In the coming years, NASA will be busy at the moon. A giant rocket will loft a capsule with no astronauts aboard around the moon and back, perhaps before the end of summer. A parade of robotic landers will drop off experiments on the moon to collect reams of scientific data, especially about water ice locked up in the polar regions. A few years from now, astronauts could return there, more than a half-century since the last Apollo moon landing.

Those are all part of NASA’s 21st-century moon program named for Artemis, who in Greek mythology was the twin sister of Apollo.

Early Monday, a spacecraft named CAPSTONE is scheduled to launch as the first piece of Artemis to head to the moon. Compared to what is to follow, it is modest in size and scope.

There will not be any astronauts aboard CAPSTONE. The spacecraft is too tiny, about as big as a microwave oven.

This robotic probe won’t land on the moon. But it is in many ways unlike any previous mission to the moon. It could serve as a template for public-private partnerships that NASA could undertake in the future to get a better bang for its buck on interplanetary voyages.

“NASA has gone to the moon before, but I’m not sure it’s ever been put together like this,” said Bradley Cheetham, CEO and president of Advanced Space, the company that is managing the mission for NASA.

Coverage of the launch will be begin at 5 a.m. Eastern time Monday on NASA Television. The rocket has to launch at an exact moment, at 5:50 a.m., for the spacecraft to be lofted to the correct trajectory.

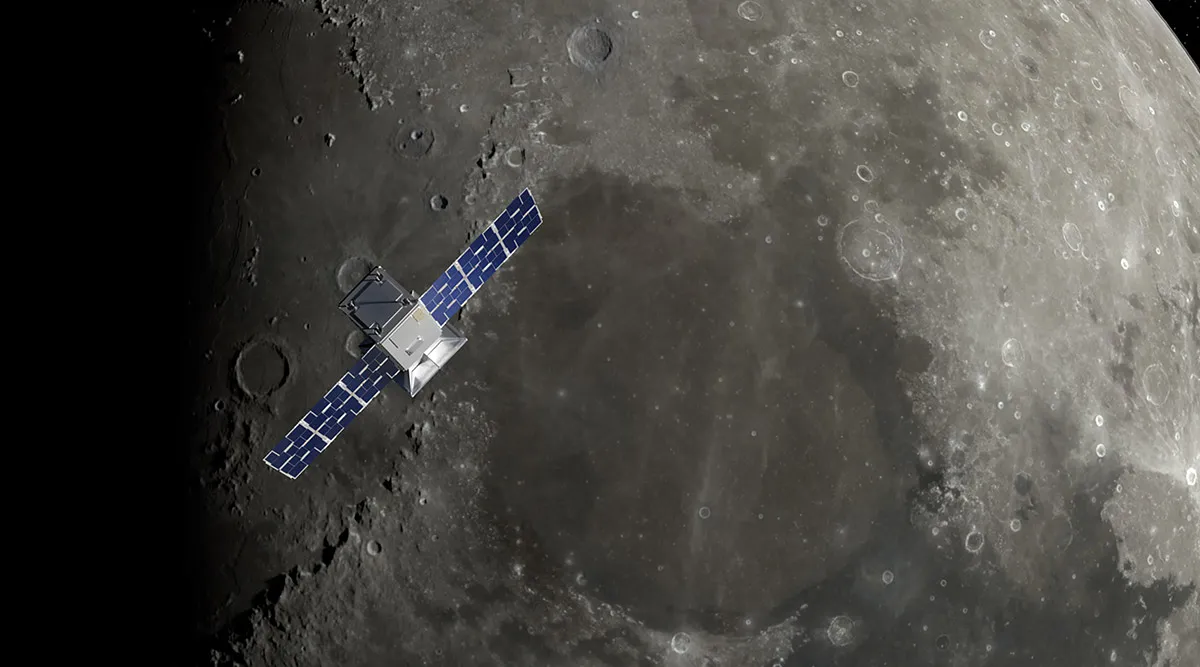

The full name of the mission is the Cislunar Autonomous Positioning System Technology Operations and Navigation Experiment. It will act as a scout for the lunar orbit where a crewed space station will eventually be built as part of Artemis. That outpost, named Gateway, will serve as a way station where future crews will stop before continuing on to the lunar surface.

CAPSTONE is unusual for NASA in several ways. For one, it is sitting on a launchpad not in Florida but in New Zealand. Second, NASA did not design or build CAPSTONE, nor will it operate it. The agency does not even own it. CAPSTONE belongs to Advanced Space, a 45-employee company on the outskirts of Denver.

An undated photo by Dominic Hart/NASA of Dylan Schmidt, the CAPSTONE spacecraft’s assembly integration and test lead, installing its solar panels at Tyvak Nano-Satellite Systems. Early on Monday, June 27, 2022, the spacecraft is scheduled to launch as the first piece of Artemis, NASA’s 21st-century moon program, to head to the moon. (Dominic Hart/NASA via The New York Times)

An undated photo by Dominic Hart/NASA of Dylan Schmidt, the CAPSTONE spacecraft’s assembly integration and test lead, installing its solar panels at Tyvak Nano-Satellite Systems. Early on Monday, June 27, 2022, the spacecraft is scheduled to launch as the first piece of Artemis, NASA’s 21st-century moon program, to head to the moon. (Dominic Hart/NASA via The New York Times)

The spacecraft is taking a slow but efficient trajectory to the moon, arriving Nov. 13. If weather or a technical problem causes the rocket to miss that instantaneous launch moment, there are additional chances through July 27. If the spacecraft gets off the ground by then, it will still get to lunar orbit on the same day: Nov. 13.

The CAPSTONE mission continues efforts by NASA to collaborate in new ways with private companies in hopes of gaining additional capabilities at lower cost more quickly.

“It’s another way for NASA to find out what it needs to find out and get the cost down,” said Bill Nelson, NASA’s administrator.

Advance Space’s contract with NASA for CAPSTONE, signed in 2019, cost $20 million. The ride to space for CAPSTONE is small and cheap too: just under $10 million for a launch by Rocket Lab, a U.S.-New Zealand company that is a leader in delivering small payloads to orbit.

“It’s going to be under $30 million in under three years,” said Christopher Baker, program executive for small spacecraft technology at NASA. “Relatively rapid and relatively low cost.”

Even Beresheet, a shoestring effort by an Israeli nonprofit to land on the moon in 2019, cost $100 million.

“I do see this as a pathfinder for how we can help facilitate commercial missions beyond Earth,” Baker said.

The primary mission of CAPSTONE is to last six months, with the possibility of an additional year, Cheetham said.

The data it gathers will aid planners of the lunar outpost known as Gateway.

When President Donald Trump declared in 2017 that a top priority for his administration’s space policy was to send astronauts back to the moon, the buzzwords at NASA were “reusable” and “sustainable.”

That led NASA to make a space station around the moon a key piece of how astronauts would get to the lunar surface. Such a staging site would make it easier for them to reach different parts of the moon.

The first Artemis landing mission, which is scheduled for 2025 but likely to be pushed back, will not use Gateway. But subsequent missions will.

NASA decided that the best place to put this outpost would be in what is known as a near-rectilinear halo orbit.

Halo orbits are those influenced by the gravity of two bodies — in this case, the Earth and the moon. The influence of the two bodies helps make the orbit highly stable, minimizing the amount of propellant needed to keep a spacecraft circling the moon.

The gravitational interactions also keep the orbit at about a 90-degree angle to the line-of-sight view from Earth. (This is the near-rectilinear part of the name.) Thus, a spacecraft in this orbit never passes behind the moon where communications would be cut off.

The orbit that Gateway will travel comes within about 2,200 miles of the moon’s North Pole and loops out as far as 44,000 miles away as it goes over the South Pole. One trip around the moon will take about a week.

In terms of the underlying mathematics, exotic trajectories like a near-rectilinear halo orbit are well understood. But this is also an orbit where no spacecraft has gone before.

Thus, CAPSTONE.

“We think we have it very, very well characterised,” said Dan Hartman, program manager for Gateway. “But with this particular CAPSTONE payload, we can help validate our models.”

In practice, without any global positioning system satellites around the moon to pinpoint precise locations, it might take some trial and error to figure out how best to keep the spacecraft in the desired orbit.

“The biggest uncertainty is actually knowing where you are,” Cheetham said. “You never in space actually know where you are. So you always have an estimate of where it is with some uncertainty around it.”

Like other NASA missions, CAPSTONE will triangulate an estimate of its position using signals from NASA’s Deep Space Network of radio dish antennas and then, if necessary, nudge itself back toward the desired orbit just after passing the farthest point from the moon.

CAPSTONE will also test an alternative method of finding its position. It is unlikely that anyone will spend the time and expense to build a GPS network around the moon. But there are other spacecraft circling the moon, and more will likely arrive in the coming years. By communicating with each other, a fleet of spacecraft in disparate orbits could in essence set up an ad hoc GPS.

Advanced Space has been developing this technology for more than seven years, and now it will test the concept with CAPSTONE sending signals back and forth with the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter.

As it started developing CAPSTONE, Advanced Space also decided to add a computer-chip-scale atomic clock to the spacecraft and compare that time with what is broadcast from Earth. That data can also help pinpoint the spacecraft’s location.

Because Advanced Space owns CAPSTONE, it had the flexibility to make that change without getting permission from NASA. And while the agency still collaborates closely on such projects, this flexibility can be a boon both for private companies like Advanced Space and for NASA.

“Because we had a commercial contract with our vendors, when we needed to change something, it didn’t have to go through a big review of government contracting officials,” Cheetham said.

The flip side is that because Advanced Space had negotiated a fixed fee for the mission, the company could not go to NASA to ask for additional money. More traditional NASA contracts known as “cost-plus” reimburse companies for what they spend and then add a fee — received as profit — on top of that, which provides little incentive for them to keep costs under control.

This is similar to NASA’s successful strategy of using fixed-price contracts with Elon Musk’s SpaceX, which now ferries cargo and astronauts to and from the International Space Station at a much lower cost than the agency’s own space shuttles once did. For SpaceX, NASA’s investments enabled it to attract non-NASA customers interested in launching payloads and private astronauts to orbit.

Until CAPSTONE, Advanced Space’s work was mostly theoretical, not building and operating spacecraft.

The company is still not really in the spacecraft-building business. “We bought the spacecraft,” Cheetham said. “I tell people the only hardware we build here at Advanced is Legos. We have a great Lego collection.”

In the past couple of decades, tiny satellites known as CubeSats have proliferated, enabling more companies to quickly build spacecraft based on a standardized design in which each cube is 10 centimeters, or 4 inches, in size. CAPSTONE is among the largest, with a volume of 12 cubes, but Advanced Space was able to buy it, almost off-the-shelf, from Tyvak Nano-Satellite Systems of Irvine, California.

That still required a lot of problem-solving. For example, most CubeSats are in low-Earth orbit, just a few hundred miles above the surface. The moon is nearly a quarter-million miles away.

“No one’s flown a CubeSat at the moon,” Cheetham said. “So it makes sense that no one’s built radios to fly CubeSats at the moon. And so we had to really dive in to understand a lot of those details and actually partner with a couple of different folks to have the systems that could work.”

Hartman, the Gateway program manager, is excited about CAPSTONE but says it is not essential to moving ahead with the lunar outpost. NASA has already awarded contracts for the construction of Gateway’s first two modules. The European Space Agency is also contributing two modules.

“Can we fly without it?” Hartman said of CAPSTONE. “Yes. Is it mandatory? No.”

But he added, “Any time you can reduce error bars in your models is always a good thing.”

Cheetham is thinking about what could come next, perhaps more missions to the moon, either for NASA or other commercial partners. He’s also thinking farther out.

“I’m very intrigued about thinking about how could we go do a similar type thing to Mars,” he said. “I’m actually pretty interested personally in Venus, too. I think it doesn’t get enough attention.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

!function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s)

{if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function(){n.callMethod?

n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments)};

if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version=’2.0′;

n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0;

t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0];

s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)}(window, document,’script’,

‘https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js’);

fbq(‘init’, ‘444470064056909’);

fbq(‘track’, ‘PageView’);