[ad_1]

Bukhara – A Journey on the Silk Route, at the National Crafts Museum

| Photo Credit: Special arrangement

The Silk Route. Approximately 6,437 km from China to Europe. 1,500 years of trade. Caravanserais carrying silk and spices, precious stones and porcelain, jade and glassware, even horses, the plague, and gunpowder. And in the centre of this world: Tashkent, Samarkand, Bukhara, Khiva and Fergan valley. Here came Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, Islam, and Communism. Here swept in nomadic and pastoral Turkic and Mongol tribes. Gengis Khan laid siege here, and out of this land came the brutal but brilliant Timur, the scholar Al Biruni, and the scientist Ibn Cena.

A woman’s ikat chapan from the 19th century. The jacket got its silky polish by being hammered with a wooden mallet and probably egg white

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

It is no wonder that the world has now woken up to the riches of present-day Uzbekistan. Two ongoing exhibitions in Paris — at the Louvre and the Institut du Monde Arabe — focus on its treasures. And inspired by them is a third. In India. Bukhara – A Journey on the Silk Route, at the National Crafts Museum in Delhi. However, unlike the other two, the body of the exhibit is taken from the personal archives of David Housego and Mandeep Nagi, the couple at the helm of Shades of India and focuses on the area’s nomadic legacy. Shades of India is a brand known for its expertise with Indian craft and textile manipulation.

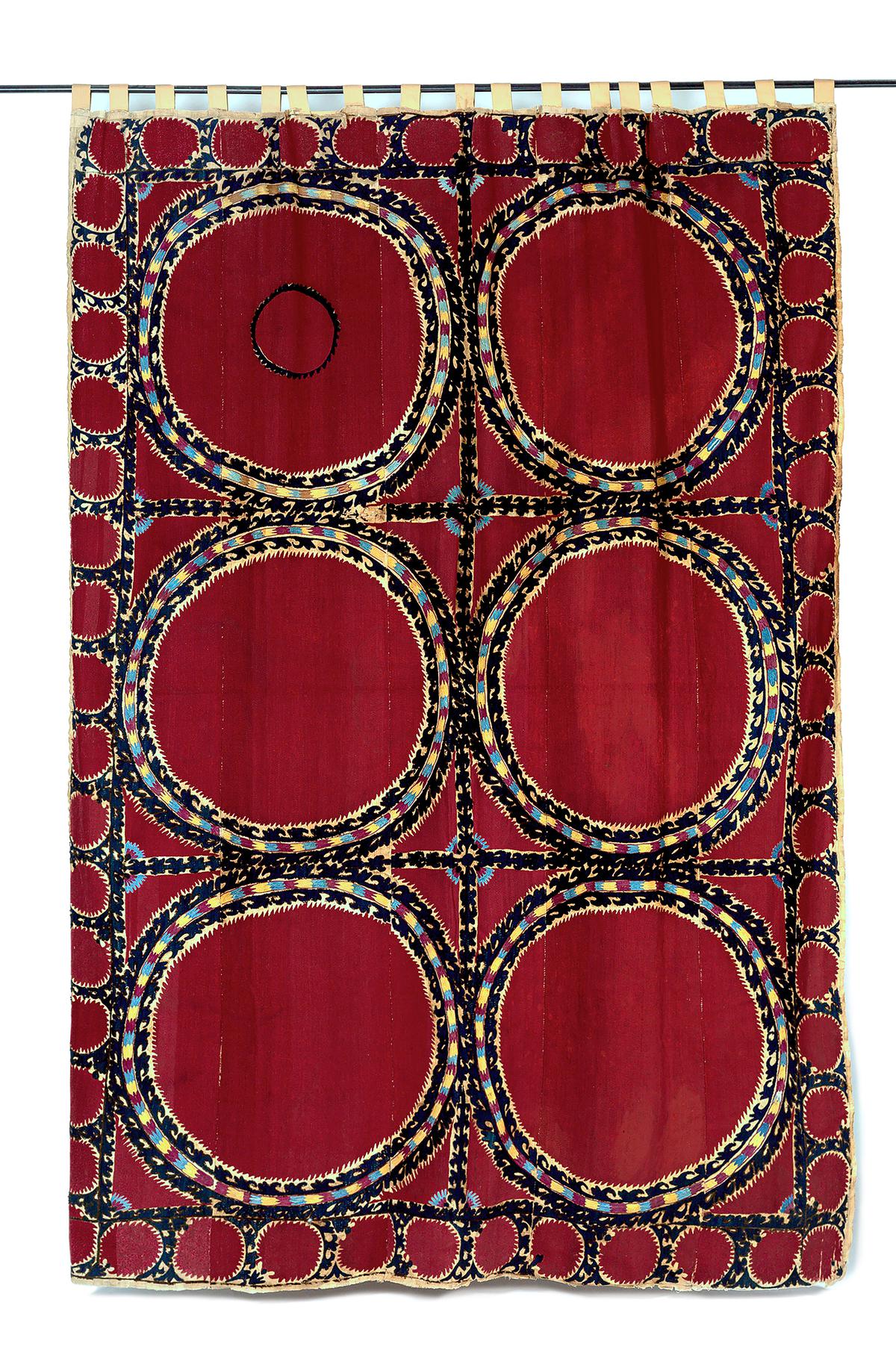

A Tashkent suzani (silk on cotton) from the early 19th century

| Photo Credit:

Special arrangement

For the love of suzanis

The story begins in Afghanistan. In the early 1970s, David Housego, then a journalist with the Financial Times, was sent there on assignment. While wandering around the bazaars, his attention was drawn to a beautiful red hand-embroidered textile panel or suzani. It had large red circles and black rings on top. “I fell in love with it,” he says. “What first struck me was how contemporary they were. They had a sense of colour that I could relate to as abstract paintings.”

That s uzani (Persian for needle), he later discovered, was a 19th century piece from Tashkent. It is part of the 40 pieces —16 suzanis, 14 rugs, six chapans or coats, and some jewellery and accessories — that comprise Bukhara. Housego had already been collecting tribal rugs during his time in Iran, prior to his purchase of the suzani from Afghanistan. But that piece started a lifelong interest in Central Asian work.

Rugs

Beshir rugs, as they were called in Bukhara, were thought to be made in the nearby small town of Beshir, but are most likely to have been woven by the tribal Turkmen Ersari weavers living along the banks of the Amu Darya. They are known for their inventive design and colour.

The double ikat of the chapan is a technique that has now disappeared.

A quick primer: suzanis originated from the nomadic tribes of Central Asia, where they were used in yurts or tents as everything from protective coverings to prayer mats and bedsheets. They were created in thin strips and sewn together. What deserves particular attention is the abstraction of the floral motifs and the fineness of the needlework. “Motifs like circles represented the sun and the moon, and were locally [at that time] interpreted as being both,” says Housego. The circles also reflected pomegranates, shorthand for fertility. “ Suzanis were made as dowries for a wedding. [Work on them] would often begin when a daughter was born,” he adds.

Suzanis on view at the Bukhara exhibition

| Photo Credit:

Gulshan Sachdeva

Tracking the motifs

All the exhibits were made over a short 100-year period when Uzbekistan was relatively stable and the cities were prosperous before the Russian collectivisation and industrialisation of the early 20th century. Everything is vegetable and hand dyed. “In Bukhara, the city was divided into different communities and some specialised in dyeing. So, the Jewish community specialised in indigo and the Tajik specialised in the reds and yellows that are very striking features of both the ikats and of the suzanis,” says Housego.

The display was planned by Mandeep Nagi and Amita Goal. Divided into three parts, it was designed to weave together the common threads that run through the ikats, suzanis, rugs, and even the jewellery. The pieces are layered with influences of the different empires that ruled Uzbekistan, from Kushan to Achaemenid to Islamic. There is also the influence of the Silk Route itself.

“You can see that some of the pieces were influenced by Chinese motifs. The embroidery silks also came from China,” says Nagi. At the same time, the boteh or paisley design comes from India. The use of small strips and later joining them together is similar to Phulkari as is the intent of creating textiles to bless daughters. Floral motifs of tulips, carnations and roses and irises transport you to Persian and Mughal gardens. “These are things you won’t see a generation later,” she says. “Will anybody know about this craft and culture? It’s already rare now.”

Bukhara: A Journey on the Silk Route is on till February 15 at the National Crafts Museum.

The writer is a fashion consultant and commentator based in New Delhi.

[ad_2]

Source link