[ad_1]

Veteran architect Ramu Katakam’s new memoir goes behind his unusual childhood, his design influences, and his sensitive, sustainable designs

Veteran architect Ramu Katakam’s new memoir goes behind his unusual childhood, his design influences, and his sensitive, sustainable designs

Ramu Katakam’s autobiography, Spaces in Time: A Life in Architecture, is as free-wheeling as his life. An architect, author and constant traveller, he has always sought universal meaning with a humility that accepted mentorship whenever he found it.

Ramu Katakam’s autobiography is as free-wheeling as his life

His peripatetic existence commenced early, being the son of a parent in the highest echelons of the Indian government in the immediate decades after independence. His childhood memories are suffused with the strange and sublime spaces he grew up in — a railway saloon, a tent, a Madras family home, a courtyard house in the Hutongs of Beijing, and a houseboat moored on an island in the Nile, among others. His growing up years are criss-crossed with many figures significant to the 20th century, some in passing and some enough to leave lasting impressions.

Katakam’s architectural practice mirrors this multivalence as well, both in the variety of sites he has designed in as well as the diversity of projects he has worked on, including such memorable projects as the meditation centre at Nagarjunakonda, Andhra Pradesh — built with mud excavated from the site and where the design ‘was evolved in the form of a small village with separate rooms, like houses, along pathways that followed the contours of the land’. His house, Axis Mundi, was shortlisted for the Aga Khan awards in 2007. While he has now deferred practice to pursue research on the traditional architecture of Tamil Nadu, in his memoirs, he treats both the built and the unrealised with equal affection. Edited excerpts from an interview:

Inside Katakam’s Bengaluru home, Axis Mundi

| Photo Credit: Special arrangement

In your memoir, you describe a childhood living in a variety of spaces and places. How do you look back on your many homes in terms of architectural inspiration?

My homes in all parts of India and abroad have certainly inspired my architectural evolution. Although I was young when I was in China, my fascination for all things Chinese has remained with me. I have used the concept of a walled area before entering a house in the Sainik Farms house where the parking separates the house from the entrance court. The stint in Egypt, too, must have played in my mind as I have been studying the pyramid form and have used it in my latest design. This house is being built in a rocky landscape of Tamil Nadu.

Ramu Katakam with his parents at the tents pitched where the present Supreme Court stands in Delhi

| Photo Credit: Special arrangement

The railway saloon, circa 1945

| Photo Credit: Special arrangement

Your autobiography has amazing glimpses of encounters with several influential figures, people as diverse as Rajiv Gandhi, Kim Philby and Pink Floyd. The period between the 50s and the late 70s set the influences (and tone) for your own architectural practice from 1977. In retrospect, what are your learnings from those times?

I am not sure how meeting these people influenced my architecture, but I always felt it was necessary to be part of a global world and try to be a world citizen. It did occur to me that creativity began with small beginnings. Pink Floyd started out as architects that found their calling in music and went on to become figures that influenced a generation. It is a question of destiny and skill that helps shape our lives, but one need not be world famous to live a creative life.

Among the most influential architects I have worked with is Sir Leslie Martin who was my teacher in college and later architect to the Secretariat in Taif, Saudi Arabia, where I was the site architect. On his site visits, he had lots of time to discuss his design philosophy and what he believed in. An important architect of his time, he treated younger architects as equals — something I have tried to do since. My friend and design teacher, Barry Gasson, who designed the seminal Burrell Museum in Glasgow inside a park, allowed me to design outside the box of the international style.

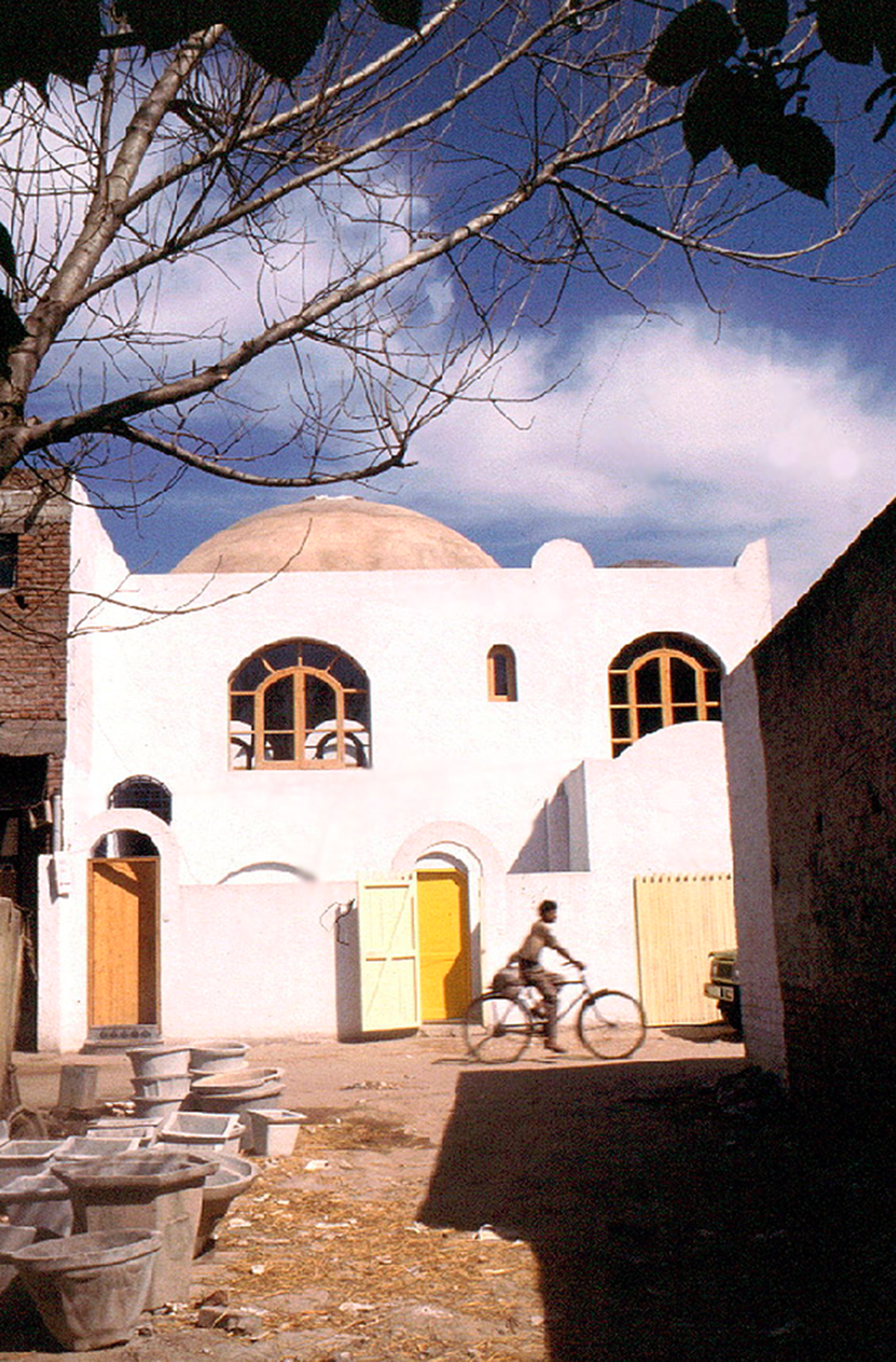

The front elevation of Khirkee gallery (1994) in Delhi. India’s first exclusive gallery for sculptors, it is built in brick and mud like the village buildings surrounding it

| Photo Credit: Special arrangement

You have talked extensively about places visited and people met, but is it at all possible to describe your essential muses when it comes to your design?

Perhaps Luis Barragán’s approach to modern design in architecture has been a big influence in the way I think and work. He has pursued silence and space to build his extraordinary buildings. Like him, serenity, beauty, intimacy and reaching out to an individual’s soul through the experience of architectural space underline my aspirations. Hassan Fathy too, with his breaking away from the international style and building very simple buildings was instrumental in my trying to build ‘simpler’. The muses have been many, from the vernacular of Greek island buildings, to the stepwells of India. Architecture, I believe, is the intervention of man with nature and they were careful in the past to not damage their surroundings.

ALSO READ | The best chance for architecture

It is unusual to hear of an architect who ‘puts aside’ his practice. What moved you to do so? How do your current interests and pursuits fulfil you, as compared to your architectural practice?

I have not given up design — just the idea of a practice and the problems of running one. The rigour of running a practice was too much for me and after 30 years, it was more satisfying finding excellent buildings than trying to build them. However, design is always satisfying and the few buildings I designed were an attempt to fulfil a desire of finding what we want in our lives.

Not having to spend time in going to an office every day and being distracted by pressing problems, one had the time to travel and seek out places that resulted in writing books that allowed me to clarify ideas of the past and the present. It also allowed me to design a few projects that demanded attention to detail and design. I was also fortunate to have a couple of clients that allowed this freedom of design resulting in homes and buildings they felt provided them a refuge from the outside world.

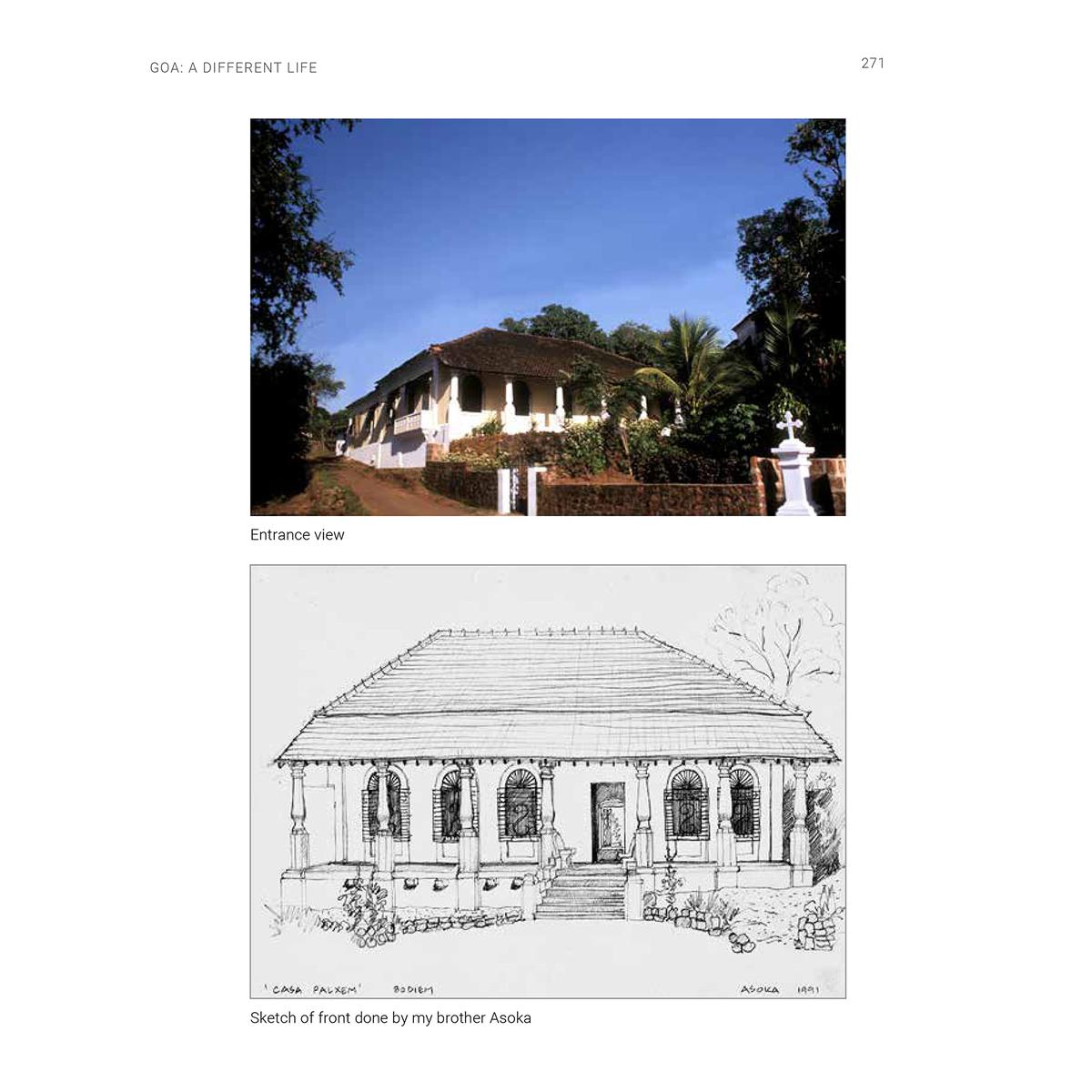

Casa Palxem, the Portuguese style villa in Goa that Ramu Katakam took a year to restore and renovate

Sketches of Casa Palxem (1994) from Spaces in Time: A Life in Architecture

| Photo Credit: Special arrangement

Through your books, ‘Glimpses of Architecture in Kerala’ and ‘Cosmic Dance in Stone’, you have consistently connected the contemporary with the universal. What is it about these universal spaces — timber architecture in Kerala, or the stones of Petra, Angkor Wat, Ellora — that appeals to you?

With the appeal of modern architecture dwindling, I found myself being drawn to buildings that had a timeless quality and lasted for centuries yet were as fresh as when they were made. They also were able to bring about an emotion of joy as we visited these wonderful structures. Modern architecture does not seem to bring this sense of wonder, although that may be too general. Is it not strange that the Ellora caves are just an hour away from Mumbai and a tiny percentage actually go there, while the large majority miss out on what I consider one of the most important buildings of India.

A residence in Delhi (1984) that attempts to adapt the elements of a colonial bungalow using simple construction methods

| Photo Credit: Special arrangement

Your life and practice in Delhi does parallel the times of independent India, and you have been witness to its progress as a democracy, and its expressions through built form. How do you perceive the flurry of building activity in Delhi today and its attempt to transfigure its historical core?

This is a tricky question to answer and needs a longer answer. If the flurry you refer to is Gurugram, then we are faced with a nightmare of urban living that has no future. If it is the refiguring of the Central Vista, it is really not much better than the manner in which the British Imperial might was imposed on India with the imposing edifices of the Raj. They happen to be well designed, but the intent was to show the might of a ruler.

READ | How to build for the future: India’s shortlists at the upcoming World Architecture Festival 2022

Gandhi understood this and the power of architecture. He suggested the government start a new office after independence but this went unheeded. The present Prime Minister may have built a palatial house, but remember Nehru too moved into Teen Murti House. Unfortunately, the present efforts in Delhi have to compete with Shahjahanabad and Imperial Delhi and fall well short in architectural terms.

The writer is Professor of Architecture at Sir JJ College of Architecture, Mumbai.

[ad_2]

Source link