[ad_1]

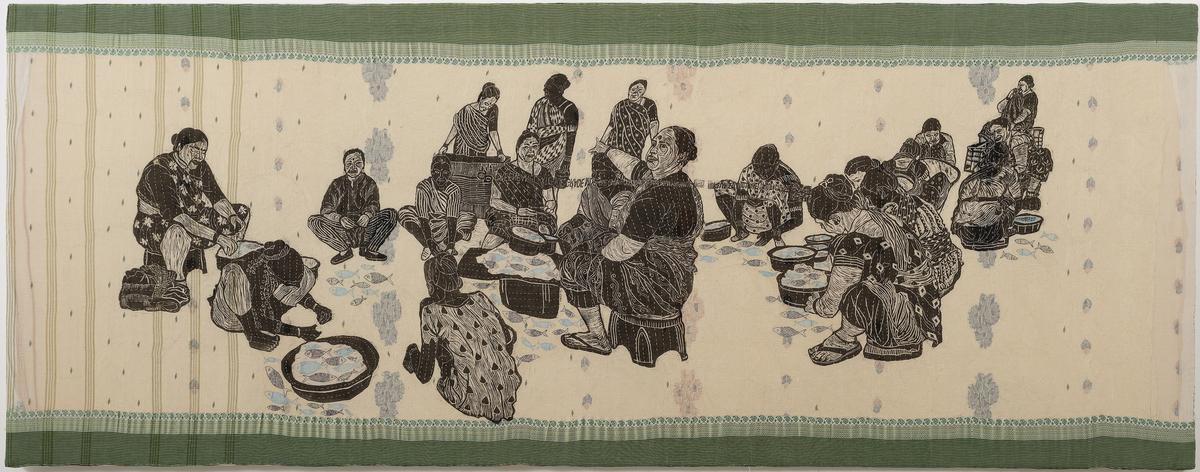

Culture, love, laughter and gossip I (2023); woodcut print and nakshi kantha on cotton saris

| Photo Credit: Courtesy Jayeeta Chatterjee and Chemould CoLab

“It’s a very Bengali thing!” laughs Jayeeta Chatterjee, 29, talking about her artistic bent of mind. “As a young child in a Bengali household, you need to either learn dancing, singing or some form of art.”

The Bengaluru-based artist found her passion in wood cut print making quite early — after an encounter with the works of veteran artist and printmaker Suranjan Das when in Class X — and chose to pursue the art form as a career. Now, after years of experience with the medium, Chatterjee is the recipient of the Asia Arts Future (India) award, at the Asia Arts Game Changer Awards this week at the India Art Fair.

Jayeeta Chatterjee

Hailing from Bolpur, West Bengal, Chatterjee studied fine arts and printmaking from Kala Bhavan in Santiniketan. And observations she made on her daily commute to and from the university led her to anchor her work in a strong element of storytelling. “I noticed the aesthetics of homes change drastically,” she recalls. “Every household object seemed to define the class or caste of the families living in that house.”

Her observations intrigued her enough to interact with the residents, and she learned, for example, that those who chose bright wall colours (much like her own home with its yellow walls) were influenced by financial factors, as vivid colours last longer. Such conversations informed her 2017 wood cut print series, Yellow Journey.

“When people share their stories with me, they’re sharing their lives and journeys. But, at times, it also gets a bit overwhelming, and I struggle with portraying the stories in the best possible way,” shares Chatterjee, who has exhibited her work at forums such as the Ulsan International Woodcut Print Art Festival, South Korea; Haugesund International Festival of Relief Printing, Norway; and most recently in 2024, at Chemould Prescott Road, Mumbai. Her solo, An Eye Inside, tracked her journey evolving from an interest in interiors and architecture to her current documentation of domestic feminine politics.

Jayeeta Chatterjee at work at the Chemould CoLab residency, 2023

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Jayeeta Chatterjee and Chemould CoLab

Wood cut prints and kantha

Chatterjee’s recent collections have focused on the lives of women in different social settings, and it nudged her to incorporate fabric in her work. “When I started documenting women, I started collecting their used saris, dupattas and even blouse pieces,” she explains, adding how she uses her phone to capture candid moments, and records short videos and snippets of conversations.

There Is No Holiday II (2023); woodcut print on recycled cotton sari, nakshi kantha

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy of Jayeeta Chatterjee and Chemould CoLab

She then began combining mediums for the first time — preparing woodblocks, printing designs on the fabric, and stitching them like a quilt, overlaid with nakshi kantha traditions. “I grew up seeing the kantha stitch in my household, but I never really paid it any attention. When I started learning the craft is when I first realised how painstaking the process is,” she says. Chatterjee learnt nakshi kantha embroidery — a style with elaborate motifs influenced by religion, culture, and the lives of the women stitching them — from artisans in Mahidapur, in West Bengal’s Birbhum district.

Her art highlights the mundane: a woman sweeping a floor, tending to a child, selling wares in a market, sorting and drying fish, or women gossiping on their haunches. As she states in the exhibition note for An Eye Inside, “These homemakers do important work and yet rarely get respect, and somehow there was resonance for me as I work at home too, and people don’t understand the work of an artist either!”

Installation view of An Eye Inside at Chemould Prescott Road

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Chemould CoLab

Story reigns supreme

Today, after years of working with nakshi kantha, Chatterjee takes little over a month to complete a single piece of art, which she stresses is actually speedy work. One of her ongoing projects is an 8×16 ft. quilt that she started work on last July, during her stint at the Hampi Art Labs residency by the JSW Foundation. The lives and stories of the women at JSW’s Bunkai Handloom Studio in Vijayanagar, Karnataka, form the subject of this massive piece.

Jibon Ghore o Baire 4 (Life at Home and Outside), 2024; woodcut print on rice paper

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Jayeeta Chatterjee and Chemould CoLab

So, what comes first for Chatterjee: the medium or the story? “The first thing I think about is the subject. I also think of representing the conversations I’ve had with people as sound waves, which I can then transfer on fabric using nakshi kantha,” says Chatterjee, given that some of the stories are too sensitive, personal or complex to simply play out loud. “If I’m working with someone, my goal is to portray that particular moment I share with them in my work.”

The writer and theatre artist is based between Bengaluru and Delhi.

Published – January 31, 2025 12:34 pm IST

[ad_2]

Source link