[ad_1]

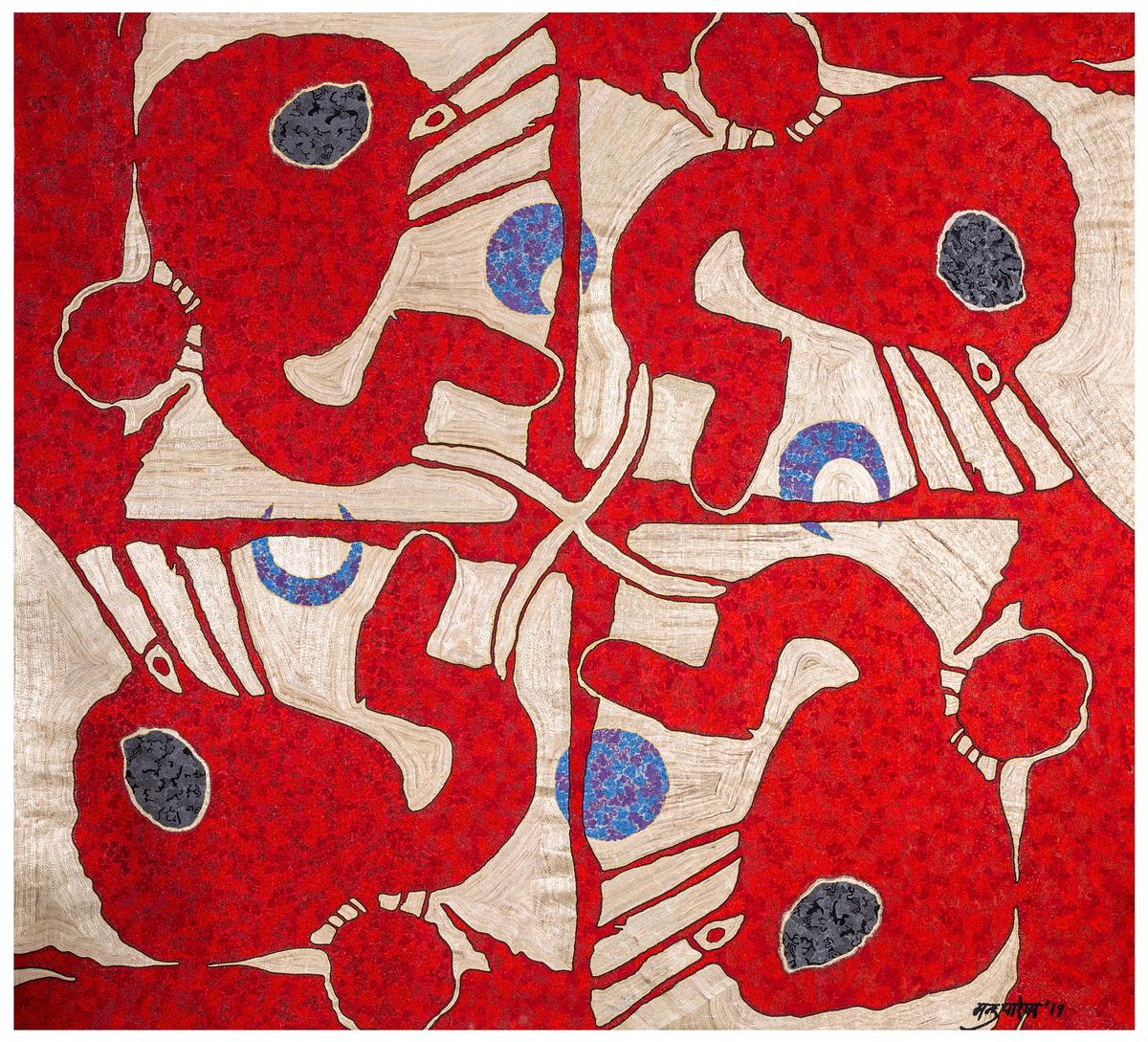

There is a fine spot in Mumbai’s industrial Snowball Studios — the site of the Mul Mathi exhibition — to quietly absorb the scale and ambition of a collaborative exercise that intersects art, craft and textiles. From there you see Manu Parekh’s original Evening Chanting glowing in the distance, while closer to your right looms the reimagined ‘textile art’ version. The latter, towering at over 11 feet, gets more profound as you inch closer to absorb the stem stitch variations that create a blend of colour and texture, with the fine needle zardozi work for sfumato effect. “The painting speaks to you. One feels the vibration of sound through the [original] painting and we wanted to ensure the same vibration came though with our threads,” explained Karishma Swali, creative director of Chanakya School of Craft.

Karishma Swali with Manu and Madhvi Parekh

| Photo Credit:

Dior / Chanakya School of Craft

Artist couple Manu and Madhvi Parekh

| Photo Credit:

Dior / Chanakya School of Craft

To Paris and back

Swali, 45, led this project of translating art works by the Delhi-based couple Manu and Madhvi Parekh as embroidered installations for Dior’s Haute Couture Spring/Summer 2022 show at Paris’ Musée Rodin. It was a quasi-retrospective of the Parekhs’ art — Manu’s spiritual abstracts and Madhvi’s impressions of folk and rural traditions – which Swali’s team of 320 artisans or karigars completed in 190 days.

The Dior Haute Couture 2022 runway

| Photo Credit:

Adrien Dirand

There were challenges, of course, of replicating movement and harmony with a needle. And of retaining the vividness of lines with the right shades and textures – only natural fibers such as jute, cotton, silk, cord and nettle, and plant dyes were used here. Chanakya’s atelier, with master craftsmen largely from Lucknow, Kolkata and Kashmir, overcame them in time and soon 3,600 sq ft of embroidered fabric was shipped off to Paris. Now a year later, under the curation of the Asia Society India Centre, 22 of these tapestries, as well as archival materials, are being showcased in Mumbai as Mul Mathi.

At Chanakya’s atelier

| Photo Credit:

Dior / Chanakya School of Craft

Blurring hierarchies

The exhibition launched a day before Dior presented its pre-fall 2023 collection at the Gateway of India, and organisers have since seen a huge turnout. They range from artists, curators and gallerists to fashion designers and students. In January last year, these floor to ceiling embroidered works of the Delhi-based Gujarati artists stood alongside Rodin’s sculptures for a week after Dior’s SS22 show, so the public could view them. For art, craft and fashion enthusiasts in India, this is a chance to see the works up close as well. “The first response is always to the scale of the works, their monumentality, but it has been most interesting to observe people spending time with each work, going close to it to see its detailing and moving back again to take it in as a whole,” remarked Ketaki Varma, Associate Director, Programmes at Asia Society India Centre.

A model walks the runway during the Dior Pre-Fall 2023 show at the Gateway of India

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

In the last few years, Dior and its first female creative director, Maria Grazia Chiuri, have entrusted the creation of monumental works for their défilés to Chanakya. It has resulted in collaborations with artists Judy Chicago, Eva Jospin and Kyiv’s Olesia Trofymenko. For Chiuri, who shares a 25-year relationship with the atelier and Swali, this exhibition (there was also a Dior retrospective at Chanakya earlier this month) takes people “behind that 10-minute fashion presentation or the picture they see in the news”.

Karishma Swali (left), creative director of Chanakya School of Craft; and Dior’s creative director Maria Grazia

| Photo Credit:

Dior / Chanakya School of Craft

“The House of Dior was an enabler of this experiment, while Karishma has been the laboratory, a library, and an archive,” Radha Mahendru, Director of Strategic Partnerships and Development at the Asia Society India Centre noted at the show’s launch party. While the exhibition brings together art, craft, design and fashion in an attempt to blur the hierarchies that exist between them, it has raised interesting questions. Why can’t fashion, craft and art collaborate without having to become the other and yet inform the other, was one. This is one successful model, are there others? And why did it have to take a Dior to make this possible, in a large country with many benefactors?

At Chanakya’s atelier

| Photo Credit:

Dior / Chanakya School of Craft

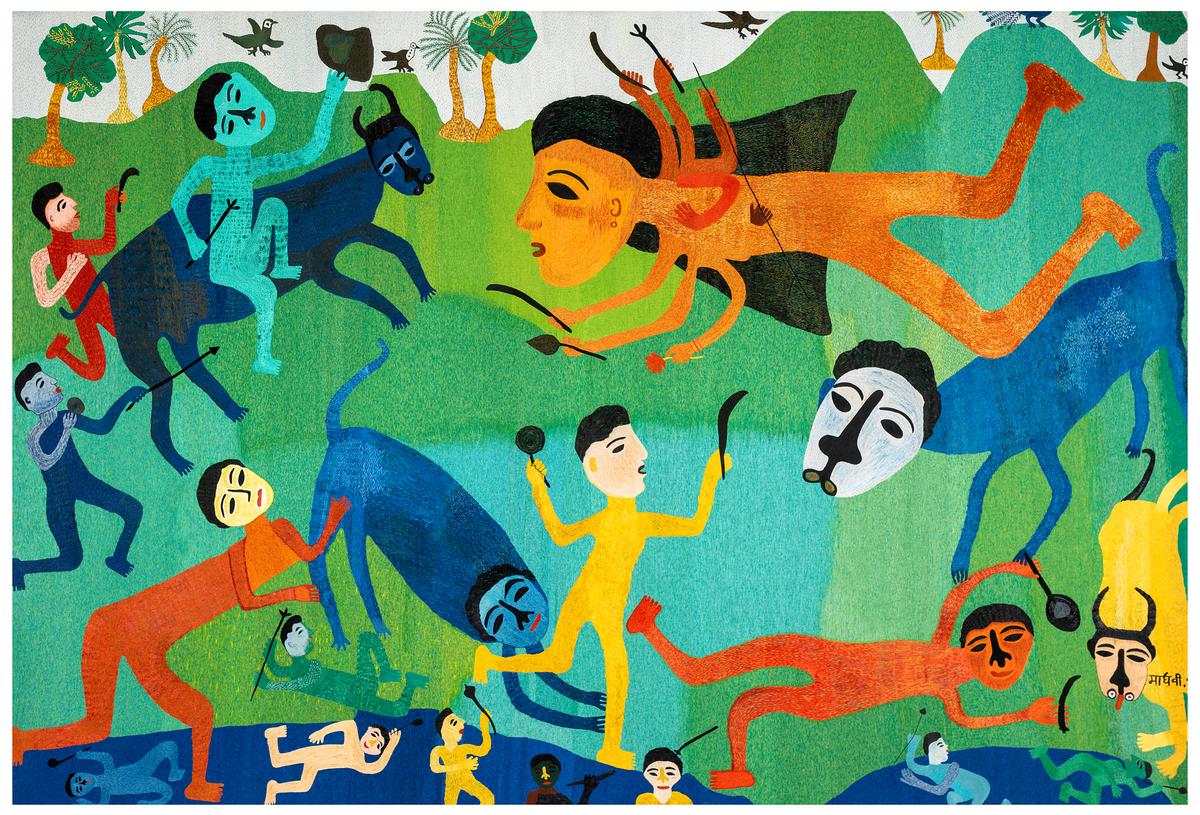

Mixed media hand embroidered panels with twisted chain stitch, stem stitch, and feather stitch techniques to highlight the strokes and lines in the drawing by Madhvi Parekh

| Photo Credit:

Pramod Kadam

At the show opening, as Mumbai and Delhi’s art and fashion worlds mingled, and cocktails like the Diorama featuring gin, rose, Campari and sparkling made the rounds, many seemed to agree that the true star of the collaboration was Swali. “You can really appreciate the creative collaboration when you see a brush stroke [from the original painting] scaled up 10 times, the texture of oil paints translated to thread work. How do you make that leap? The craftsmen need that provocation so they can break that ‘Lakshman Rekha’. And that provocation is what Karishma Swali offers,” Mahendra observed.

Madhvi Parekh in front of one of her ‘translated’ paintings

| Photo Credit:

Dior / Chanakya School of Craft

“You can really appreciate the creative collaboration when you see a brush stroke from the original painting, scaled up 10 times, and the texture of oil paints translated to thread work. ”Radha MahendruDirector of Strategic Partnerships and Development at the Asia Society India Centre

Self-alignment and the Parekhs

Away from the crowds, in the studio’s hushed lounge, we found Swali taking a coffee break with the artist couple, both in their 80s. “We deeply enjoy being together,” she explained. “It never feels like work. When I go to their home, I get to eat [Madhvi’s] incredible food and take an afternoon nap. When you are able to work from that space, it allows you to be led. I hope one can feel that with this show.” She added that there was a deep connect with their work. “And self-alignment, a lesson that craft teaches us. For craft is about riyaz and practice.”

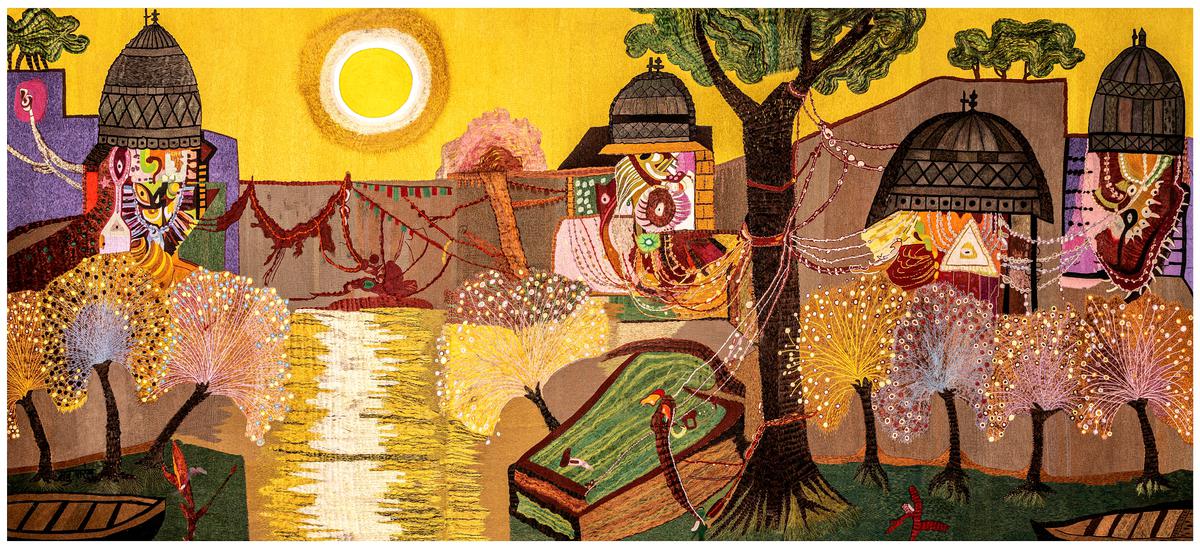

Chanting Sutra, featuring knotting variations and saddle stitch to reflect movement

| Photo Credit:

Dior / Chanakya School of Craft

Evening in Banaras

| Photo Credit:

Dior / Chanakya School of Craft

Self-alignment is a term Swali uses often, even when talking about the Chanakya School of Craft she founded with Dior’s Chiuri in 2016. About the Parekhs, she added that she appreciated how their work was reflective of her Indian roots but in a more contemporary way. Manu likened the exercise to the translation of an English novel to German. “My medium is colours and the brush, hers is threads. But when translated, there was perfection,” he said. Perhaps his early stint with the Weavers’ Service Centre where he worked on craft and textiles under the mentorship of cultural giant Pupul Jayakar prepared him for this project. “Like with this team, I was the only male in that group. I’m full of life due to this understanding, and don’t have an ego,” he gently joked.

(L to R) Inakshi Sobti, Maria Grazia Chiuri, Manu and Madhvi Parekh, and Karishma Swali

| Photo Credit:

Dior / Chanakya School of Craft

Madhvi, whose 1971 World of Kali — featuring the armed goddess against folk iconography — was was just as magnificent in its embroidered avatar, smiled. Then reminded us in Hindi about the strength of women and feminine energy. Incidentally, these themes are close to Chiuri’s heart as well, as she attempts to bridge feminism and fashion in her Dior collections.

The Chanakya School of Craft has educated 1,000 women to date and Mul Mathi includes framed samples from some students, almost like miniature paintings. “This goes beyond a vocational training programme for them, it is both a means of creative expression and financial freedom,” said Swali of the students aged between 18 and 61.

At the Chanakya School of Craft atelier

| Photo Credit:

Dior / Chanakya School of Craft

Working behind the scenes

Mul Mathi is a reminder that while one must honour and celebrate the source, each collaborator is essential. Exhibition designer Reha Sodhi, who had about 72 hours to set it up, from the false walls with metal reinforcements to the framing of the works on site — they were too large for trucks. Mayank Mansingh Kaul and Ritu Sethi, members of Asia Society India Centre’s advisory council, who helped with the reading room’s rare art, craft, textile and fashion books. And the curators who have created an immersive experience with this craft meets art model.

Mul Mathi at Chanakya

| Photo Credit:

Sahiba Chawdhary

CEO Inakshi Sobti summed it best at the event, “We hope this exhibition brings up critical questions around labour, collective work, the status of crafts in Indian society, and the possibilities offered by collaboration and patronage in their preservation.” In a country with millions of karigars, and just a handful of ateliers like Chanakya that offer fair pay and benefits, it is time for some answers.

Mul Mathi, free entry, is at Snowball Studios till April 22. A panel discussion on collaborative infrastructures for craft is on April 19.

A worthy translation

Such reimagination is only possible through hand embroidery, says independent textile curator Mayank Mansingh Kaul

The biggest impact of the Mul Mathi showcase according to you?

The kind of reimagination of the original paper and canvas works by artists Madhavi and Manu Parekh can only be done at the scale which has been attempted here, through hand embroidery. It would be tremendously challenging in handweaving, handpainting or block printing. From such perspectives, it is relevant to view the works on display as conveying the capacity for innovation in stitches and in surface embellishment. I think its biggest impact is to provide the lens of excellence and collaboration in hand artistry, which has for far too long primarily be seen through the prism of craft as a source of livelihood.

The country’s artisanal history has inspired designers across the globe. Do you believe this acknowledgement and couture diplomacy by Dior and Maria Grazia Chiuri will encourage other international houses to come forward and do the same?

I certainly hope so. I think it is important that we expect more of this from Indian designers as well — they often borrow freely from India’s collective design repertories without giving credit where it is due.

Karishma Swali and Maria Grazia Chiuri

| Photo Credit:

Sahiba Chawdhary

Chanakya retrospective

| Photo Credit:

Sahiba Chawdhary

Chanakya retrospective

| Photo Credit:

Sahiba Chawdhary

What do you make of the criticism that this acknowledgement comes too late, after decades of an extractive relationship between Dior and Indian artisans?

The debate is crucial, and because its components form an integral part of my own practice as a curator of Indian textiles I think that some of this criticism needs to be turned inwards – how do Indian designers who make the ‘international’ leap get away with using the same tropes of Indian exotification that we blame Western brands for? Why are we still comfortable with the hierarchies which exist between Indian artists, designers and craftspeople?

The independent textile curator is also a member of the Arts Advisory Council for South Asia at the Asia Society

Power of the source

In addition to Dior, Chanakya International, launched in 1986, by Vinod Shah, works with fashion houses Fendi, Valentino, Versace, Moschino and others. Swali, who heads operations with her brother Nehal Shah, also runs Jade, specialising in Indian bridal, with her sister-in-law Monica Shah. In 2021, she launched a contemporary line, Moonray, with her 16-year-old daughter, Avantika. Fluent in Italian — “I learnt it on my first work trip at 18, when assisting my brother” — and partial to sculptures, she talks about the school she founded with Maria Grazia Chiuri in 2016 and the process of self-alignment:

You have said that that the Chanakya School of Craft is part of a preservation exercise.

It started as a very simple thought. I had already been in craft for many years and had seen some precious crafts go out of circulation. I realised that in India craft had never really been institutionalised, but is taught generationally from father to son. So we felt this great responsibility to find a beginning into the preservation exercise. It’s something I discussed with Maria Grazia early on. We discussed the importance of innovation, education and keeping craft relevant. It was her idea then to dedicate the school to women.

The Tree of Life or kalpavriksha in zari

| Photo Credit:

Dior / Chanakya School of Craft

The Parekhs’ art showcased as Mul Mathi must have been an interesting departure from working with garments and bags for international fashion houses.

When we do an artistic collaboration, it is a sharing of the creative space. They bring their art and we bring on board the ability to curate and interpret their art with our craft. We realised that when you stand for something collectively, it is more amplified. It is something I enjoy tremendously and when you have a canvas that is larger than life, you are able to immerse yourself and follow an instinct. The process is a self-alignment and there was growth for all of us.

Madhvi’s paintings have so much freedom in her lines and we wanted to reflect that through our lines and techniques. And Manu Parekh’s canvases vibrate with energy. It was a very personal dialogue with craft and approached sensitively. Evening Chanting, for instance, took 54,600 hours to create.

Mul Mathi at Chanakya

| Photo Credit:

Sahiba Chawdhary

How has Maria Grazia Chiuri powered the Chanakya story?

She champions crafts around the world and carries people with her always. I am tremendously inspired and to work on this aligned vision with her. She is open with our students, wanting to hear their stories. It’s personal for her as well and I am incredibly fortunate to have that energy and larger vision that allows us to dream bigger.

Dior x Chanakya retrospective

| Photo Credit:

Sahiba Chawdhary

Dior x Chanakya retrospective

| Photo Credit:

Sahiba Chawdhary

Your grandfather collected valuable works of art. Did any of it make a huge impact on you?

I remember being moved by stone sculptures as a child. And the understanding that they have been around for centuries. Sometimes there is an intangible value to tangible objects and I appreciate that. It is the same intangibility that moves me about craft. I have a stone sculpture of Adinath bhagvan [the first of the 24 Tirthankaras of Jainism], about 2.5 feet, and it is special to me.

What is the afterlife of the 22 art works at Mul Mathi?

Eleven belong to the Dior foundation and their museum, and 11 to our foundation. In India, we want like-minded people to support our foundation and through these build a corpus to take Chankaya School to other parts of India as well. And perhaps build some global connections to integrate craft and design.

[ad_2]

Source link