[ad_1]

Dr Rajani Thiranagama was a feminist, academic, scientist, and a fighter for truth and justice

| Photo Credit: The Hindu archives

“All the most powerful forces are invisible” observes Maali, the narrator of Shehan Karunatilaka’s Booker Prize-winning The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida. “Love, electricity, wind. And the waves following a bomb blast.” Unspoken is the other powerful and invisible force animating his book: grief.

The book is set in 1989, a bloody year in Sri Lanka. Maali Almeida dies, wakes up in purgatory and finds himself amongst the ghosts of the newly dead and those who refuse to move on. Chief among them is a woman in a white sari who helps guide him on his journey. Maali recognises her, from her face and her ‘toothpaste smile’, as a Tamil human rights activist assassinated by the Tamil Tigers.

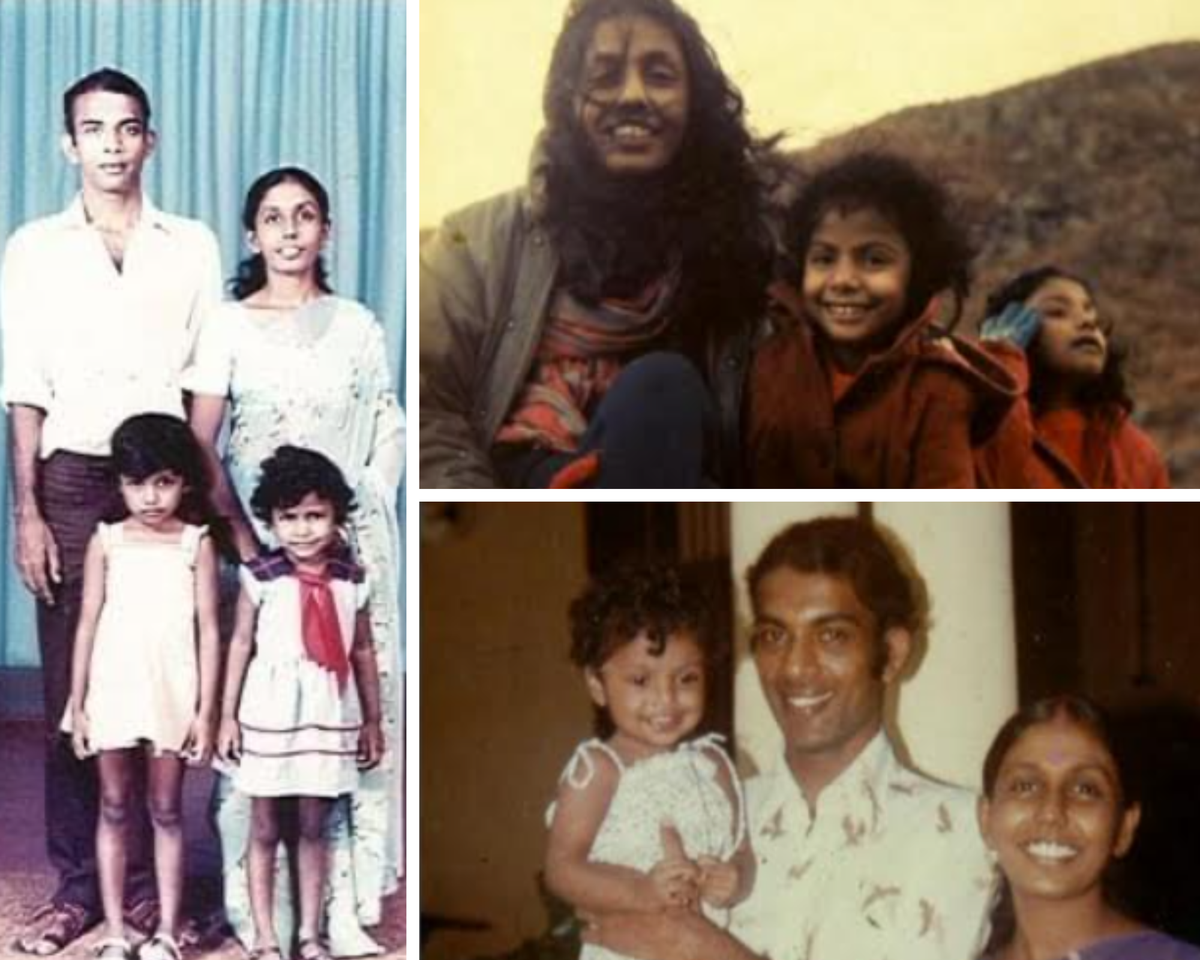

Rajani Thiranagama’s daughter, Narmada

Glimpses from the family album

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

At this point, I too had a moment of recognition: this was Dr Rajani Thiranagama — feminist, academic, scientist, a fighter for truth and justice. She is also my darling Amma, who I lost when she was 35 and I was 11.

She appears constantly throughout the novel, scolding Maali, setting him straight, trying to organise the chaos of death for all new ghosts. She says, “None of us want to be here — I had to leave my two little daughters behind.” She tells him that she finds ways of visiting the dreams of her husband and her daughters, and whispering to them.

Karunatilaka’s invocation of the underworld and its spirits powerfully conjures the experience of living through civil war. The metaphor of the purgatorial waiting room describes so well the horror of that time. To be alive but also already dead, an ordeal we leavened with dark humour: “Have you heard?” the joke went, “they’re knocking on people’s doors at midnight. And when you call out, ‘Who is it?’, they reply, ‘Who do you want it to be?’” The punchline was that the wrong answer could kill you. We joked that the Indian Army came to kill our Tigers, but they ended up killing our chickens. It is these recollections, a reality for which I had no words, that Karunatilaka’s book captures so well; the visceral experience of living with the madness, of the bodies and secrets created every day, and the never-ending killing.

In The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida is a woman with a ‘toothpaste smile’ that Maali recognises as a Tamil human rights activist assassinated by the Tamil Tigers.

Courageous in pursuing truth

As a child living in a Jaffna occupied first by the Sri Lankan army, then by the Indian army, and then during the all-out bombing, shelling and cross-fire that followed the breakdown of the peace accord, I was surrounded by death. Confined to our house by curfews, we spent our nights in darkness, petrified that any movement or light could provoke a soldier to shoot at the shadows. It felt as if our houses and bomb shelters had become a grave, ready for us to perish in.

But when I looked to my mother Rajani, I found the powerful centre of my world. As other people fled, or fell into silence, she grew taller, her spine straighter. She loved her people and did not want to leave them. When civilian life fell apart, she made an announcement on the radio that the medical faculty of the University of Jaffna would continue its classes and exams. She woke at 4am to prepare for her classes. In the evening, she documented human rights abuses.

ALSO READ | Chronicles of a carnage foretold

Rajani didn’t just teach her students; she fought for them when they were arrested or went missing. With other feminists, she helped found a home for women who had faced sexual violence in war — Poorani, ‘the whole woman’. My mother and other academics at the University put together a book, The Broken Palmyrah, determined not to allow the atrocities we had witnessed and the lives we had lost to go undocumented. She was fearless in pursuing truth and recorded atrocities by the Sri Lankan army, Indian army, the LTTE and other Tamil militant groups.

A women’s refuge set up by peace activist Rajani Thiranagama, who campaigned to end Sri Lanka’s civil war

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

The unheard voice

Karunatilaka never met my mother, and yet his fictional version of her is so fully realised that it catches an elemental part of her, almost as if her fierce and impatient spirit had somehow managed to return to me. In reality, my mother left one day and never returned. I heard the shots being fired in the distance, unaware my life was changing forever. My mother was on her way home when she was shot. She scolded her assassin and told him not to kill her. Her words did not save her.

I stayed up late to finish Seven Moons, and as I fell asleep I felt her hand press my back — so lightly, so fleetingly. In that moment I glimpsed the world full of her love that had been torn from me in an instant, and I gasped at the enormity of that loss. The absent touch, the unheard voice — invisible and powerful forces.

The writer lives in London and does policy work on labour market justice and workers’ rights for a trade union.

[ad_2]

Source link