[ad_1]

Imagine you visit a tourist attraction and you get someone to click a picture of you, only for some random person to come into the frame to “photobomb” you. They essentially ruin the image by taking away attention from the main subject; you. Interestingly, astronomers looking for habitable planets also get “photobombed” and NASA scientists are considering many solutions to solve this.

According to a new NASA study, when a telescope is pointed at an exoplanet, the light reflected by the planet could be “contaminated” by light from other planets in the same system. The research has been published in Astrophysical Journal Letters and models how this “photobombing” effect would impact a space telescope’s ability to observe habitable exoplanets. It also suggests potential methods to overcome the issue.

“If you looked at Earth sitting next to Mars or Venus from a distant vantage point, then depending on when you observed them, you might think they’re both the same object. For example, depending on the observation, an exo-Earth could be hiding in [light from] what we mistakenly believe is a large exo-Venus,” said Prabal Saxena, a NASA scientist who led the research, in a press statement. Venus has surface temperatures hot enough to melt lead and is therefore considered hostile to life. This kind of mixing could lead to scientists missing out on potentially habitable planets.

This phenomenon stems from the “point-spread function” (PSF) of the target exoplanet. PSF is the image created due to the diffraction of light coming from the source and becomes larger than the source for very distant objects, like an exoplanet. The PSF’s size depends on the aperture of the telescope and the wavelength at which the image was captured. For distant exoplanets, the PSF may resolve in such a way that multiple planets or planets and satellites could seem to morph into one.

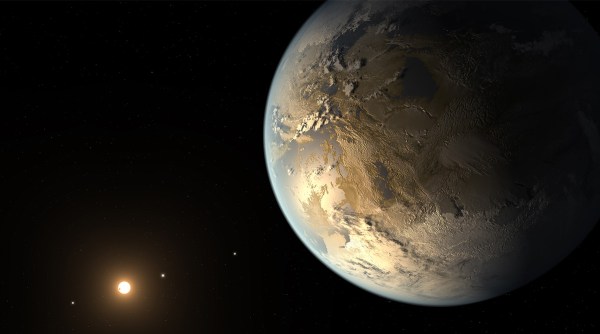

Artist’s concept of Kepler-186f, an Earth-size exoplanet orbiting a red dwarf star in the constellation Cygnus. (Image credit: NASA / Tim Pyle)

Artist’s concept of Kepler-186f, an Earth-size exoplanet orbiting a red dwarf star in the constellation Cygnus. (Image credit: NASA / Tim Pyle)

When that happens, the data gathered about the exoplanet would be affected by whatever objects were photobombing it. This would complicate or even prevent the detection and confirmation of an exo-Earth, a potentially Earth-like planet outside of our solar system.

Scientists examined a similar scenario, except reversed. They modelled a situation where an astronomer from another 30 light years away could be looking at the Earth with a telescope similar to the one recommended by the 2020 Astrophysics Decadal Survey. “We found that such a telescope would sometimes see potential exo-Earths beyond 30 light-years distance blended with additional planets in their systems, including those that are outside of the habitable zone, for a range of different wavelengths of interest,” said Saxena.

The study proposes multiple strategies to deal with this issue. One of the methods involves developing new methods of data processing to remove the possibility of such a photobombing phenomenon skewing the results of a study. Another method proposed is to study systems over time; this could help avoid a possibility where planets with close orbits would appear in each other’s PSF. The study also discusses the use of multiple telescopes and increasing the size of telescopes to reduce the effect.

!function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s)

{if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function(){n.callMethod?

n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments)};

if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version=’2.0′;

n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0;

t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0];

s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)}(window, document,’script’,

‘https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js’);

fbq(‘init’, ‘444470064056909’);

fbq(‘track’, ‘PageView’);

[ad_2]

Source link