[ad_1]

It’s not often that you walk into an art exhibition and are greeted with tasting stations of ker ka achaar, rabodi and mangodi — instead of the usual wine and cheese. Ker, guests found out, is a desert berry, the papad-like rabodi is made with maize flour, yoghurt and spices (often cooked as a sabzi when fresh vegetables are in short supply), and mangodi is a condiment made of sun-dried ground lentils.

Researcher Dipali Khandelwal’s pop-up museum at the Jodhpur Arts Week was immersive. “We document Rajasthan’s disappearing food cultures from the lens of climate, nature, agriculture, communities, art and culture,” the founder of The Kindness Meal shared. “We celebrate the art of foraging, food preservation techniques, culinary practices of our ancestors, and family recipes.”

“Whose Heritage Is it?” installation

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Public Arts Trust of India

Jodhpur Arts Week, which debuted between October 15 and 21, stood out for its efforts to give public and community-based art the sort of dignity and visibility they deserve but rarely get. Rajasthani artisans practising generational crafts, and children from government schools — who participated in an immersive creative arts education programme — showcased their work alongside international artists.

Erez Nevi Pana’s Inside Out explores the relationship between native species and invasive plants in the Thar desert

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Public Arts Trust of India

Jodhpur as inspiration and canvas

Art galleries, which tend to present themselves as exclusive spaces because of the social capital required to enter them, were ditched in favour of more welcoming public locations in the heart of the walled city: Ghanta Ghar (a clock tower built by Maharaja Sardar Singh), the heritage premises of Shree Sumer School, and Toorji Ka Jhalra. The last destination — an 18th century stepwell commissioned by Maharani Tanwar Ji (wife of Maharaja Abhai Singh, who brought Jodhpur back under the direct rule of the Rathores after the death of Mughal emperor Aurangzeb) to provide water in the harsh summers — has become a vibrant gathering place for people across socio-economic groups to play, swim, read, socialise, and make Instagram reels.

During the week, Mimansha Charan, a Jodhpur-based writer and researcher specialising in local history, led curated walks to develop appreciation for “the historical and cultural significance of these venues”, and acquaint attendees with charpai weavers, lac bangle makers, bamboo weavers, and silver jewellery makers. “They are not only custodians of traditional skills, but also entrepreneurs who run workshops that double up as outlets,” she said. Some of them were also invited to conduct workshops at Jodhpur Arts Week.

Heritage walks in the Walled City

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Public Arts Trust of India

The event featured both established and emerging artists. Site-specific installations by British visual artist Liz West and generative artist Ujjwal Agarwal invited guests to look at familiar landmarks in a new light, witnessing the possibilities that arise from the interaction of modern technology with traditional architecture. West’s Tiered Reflections, for instance, took inspiration from the architecture of Toorji Ka Jhalra, especially its dramatic geometric steps, and colours that blend in with the vibrant atmosphere of the surrounding bazaar. Agarwal turned the ancient clock tower into a living canvas, with a responsive clock at its centre. His Timelines was an exploration of art, time, and technology.

Liz West’s Tiered Reflections

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Public Arts Trust of India

Ujjwal Agarwal’s Timelines

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Public Arts Trust of India

Elsewhere, London-based artist Hetain Patel’s video works, Do Not Look at the Finger and Mussalman, dealt with identities built around gender and race through ritual, body painting, and choreography. And interdisciplinary artist Kiran Kumar — who worked with students at the Indian Institute of Technology in Jodhpur — put together a multi-sensory exploration of the city’s architecture, combining his interest in algebraic polynomials with a range of materials, including paper, fabric, metal, clay, and wood.

‘Creation, conservation and cooperation’

The arts week was an initiative by Public Arts Trust of India (PATI), a two-year-old platform set up by Sana Rezwan, its founding chairwoman, to democratise access to arts and culture. “Jodhpur’s rich cultural heritage, architecture, and vibrant handicraft industry make it a significant creative destination. It’s the centre of India’s $200 million handicraft industry,” says Rezwan. “Expanding to Jodhpur allowed us to build on PATI’s work in Jaipur, where Jaipur Art Week has grown into an incubator for early-career artists.”

Sana Rezwan

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Public Arts Trust of India

PATI also collaborated with Jaipur Rugs to exhibit the work of Rajasthani artisan Maina Devi, the first Indian finalist (2023) of the Loewe Foundation’s prestigious Craft Prize. Going forward, it will support artisans based in Jodhpur and Jaipur who are keen to apply for the prize, which gets the winner €50,000. “Our partnership with the Loewe Foundation focuses on amplifying the representation of Indian artisans in the Craft Prize. Historically, barriers like language and limited internet access made it challenging for many to apply,” says Rezwan. “PATI’s team has been bridging this gap by translating and sharing information, guiding artisans through the application process.”

Yarn spinning workshop with Maina Devi and her husband Shishupal Khatik

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Public Arts Trust of India

Her chief accomplice is Emma Sumner, director of PATI, who has worked with the U.K.-based arts organisation Grizedale Arts, conducted research with Somaiya Kala Vidya in Kutch, and developed projects with female artisans in Ahmedabad. “Creation, conservation and cooperation are the three most important pillars of our work,” says Sumner. “It is important for us to build relationships that are strong and meaningful so that engagement with the arts is not limited to one week but happens all through the year.” They conduct residencies and bring arts education to children who, previously, had no access to the arts.

Emma Sumner

| Photo Credit:

Richard Tymon

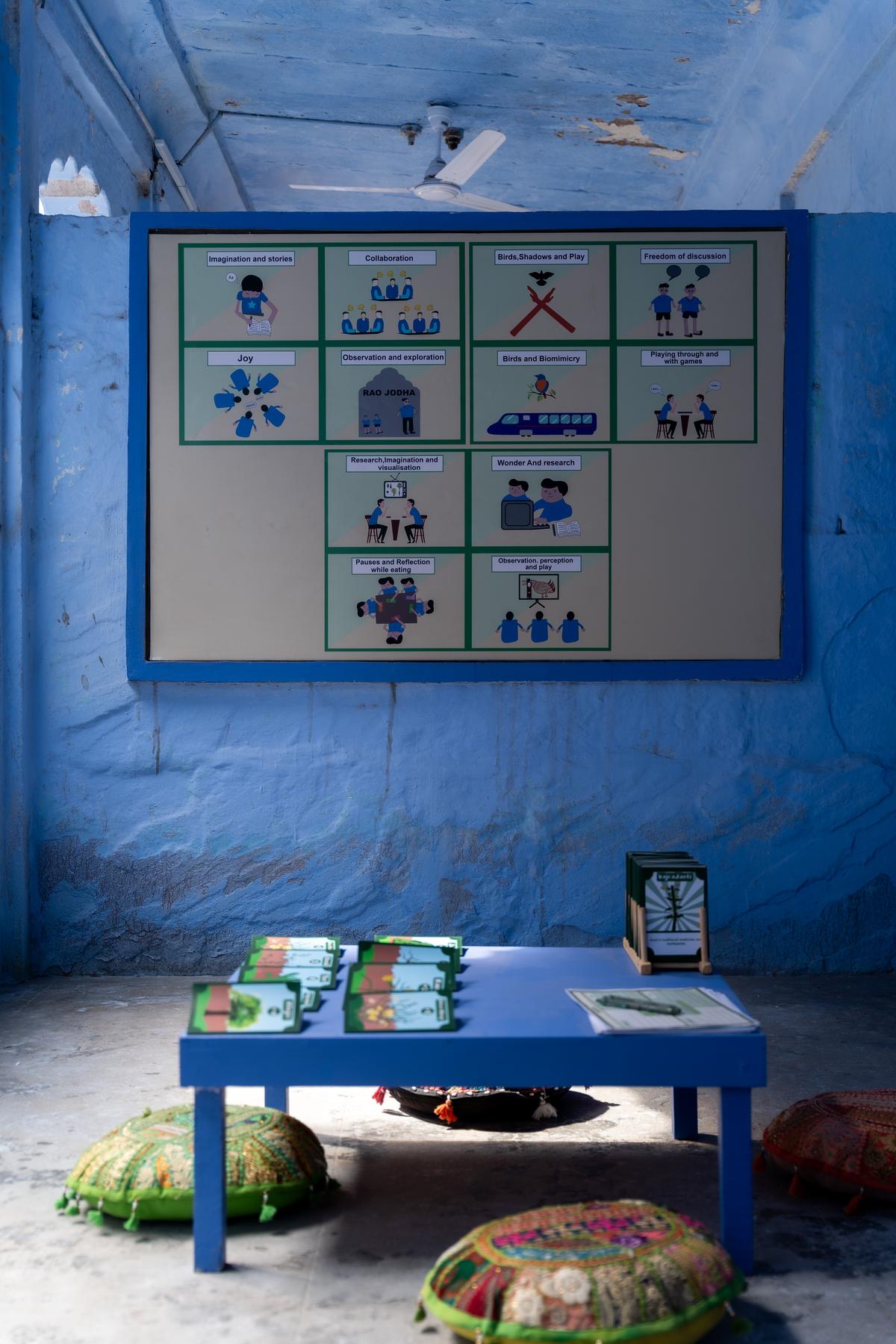

For example, PATI collaborated with educator Kriti Sood’s pedagogical research lab, Learning through Arts Narrative and Discourse (LAND), to help teaching fellows develop and pilot an arts curriculum in five government schools. An experiment that came out of it involved children at one of the schools ideating and designing card and board games based on the principles of biomimicry (the practice of learning from nature’s design processes to solve problems faced by humans).

Khel Khel Mein, part of PATI x LAND Creative Arts Education programme

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Public Arts Trust of India

This gave them an opportunity to reflect on challenges such as extreme heat, water scarcity and food shortages in Rajasthan, and to exhibit their creations at the arts week.

The writer is a Mumbai-based journalist and educator.

Published – November 08, 2024 10:09 am IST

[ad_2]

Source link