Anna Sujatha Mathai’s first poems were published as part of P. Lal’s ‘Anthology of Modern Indian Poetry’ in 1969.

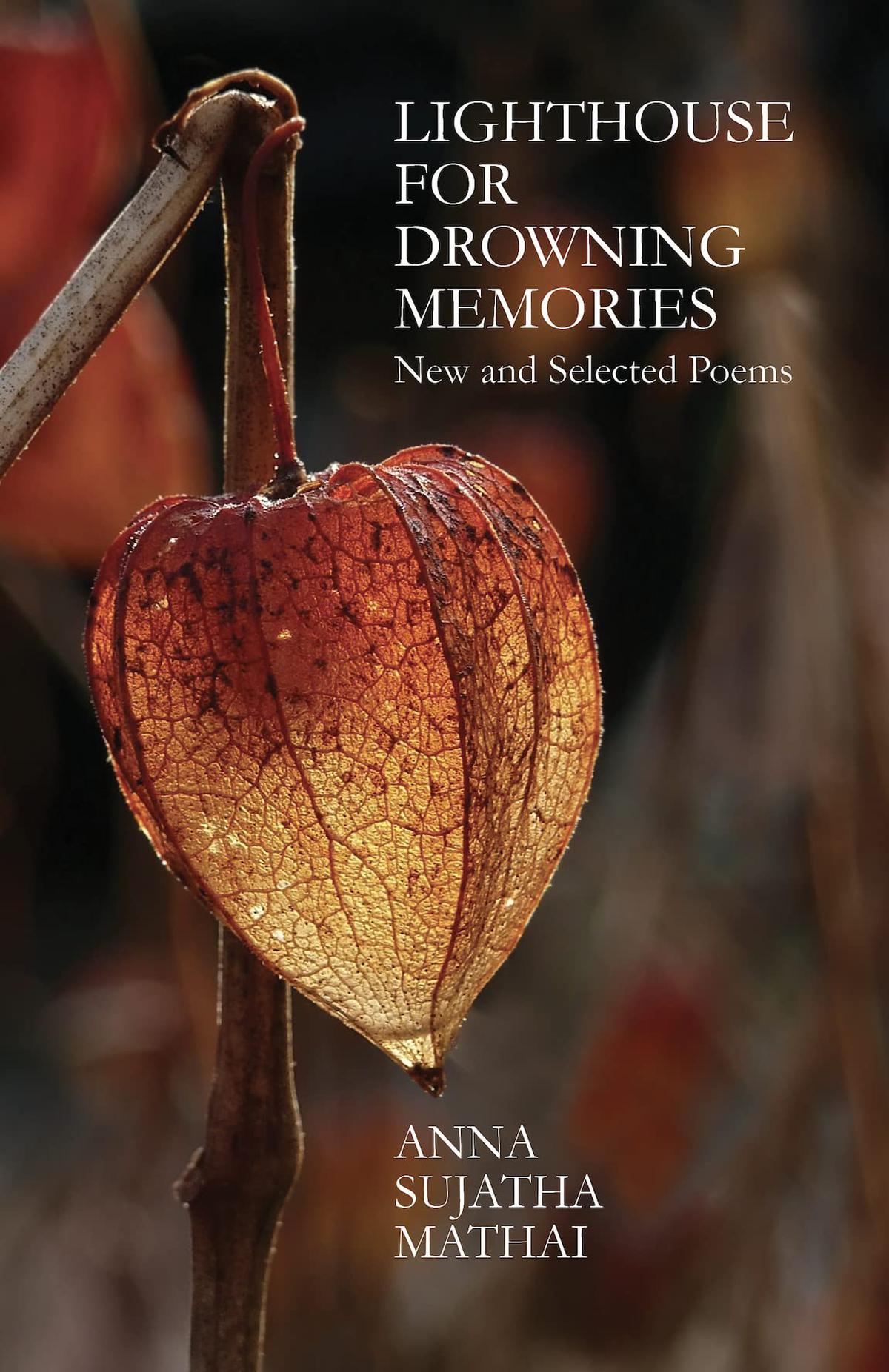

We, drowning, clutching, lost, straying — a line from Anna Sujatha Mathai’s recent poem ‘Hints in a World Caught Between Living and Dying’, and her newest book, Lighthouse for Drowning Memories (Poetrywala, 2022), serve as an ironic premonition, a weather-vane pointer, to her recent death.

Nearly a week after her passing on March 16, hardly any publication, mainstream or otherwise, in English or Malayalam, had carried the news of her demise — a stark reminder of the relative anonymity of the Indian poet, in life and death.

Mathai, 89, was part of the first wave of poets, along with Ranjit Hoskote, Tabish Khair, myself and others, to be published in the ‘New Poetry’ series, selected by Nissim Ezekiel and published by Rupa in 1991.

At the same time, Penguin, under the poetry editorship of Dom Moraes, published the first volumes by C.P. Surendran, Jeet Thayil, and others. It was a watershed moment for English-language poetry from India and all of us rode that euphoric wave together.

Born in Kerala to Syrian Christian parents, Mathai’s early years were spent in Delhi as her father was head of the English department at St. Stephen’s College. She completed her B.A. (Honours) in English Literature from New Delhi’s Miranda College, and got her postgraduate degree in Social Studies from Edinburgh University.

Anna Sujatha Mathai in 2015.

| Photo Credit:

Wiki Commons

Drama was her great passion, and she won several prizes during her college days. Her marriage at the age 20, and move to Edinburgh, ended her theatre dreams. After working in London, York and Sheffield, she (and her husband) moved back to Bengaluru.

Mathai’s first poems were published as part of P. Lal’s Anthology of Modern Indian Poetry in 1969. Since then, she has published six collections, namely Crucifixions (1970), We the Unreconciled (1972), The Attic of Night (1991), Life on My Side of the Streets (2005), Mothers Veena and Selected Poems (2013), and Lighthouse for Drowning Memories (2022).

She was polite and soft-spoken, elegantly dressed in a pure cotton or silk sari. Her poetry was familial, down-to-earth, simple and unambitious. She preferred the lyric mode, and responded to feminist issues, and personal/ political situations, with sensitivity and compassion.

Clutching at words

Words are fish/ swimming in the ocean/ Unless there are waves/ the fish won’t come up/ unless there is excitement/ the words won’t swim up/ that’s how a poem starts/ with waves of excitement. These lines from the eponymous poem, ‘Words’, sum up Mathai’s “excitement” and point to the wellspring of her poetry.

Over the years, she and I met many times in each other’s homes, at poetry readings and literary conferences. Lately, a rather serious chronic illness had slowed her down, and our meetings became scarce.

“It would be best for me to admit that I have no fixed writing practice. But I do keep notebooks and pens handy near my bed, and do try [though I often fail] to seize the passing thought or what seems like a wonderful line. It is, of course, a very special day if I am able to pin down the line or lines; if the thought becomes clear in some lines that flow. If I write a whole poem, where the words seem to fall into place, it is a matter of joy for me all day, or all night, if I missed my sleep it doesn’t matter!” wrote Mathai in The Punch Magazine. “My recent illness has made things more difficult, especially as I can’t wander around the house searching for a line in a book, or for some old paper or book, or just sitting and reading aloud some lines of poetry! But I have still managed to snatch some poems from the dark, which makes me happy and proud!”

With her demise, we have lost yet another accomplished poet in recent years. The world of Indian poetry is poorer for her passing.

The writer’s book, ‘Anthropocene’, co-won the Rabindranath Tagore Literary Prize for 2021-22. Currently, he is fellow and writer-in-residence at NIROX, South Africa.

.jpg)