[ad_1]

Speaking to Muzaffar Ali is replete with old world charm. His impeccable Urdu diction, the pauses, the grace… all combine to take you back to a time that has long been consigned to pages of history. There is an element of wistfulness, some nice nostalgia when he talks of Kotwara, his ancestral house, where history resided on the mantelpiece and riches lay in the courtyard. His father, Raja Syed Sajid Hussain, was a man with much to commend. A taluqdar wedded to humanism, yet a man who liked certain privileges that life bestowed on him. “The abolition of zamindari was a game changer. Some taluqdars could not come to terms with it. As I saw changing social matrix, it was a signal for me that I could not be in this feudal zone. I had to do something on my own,” says noted filmmaker-fashion designer and sufi music lover Muzaffar Ali.

His autobiography, interestingly titled Zikr: In the Light and Shade of Time is being talked about as much for the frankness with which he describes his early days as the warmth he displays when talking of his family, films and poetry. As he says, “Poetry would come and receive me with open arms. After the unfulfilled saga of Zooni, I found new meaning in poetry and music.”

He was drawn to the hospices of Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti in Ajmer, and Delhi, the city of saints, something that would enrich his Sufi oeuvre in the years to come. In 2001, it manifested itself as a celebration of sufi music with Jahan-e-Khusrau in Delhi. He teamed up with the formidable Begum Abida Parveen from Pakistan, and soon music lovers were swaying to Raqs-e-Bismil. It was uplifting as long as it lasted. Will it be possible to revive the heady days? “Really difficult in the current climate. The walls between the two nations have been raised too high, but yes, in future, if an opportunity presents itself, then why not? Sufi music brought people together. Religion was not supposed to pit people against each other but celebrate each other.”

It all stemmed from his abiding love for sufiism, Chishti, Nizamuddin Auliya, Amir Khusrau and Rumi. “Their words gave me wings,” he says. These were the wings which saw him redefine his relationship with Kotwara, embrace the place he once regarded with studied indifference.

A model at the ‘Weaver of dreams -The Passion of Muzaffar Ali of Kotwara’ fashion show in Hyderabad in 2018.

| Photo Credit:

RAMAKRISHNA G

On his own terms

“Once I left Kotwara, I never really went back for a considerable stretch of time. I had no interest in feudal paraphernalia. Things changed after my father died,” says Muzaffar. Between leaving Kotwara and coming back, he went into the world of advertising, then had a brief stint at Air India before entering the world of Hindi cinema. In 1990, he launched his couture brand House of Kotwara with wife Meera to revive the traditional crafts and textiles of the Awadh region. All on his own terms, and in his own inimitable way.

Back in the late 1970s when the common man was relishing the escapist fare churned out by dream merchants, he chose to do Gaman, a film steeped in realism. In what was to become his signature, Muzaffar listened to his heart and chose to work with music composer Jaidev and singer Chhaya Ganguly for the film. The result was a winner called ‘Aap ki yaad aati rahi’ and a timeless melody ‘Seene main jalan aankhon mein toofan’. Incidentally, the songs were penned by the reclusive Shahryaar. “I chose Shahryaar obviously because of our Aligarh Muslim University connection and also because his poetry resonated with me. It possibly drove me to do certain kind of films. But yes, he was not meant for Bombay cinema. He never shifted to Bombay,” recalls Muzaffar.

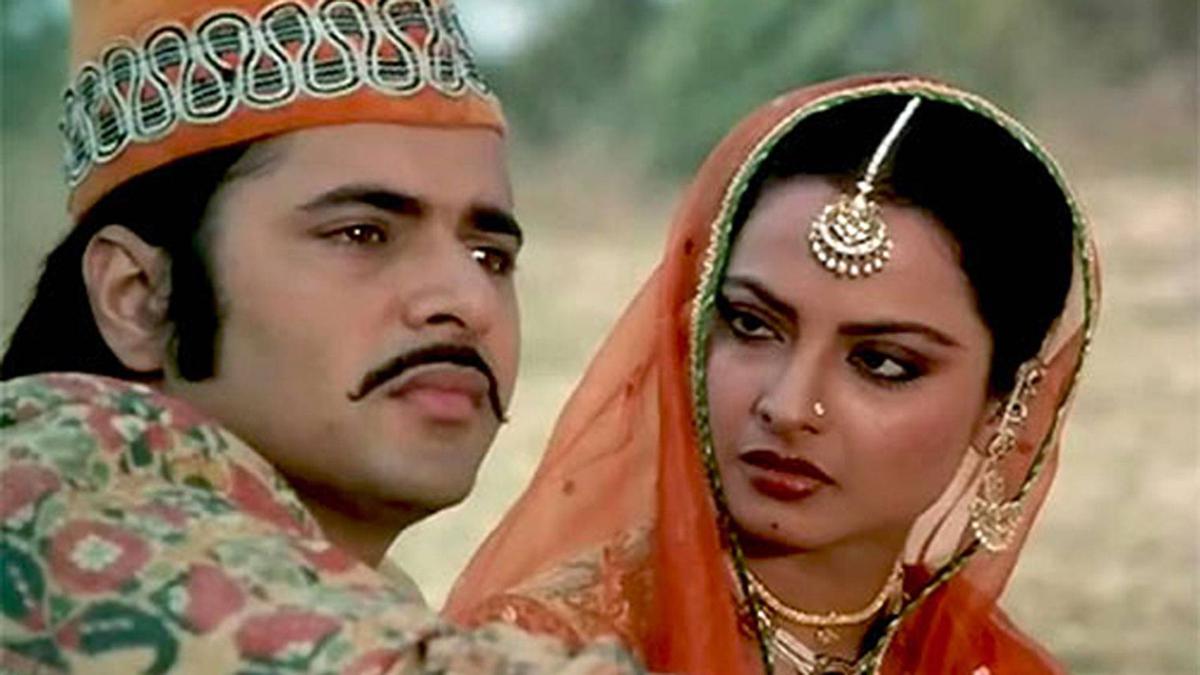

Rekha and Farooq Sheikh in ‘Umrao Jaan’

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

This deep respect for Shahryaar’s poetry gave birth to the timeless songs of Umrao Jaan such as ‘In ankhon ki masti ke’, ‘Justuju jis ki thhi’ and ‘Ye kya jagah hai doston’. Jaidev who was initially drafted, was replaced. “Because of my proximity, I could take a few liberties with Shahryaar but with Jaidev sahab, things did not work out for Umrao Jaan. His compositions were good but they lacked certain energy. Also, I was not entirely happy with the way Madhurani sang them. So I went to Khayyam sahab. And Asha Bhosle came in. She wanted to read the novel on which the film was based to do justice to the songs. She came disarmed and fully committed,” says Muzaffar about the film which changed Asha Bhosle’s image of just being an excellent cabaret song artiste. “Her Urdu diction took many by surprise. Each song for her was like an act of worship. She would write ‘Om’ on top of the page, then write down the lyrics, repeating them quietly before going for recording. Her dedication was matched by Rekha on whom most songs were picturised. Each song opened a window to Rekha’s soul. Everybody associated with Umrao Jaan seemed to be listening to his or her inner calling, much like the way a sufi would.”

Begum Abida Parveen performing at the Jahan-e-Khusrau 2005 edition

| Photo Credit:

Gurinder Osan

Umrao Jaan became part of history. It was for Muzaffar what Mughal-e-Azam was for K. Asif or Pakeezah for Kamal Amrohi. “You could look at it that way,” he says.

Of course, he also made Aagaman soon after Umrao Jaan and Anjuman a little later. In the former, Anupam Kher made his debut, in the latter, Shabana Azmi actually sang four songs! However, any talk of his film journey would be incomplete without the mention of Zooni, a film based on the peasant poetess of Kashmir, Habba Khatoon. Zooni was being shot in Kashmir in 1989 when militancy raised its ugly head. Even as Dimple Kapadia left the director spellbound with her performance, the hero Vinod Khanna, did not show up for many shooting schedules. With militancy rising, it was a race against time to complete the film and Muzaffar was not helped by the hero’s absence. Will the film ever be completed? He sighs, saying, “We lived on hope for a long time, but things never really changed. Today things are totally different.”

[ad_2]

Source link