Last September, fashion designer Jenjum Gadi briefly stepped away from clothes. He dipped into an alternate creative outlet, instead — that of sculpture. He took inspiration from his mother’s garden back home in Arunachal Pradesh for Apase, an exhibition featuring brass fruits and vegetables.

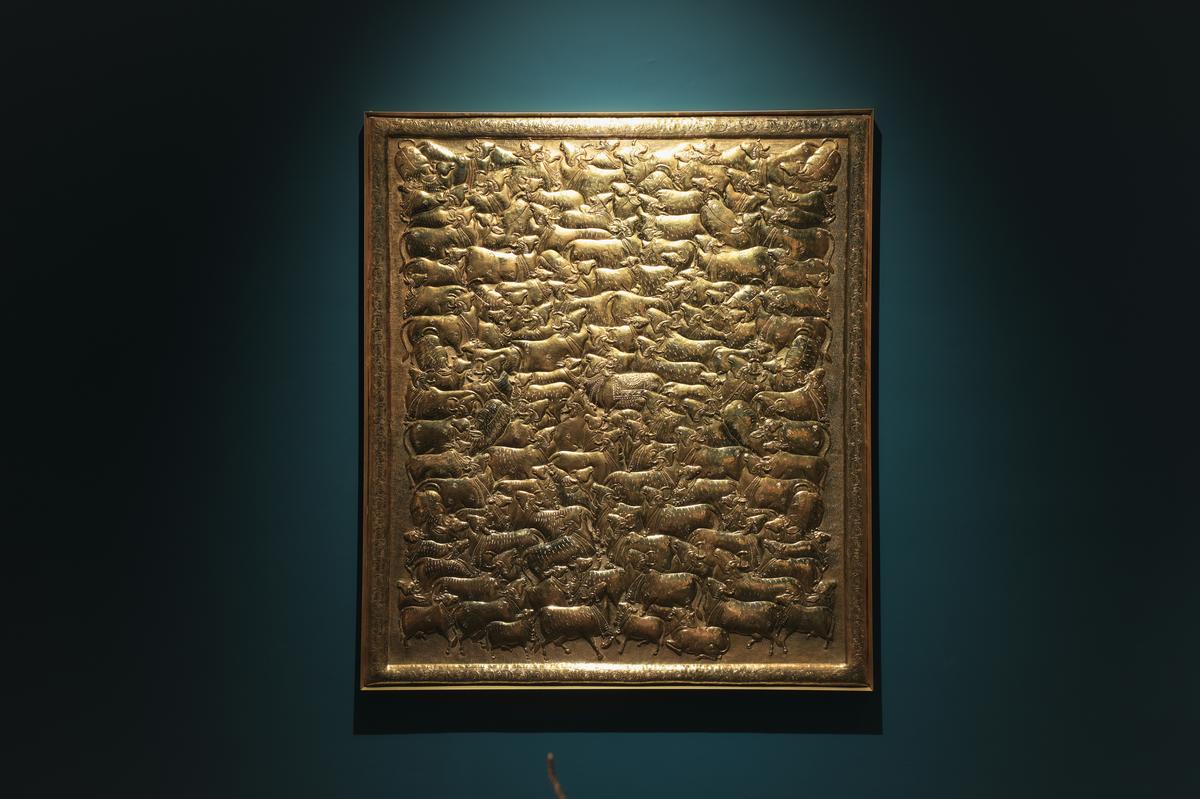

With its resounding success, Gadi secured a space for himself in the world of art. And now, he’s building his reputation with another exhibit of brass sculptures, titled Transcendent Memories. An extension of his debut, the show uses ancient repoussé and chasing techniques to create intricate pichwai motifs.

Jenjum Gadi

“Transcendent Memories continues to reflect on my childhood, just like Apase did,” he says, explaining how they are expressions of his connection with nature. “Growing up in the Northeast, I spent all my free time in the jungle collecting wild fruits and hunting birds.” When he came to Delhi to study, he was exposed to different kinds of art and culture as the city “is the centre of multicultural experiences”. But he was most drawn to pichwai. “It evoked a certain kind of emotion and memory, and I had an instant spiritual connection with it,” Gadi shares. “If you see pichwai paintings, you’ll see how rich in storytelling they are, and how deeply they are rooted in the divine through nature. That is something that resonates with me, too. They remind me of my home, and I have used their motifs to give a new meaning to everyday objects.”

From silver to brass

It all started with a bowl, Gadi says, talking about the lone silver piece in the collection. “My mother got it from a small shop in a remote part of Arunachal Pradesh, next to the China border. I found it intricate and interesting, but when I went to meet the craftsman, he didn’t entertain me. His assistant took my number and contacted me three months later. Initially, I wanted to make silver jewellery, but there were complications. So, instead, I decided to make brass models.”

Sculptures have provided the designer with a new medium to explore memory, spirituality, and tradition. And while he may have over 15 years of experience in designing clothes, working with metal has been a learning process. “The thought process is quite similar — both are about detail, texture, and storytelling,” he says. “With sculpture, you have to be more meticulous because if something goes wrong, it’s very difficult to correct it. Fabrics are easier to deal with, but metals are ambitious and an expensive affair.”

Intersection of art and fashion

Gadi’s dive into art isn’t an isolated happenstance. Today, several fashion designers are exploring beyond fabric. Earlier this year, Tarun Tahiliani showed The Tree of Life — a series of eight tapestries exploring the relationship between humans and nature, using painting and techniques such as French knots, aari embroidery, and mother-of-pearl detailing — at the India Art Fair.

Last October, David Abraham and Rakesh Thakore, the duo behind the respected fashion brand Abraham & Thakore, lent the walls of their flagship store in New Delhi to exhibit 18 stunning canvases by Mangala Bai Marawi’s Baiga body art. Marawai is an indigenous artist from Madhya Pradesh and one of the few remaining badnin (women tattoo artists) in her community who are committed to preserve and share the Baiga tattoo art form. By making space for this ancient practice, A&T championed the intersection of fashion and indigenous art — which they have often looked to for inspiration. And let’s not forget how, in 2019, Raw Mango’s Sanjay Garg commemorated 10 years of his brand with a series of collectibles.

“If you are a creative person, you’re an artist. And you’re always looking for a different avenue to express yourself; sometimes clothing alone isn’t enough to express what we want to say,” explains Gadi. “Art gives us the freedom to go deeper, to slow down, and to connect with our roots in a different way. Moreover, the art scene is very experimental right now, and this is opening up the avenue for designers because lots of them are playing with mixed media to find an expression.”

“I have always loved working with my hands whether it is embroidery and now, sculpting. After years in fashion, I felt a strong need to express myself in a more personal and reflective way. Sculpture gave me a new medium to explore memory, spirituality, and tradition in a deeper form.”Jenjum Gadi

Mumbai, memory and nature

With a team of skilled metal artisans — specialised in making artworks for monasteries — flown in from the Northeast, Gadi’s sculptural endeavours have only begun. “It is always a challenge to translate something personal into a traditional craft, but we have built a great understanding. I guide my team, and they too are learning and understanding the importance of creating high quality art. It usually starts with a memory or a feeling I want to express. I work closely with the craftsmen to cast the objects in brass, and then we inscribe each one by hand with motifs that connect to my roots and inspiration. It’s a slow, detailed process that involves sketching, moulding, casting, and finishing,” he says. “I’m also conscious of the skill and labour that goes into it and therefore, we work on a ‘price per piece’ basis [unlike my tailors who are salaried].”

Gadi is already planning his next show, this time in Mumbai. “The coordination is ongoing. Hopefully, we’ll be able to make it happen later this year. I’m still developing the concept, but it will continue to explore memory and nature — and maybe experiment with a few new materials and forms. It’s going to be a more intimate presentation,” he concludes.

The independent writer is Delhi-based.

Published – April 04, 2025 10:28 am IST