Architect and Mumbaikar Robert Stephens’ new book, Bombay Imagined, records unrealised plans for the city — from an underground railway to monsoon-regulating canals

Architect and Mumbaikar Robert Stephens’ new book, Bombay Imagined, records unrealised plans for the city — from an underground railway to monsoon-regulating canals

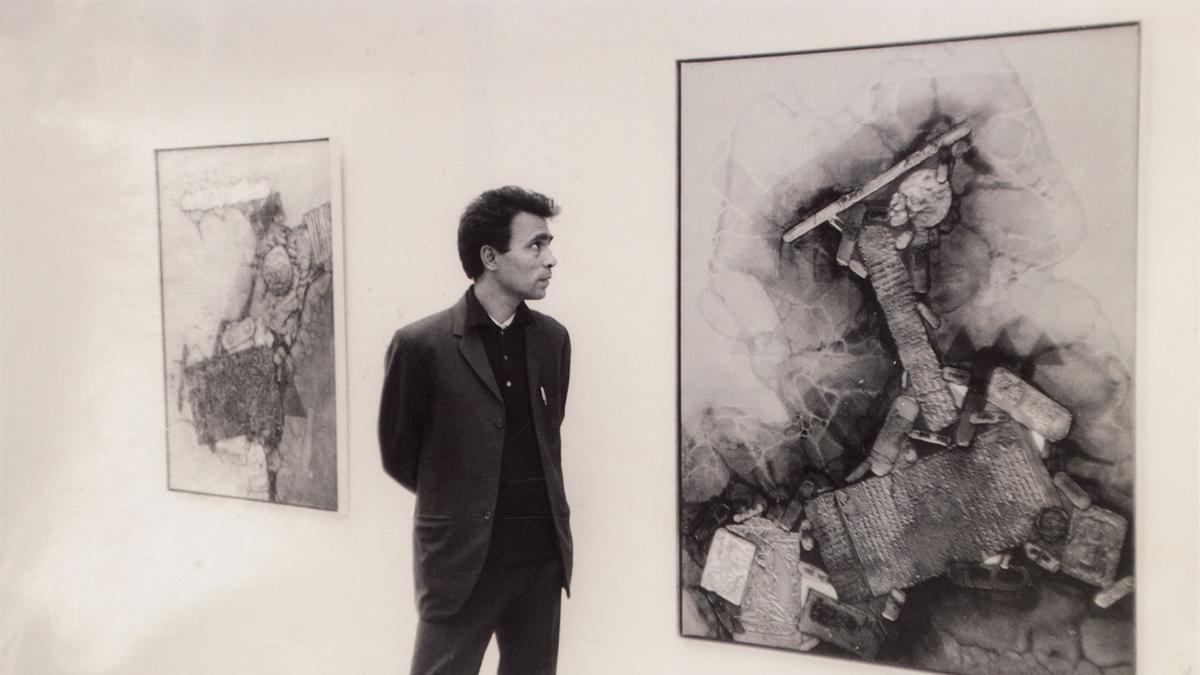

Perhaps Bombay/Mumbai is the only city that is so obviously the product of circumstance rather than deliberation. That said, it is also the most reshaped. In its more than 300-year history as a rising littoral to mercantile to global city, there have been as many misses as there have been hits. Architect and civic historian Robert Stephens’ (37) compilation of the unrealised projects that could have shaped Mumbai, Bombay Imagined: An Illustrated History of the Unbuilt City, is the latest addition to the literature on the city’s development, and perhaps one of the most significant.

Robert Stephens

| Photo Credit: Tina Nandi

The American — one of the latest in a long, happy tradition, to come from outside the city (in 2006) and to make it his own — has rigorously and resourcefully prised out more than 200 imaginations of Mumbai from, in his words, “two dozen institutions on three continents”. These include reclamation plans, infrastructural overlays, monumental architecture, airports, and even more airports. All came to naught, but still tell us of the city, of the time they were proposed in, and allow us some wishful speculation. In doing this, the principal architect at RMA Architects has also brought to light some figures from its past who deserve a better place in the canons of historical personages that shaped Mumbai. Edited excerpts from an interview:

How do you assess the relevance of archiving the unbuilt in the historiography of a city’s development?

As a kid in school, I loved tug-of-war, despite the fact that our team almost always lost. I like to think of the city’s built environment as the byproduct of an urban tug-of-war. Traditionally, in the built history of most cities, one sees and hears about the victors. Those who were lucky enough to have their dreams translated into reality take the cake of historiography. But for every scheme that was built, there were one or two or three or a dozen alternate ideas challenging one another, each with unique and often relevant arguments for their existence. By rewinding and exploring the city through those seminal moments of struggle we glean insights into the very marrow from which our city’s form, perhaps one could even say her very soul, was crafted.

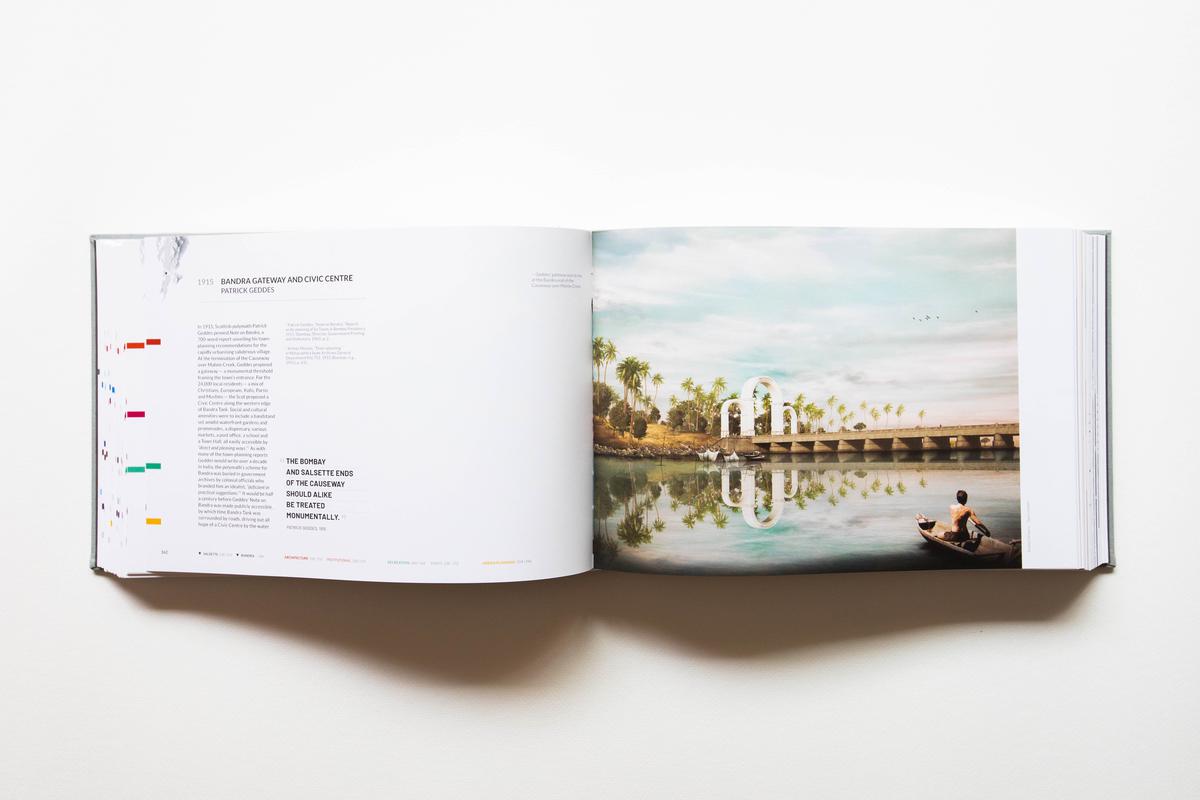

The Bandra Gateway and Civic Centre proposed by Scottish polymath, Patrick Geddes, in 1915

| Photo Credit: Tina Nandi

Once you got into the momentum of gathering stories of unrealised projects in Mumbai, how far did you have to cast your net to gather together this extensive archive?

After 15 years in the city, I am convinced that word of mouth is the best way to get anything done in Bombay. If you need a tailor, you ask a neighbour for a recommendation. If you need a good broker for finding an apartment, you ask a friend. The same principle proved to be true in archival research. If you need to discover those who imagined a transformed city, ask those you already know. For example, although I never met Charles Correa, I knew about his extensive work on the city, leading me to seek out as much material referencing him as I could find. In an interview in 1986, Correa unveiled Le Corbusier’s failed dream to design the Air India Tower at Nariman Point. He exclaimed:

‘[Le Corbusier] asked Mr. Tata, but Mr. Tata refused. He turned down the greatest architect of the century and instead employed a rotten third-rate firm from Chicago to design the building. Can you imagine if Corbusier, at the height of his power, had designed that building? … Ten or 20 other people driving down Marine Drive would have been inspired to create a building like that. It would have changed our city.’ Regardless of the century in which they lived and worked, Bombay’s creative residents have consistently loved to reference those whom they both admire and despise. Word of mouth, even from those whose voices have long been silent in the grave, proved to be the most fruitful form of research in creating the Bombay Imagined archive, a collection which draws material from nearly two dozen institutions on three continents.

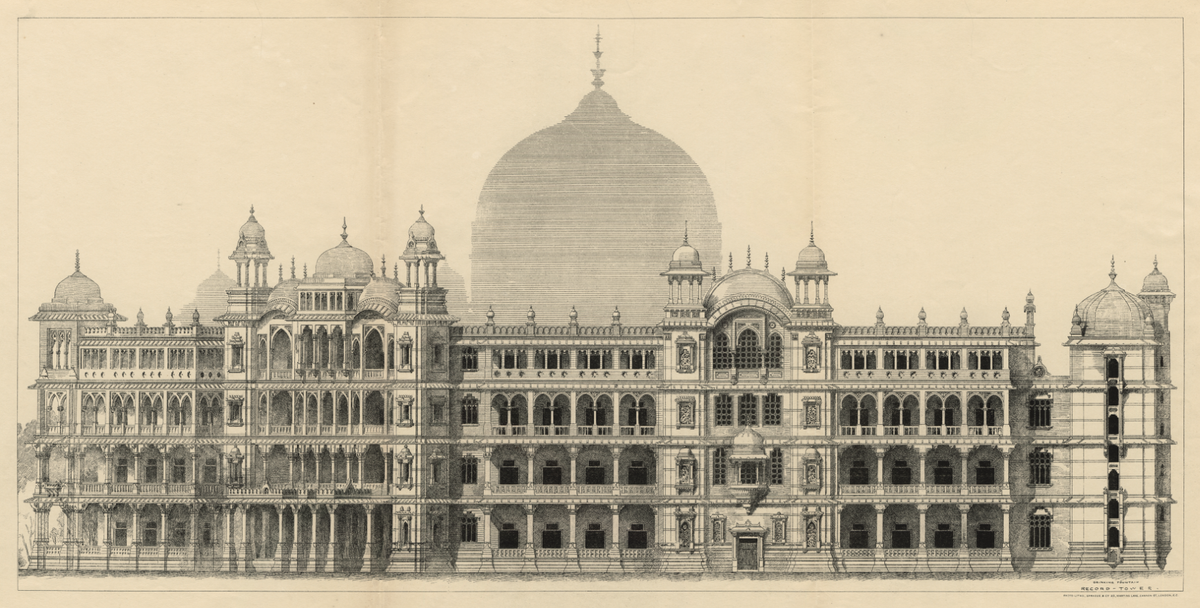

The elevation of Chisholm’s proposed Indo-Saracenic design as seen from Hornby Road

| Photo Credit: Urbs Indis Library

You have dedicated this book to William Walker. He is, as yet, an unknown figure in the history of Bombay’s urban development.

I like to think of William Walker as one of the earliest environmentally-minded citizen-activists in Bombay’s history. He moved to the city in 1845, at the age of 45, and stayed for 20 years. Under the pseudonym of Tom Cringle, Walker penned dozens of dreamy articles which were published in local newspapers, pointing his fellow citizens to a future Bombay that was more thoughtful, more efficient, and in many ways, more kind.

I like to think of William Walker as one of the earliest environmentally-minded citizen-activists in Bombay’s history. He proposed to light street lamps with gas captured during the cremation of Bombay’s deceased, and envisioned an open-air quarry prison where convicts could work towards restructuring society with a rock solid foundation.

Walker opposed the Back Bay Reclamation Scheme [arguing instead that the very centre of commercial gravity should shift towards the centre of the island where empty land already existed], and in its place proposed that the rocky foreshore should be transformed into a lush pedestrian promenade. Walker proposed to light street lamps with gas captured during the cremation of Bombay’s deceased [a gesture he deemed deeply symbolic… even in the darkness of death one exudes a bright light!], and he envisioned an open-air quarry prison on the mainland, where convicts could work towards restructuring society with a rock solid foundation [literally]. Towards the end of his tenure in Bombay, Walker compiled his articles into a self-published book and gifted one copy to Governor Bartle Frere, perhaps in a final effort to advocate for the city he loved, but knew could be greater.

The forested hillside zoo on Chowpatty Cliff was to overlook the industrial landscape of Central Bombay

| Photo Credit: Aniket Umaria | Speculation

You commissioned around 30 works of ‘speculative art’, visions of projects in the book that had no visual documentation. How rigorous were you in doing this?

During the course of research, I would often come across plans that were expounded upon with great literary prowess. So evocative were the written descriptions that I could see the scheme in my mind, despite the fact that there was no known surviving drawing to illustrate the scheme. What began as a disappointing absence [because I was clear that every failed plan was to be supported by a visual] transformed into an exciting opportunity when we decided to create speculations. The basic aspiration of each speculation was to recreate the city at a given point in time with precision using archival maps and historical data, and then into that newly-created context embed the imagined. In the space between these two essentially quantitative layers [the known historical and the unseen imagined], we let the imagination fly. The tone of the sky, the tilt of trees, the setting of the sun and other forever-unknowns, these are where the artistic complemented the historic.

Which projects, in your opinion, would have resulted in a Bombay substantially different from the one we find ourselves in?

Out of the 200 unrealised visions that comprise Bombay Imagined, there are about a dozen which would have rendered the city unrecognisable from its 21st-century form. In 1720, the East India Company’s Captain Johnson devised a scheme to cut a 30-metre-wide laceration across the city’s landmass from Mahalaxmi to Mazagon. The salt-water channel was to function like a funnel, allowing the Arabian Sea to flow through, rather than over the city during the seasonal monsoon. Just imagine, if Johnson’s slice had been served, and succeeded, more cuts might have followed and Bombay would have transformed into a Venice-like environment, a flood-free city of monsoon-regulating canals.

The Great Channel was to function like a funnel, allowing sea water to traverse through, rather than over, Bombay’s latent landmass

| Photo Credit: Aniket Umaria and Fauwaz Khan | Speculation

Do you think the physical history of Bombay/Mumbai is a history of lost opportunities?

Sometimes, while trudging my way through Mumbai’s convoluted environment I like to dreamstorm: what if many of the utopian, altruistic plans from Bombay’s past had come to fruition? If [engineer] PG Patankar’s Underground Railway of 1969 had been built, perhaps my daily commute in the local train would not be the equivalent of a full body massage? Or, even more radically, if [journalist] Ajit Bhattacharjea’s proposal to ban private vehicles in the Island City in 1973 had been realised, then maybe I could enter into my dreamy destiny of being a pedestrian without fear? For more than three centuries, residents of Bombay have allowed themselves to dream freely, only to awaken to a nightmarish reality that has consistently turned its back on one bold vision after another. The city of dreams is also the city of missed opportunities.

The writer is Professor of Architecture at Sir JJ College of Architecture, Mumbai.