[ad_1]

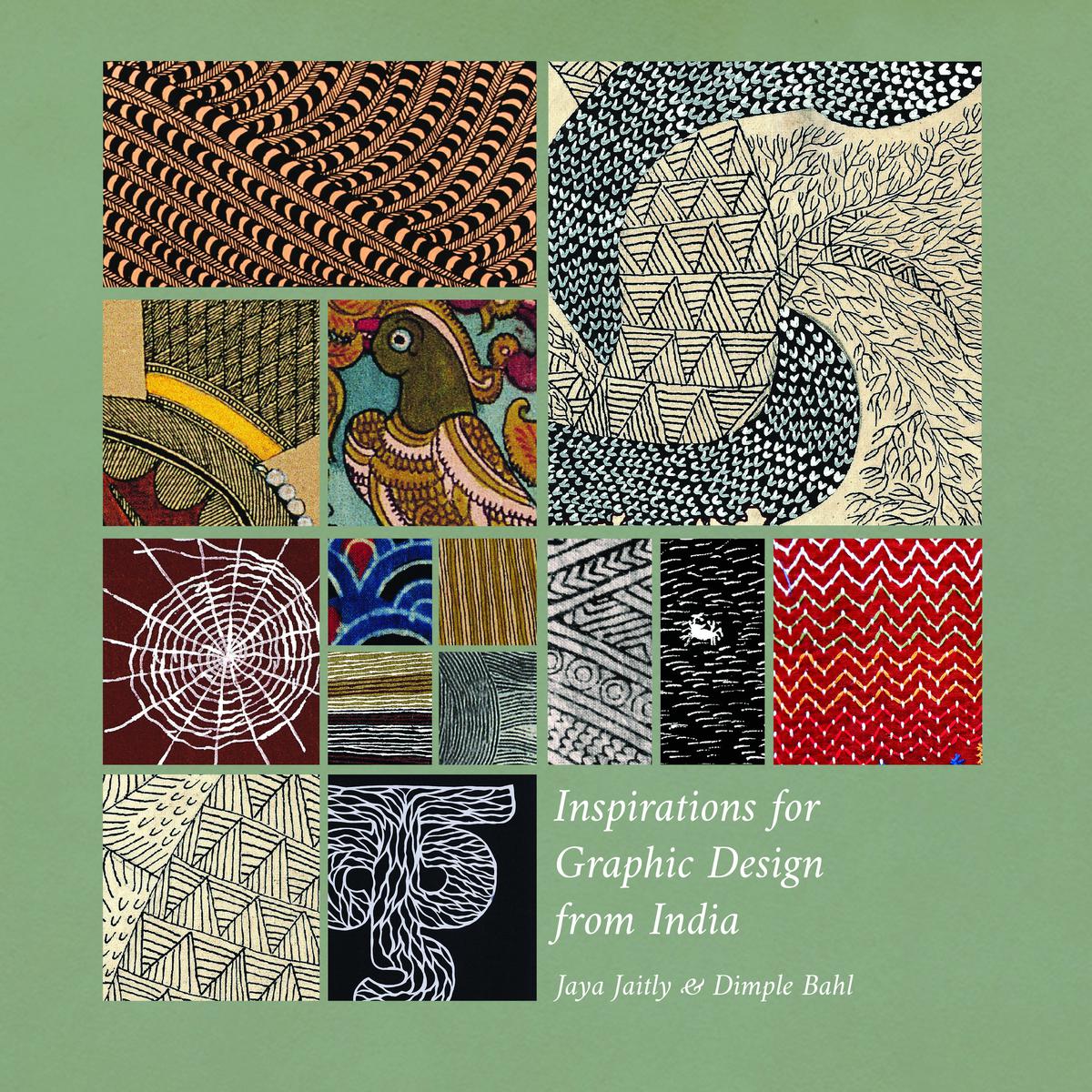

Jaya Jaitly’s latest book is a departure from what came before — from textile, craft and all things handmade. Instead, it’s a deep dive into design thinking. Inspirations for Graphic Design from India, co-authored with professor Dimple Bahl of the National Institute of Fashion Technology (NIFT) and published by Arthshila Trust, advocates an overhaul of design education in India by recognising indigenous sources. “I researched all the [available] forms of teaching the principles of graphic design that I could find. They were soulless and limiting, only geared towards a commercial approach for the printing industry,” explains Jaitly. “I felt we had a field wide open to add our bit.”

Jaya Jaitly

The years of researching — online during the pandemic and then at libraries and through discussions with scholars — have led to a book that compels us to reevaluate our sources. Edited excerpts from a conversation with the writer, crafts revivalist and activist.

Why have we failed to effectively decolonise graphic design education in India even today?

We lost our confidence in many creative areas as a direct result of the dominant industrialised approach during colonisation. It took us time to hold our heads up and independently explore India through a lens that was more culturally tuned to the daily lives of our non-westernised classes. Just as Japan was initially very imitative in its industrial rebuilding after WWII, we have an elite section that is still imitative of the West in language, dress and lifestyles. The freedom movement gave us political freedom, but freeing our minds is taking longer.

Inspirations for Graphic Design from India

You use the term ‘Indian design’ in the book. Could you tell us a little more about what constitutes that?

Indian art and Indian food are catch-all terms that mean nothing much. These are as varied and widespread as the biodiversity, topography, dialects, food habits and identity motifs of different communities and regions across India. Symbols and colours, festivals and rituals change according to local conditions and histories — and design motifs emerge out of these. What a wealth of inspirational material we actually have lying unnoticed!

For example, to help draw craftspeople out of the disconnect between literacy and craft skills, I introduced them to calligraphy through a project called Akshara – Crafting Indian Scripts in 2011. Every alphabet, word, phrase, poem, or song in their regional language could be embellished into a new design. They surpassed all my expectations by creating 150 museum quality exhibits, covering 21 craft forms and 16 Indian languages across 14 states. The resulting exhibition showed a new design inspiration that cut across disciplines.

Akshara – Crafting Indian Scripts

Akshara – Crafting Indian Scripts

[Poet-playwright-philosopher Rabindranath] Tagore’s sketches scattered across many of his handwritten poems are also fine examples of indigenous graphic design. My point is, look within the Indian cultural world to find a cornucopia of inspiration.

I feel that your book is an attempt to institutionalise the work of rural craftspeople, whose skill, labour, and genius is often unrecognised. Would you agree?

Absolutely. This is, in a way, embedded in all the work I have done for over four decades. Craftspeople need opportunities to flourish, encouragement from both local communities and global markets, multiple kinds of promotional platforms, and different types of design infusion. Architects and interior designers can play a role by using Indian forms and inspiration, and taking it to a different level — so that ‘craft’ is not just a product on a shelf or online platform waiting to be sold.

Laheriya dyeing

Are there Indian designers and artists who you feel are best using indigenous inspiration and design in their work?

I would rather point to a few trends established by some individuals and brands. The wider approach by older names such as [Ahmedabad-based graphic designer] Subrata Bhowmick; fashion designers like Ritu Kumar; the fashion sensibility brought out by Good Earth’s design team; the unknown typographers who work on English fonts based on Indian scripts. Tara Books combines Indian art with graphics and design layouts in their books for children, but that art lovers of all ages can also acquire. Subtlety and sophistication in any design form is longer lasting. Indian design is always meaningful in its original form. We should respect that rather than chase after market trends.

Wooden printing blocks

The house of a Lambani craftsperson

Who is your target audience?

The book is for students of all design institutes, corporates — for logo and brand creation — advertising agencies and digital media designers. And if I can flog my present ‘pet peeve’ horse, it’s also aimed at those persons in bureaucracy who deal with public spaces, and have lowered the public aesthetic to the level of kindergarten wall art. City walls and facades that are painted to cover up squalor, or to try and impress foreign delegates, are ghastly ideas of design that consist of imagery of bumblebees and butterflies, balloons and daisies. The ‘Indian’ alternative is always the different asanas of the Surya Namaskar. If only each state delved a little deeper into Indian sources and asked a traditional artist to design a mural.

An arts writer, the interviewer teaches literary and cultural studies at FLAME University, Pune.

[ad_2]

Source link