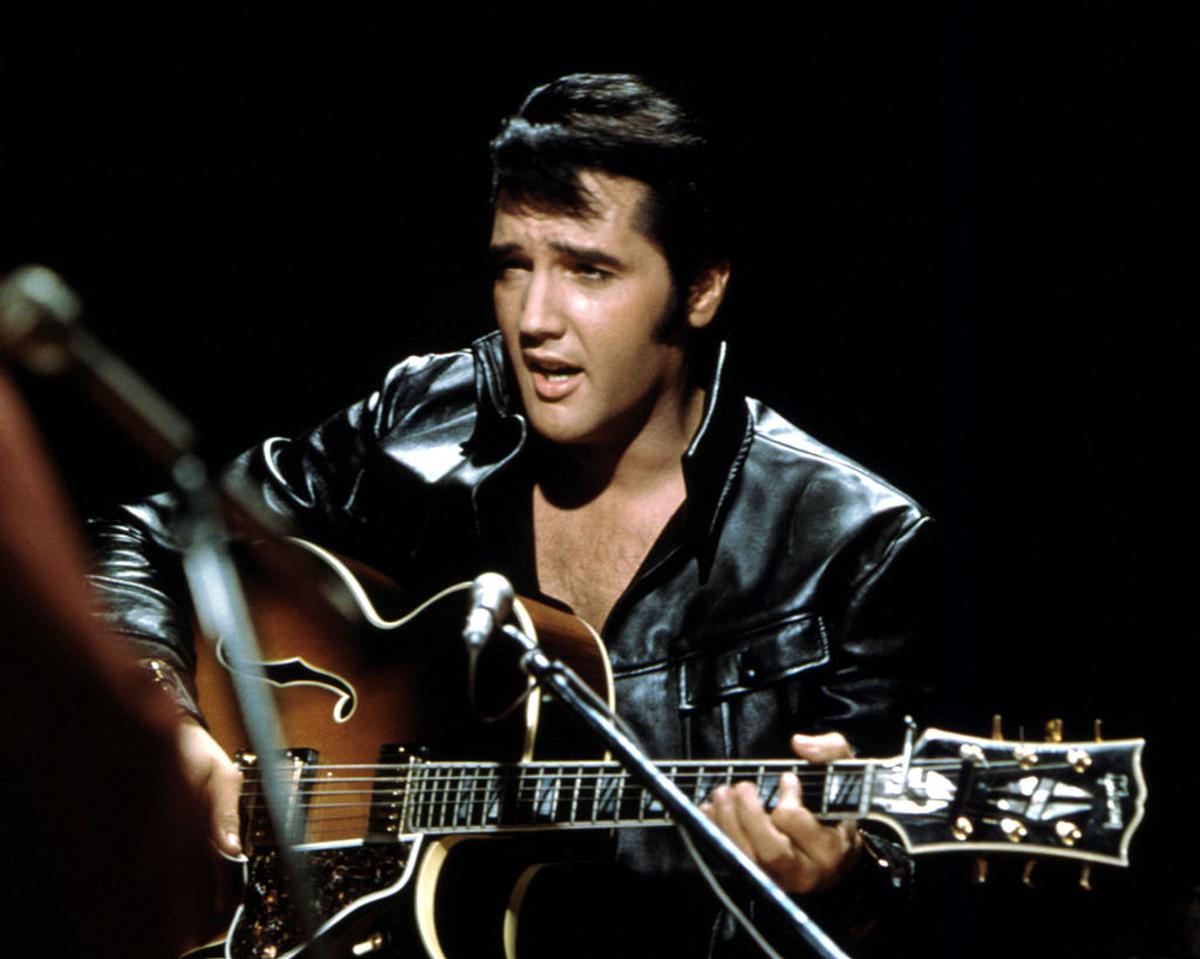

Rock and roll musician Elvis Presley during a performance in 1968.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

The Who’s ‘My Generation’ features a discussion on the arrogance of ignorance while Harry McClintock’s ‘Jesse James’ talks about the dangers of being an outlaw.

Johnnie Harrison Taylor performed a wide variety of genres, from blues, rhythm and blues, soul, and gospel to pop, doo-wop, and disco.

Johnnie Taylor’s ‘Cheaper to Keep Her’ talks about marriage, divorce that is a “10 billion-dollar-a-year industry” and rather contrarily of the benefits of polygamy — et tu Bob? The Fugs’ ‘CIA Man’ has Dylan wondering why DC Comics or Marvel did not think of a CIA Man in their meta-human stables. “Stan Lee would have had a ball drawing up this guy.”

‘On the Street where you Live’ which a love-struck Jeremy Brett (the same who made for such an amazing Sherlock Holmes in the 80s TV show) sang to Eliza in My Fair Lady, has Dylan musing that sometimes that is as close as you can be to someone.

‘Hard Rain’s…’ vibes

‘Your Cheatin’ Heart’ by Hank Williams with his drifting cowboys provokes a rant against niche marketing. “There isn’t an item on the menu that doesn’t have half a dozen adjectives in front of it… Enjoy your free range cumin infused cayenne-dusted heirloom reduction.” Carl Perkins ‘Blue Suede Shoes’ talks of the fact that there are more songs written about shoes than any either item of clothing and slyly that shoes do not give up their secrets easily — “like the Mafia code of omertà, there was nothing revealed on the tongue.”

Hank Williams in a publicity photo in 1951.

| Photo Credit:

Wiki Commons

Mose Allison’s ‘Everybody Cryin’ Mercy’ finds Dylan drawing a line between “mercy” and “mercantile” (they share the same Latin root). Edwin Starr’s ‘War’ (“Disruptive explosions like some sort of geopolitical herpes”) has Dylan writing “One mark of civilisation is the ability to increase the distance between yourself and the person you kill,” bringing to mind his ‘A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall’ and the executioner’s face that is always well hidden.

Dylan’s pen portraits of musicians are acute. There is Elvis who is “all sullen eyes and sharp cheekbones,” and The Platters “exuding hipness the way James Dean exhaled cigarette smoke.”

Bob Dylan performing at Hyde Park, London, in 2019.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

On the craft of song writing Dylan writes, “A big part of song-writing is editing,” and “Putting melodies to diaries doesn’t guarantee a heartfelt song.” Dylan succinctly writes against the formulaic approach with “in music and in ditch digging — what started out as a groove quickly becomes a rut.” The magic that makes the perfect marriage of lyrics and melody, Dylan writes is not chemistry, but its wilder precursor, alchemy. “You gain nothing from understanding,” is his answer to the obsessives who want to know what exactly he meant by the walking antique or the hypnotist collector.

Labyrinth of a mind

Each essay is divided into two with the first part being almost like supplementary lyrics to the song and the second leading you through the labyrinth of his mind full of connections to the esoteric and ordinary. The book is profusely peppered with lovely photographs directly or tangentially related to the songs.

The audiobook is a splendid companion piece to the book. Dylan narrates in his echoey, gravelly voice with Jeff Bridges, Oscar Isaac, Rita Moreno, Jeffrey Wright, Sissy Spacek, John Goodman, Alfre Woodard, Steve Buscemi, Helen Mirren, and Renée Zellweger for company.

At the end of the book, you feel like you spent time with a friend who is an excellent raconteur and allowed you a glimpse into the workings of his mind and craft. Whether it is a true snapshot or more obfuscation is part of the appeal of the book.

And after all the other questions have been answered there remains one, why has Dylan thanked the crew of Dunkin’ Donuts in his acknowledgements?

The Philosophy of Modern Song; Bob Dylan, Simon & Schuster, ₹2,499.

mini.chhibber@thehindu.co.in

[ad_2]

Source link