[ad_1]

We are at the Kolkata Centre for Creativity where I am trying to sneak a picture of a block print of cultural icon Begum Akhtar on a blouse. Its wearer, Mamta Varma, runs Bhairavi’s Chikan in Lucknow, with 300 women who do fine chikankari embroidery. Noting my interest she reveals that the unusual blouse was made by Meeta Mastani, co-founder of Delhi-based printmakers Bindaas Unlimited, to commemorate the singer’s 100th birthday.

A few feet away, the inimitable Darshan Mekani Shah, founder of Kolkata-based not-for-profit Weavers Studio Resource Centre, points to a gold-and-black cotton sari covered in hand-woven motifs of earrings. “This is a dul [earring in Bengali] jamdani,” she says. “There are only two of them that we know of. One belonged to the late Ruby Ghaznavi [activist and a pioneer in the revival of traditional Bangladeshi jamdani], and here is the other.”

Darshan Mekani Shah

Large ornate paisleys sit resplendent on either corner of the pallu. As a group of collectors, historians, curators and journalists peer closely at the sari, Shah continues, “It is of a very high thread count, takes ages to weave, and requires exceptional skill. We have tried to commission another one, but the unavailability of fine yarn and zari, or just the sheer artistry and skill that is slowly disappearing, is making it difficult.”

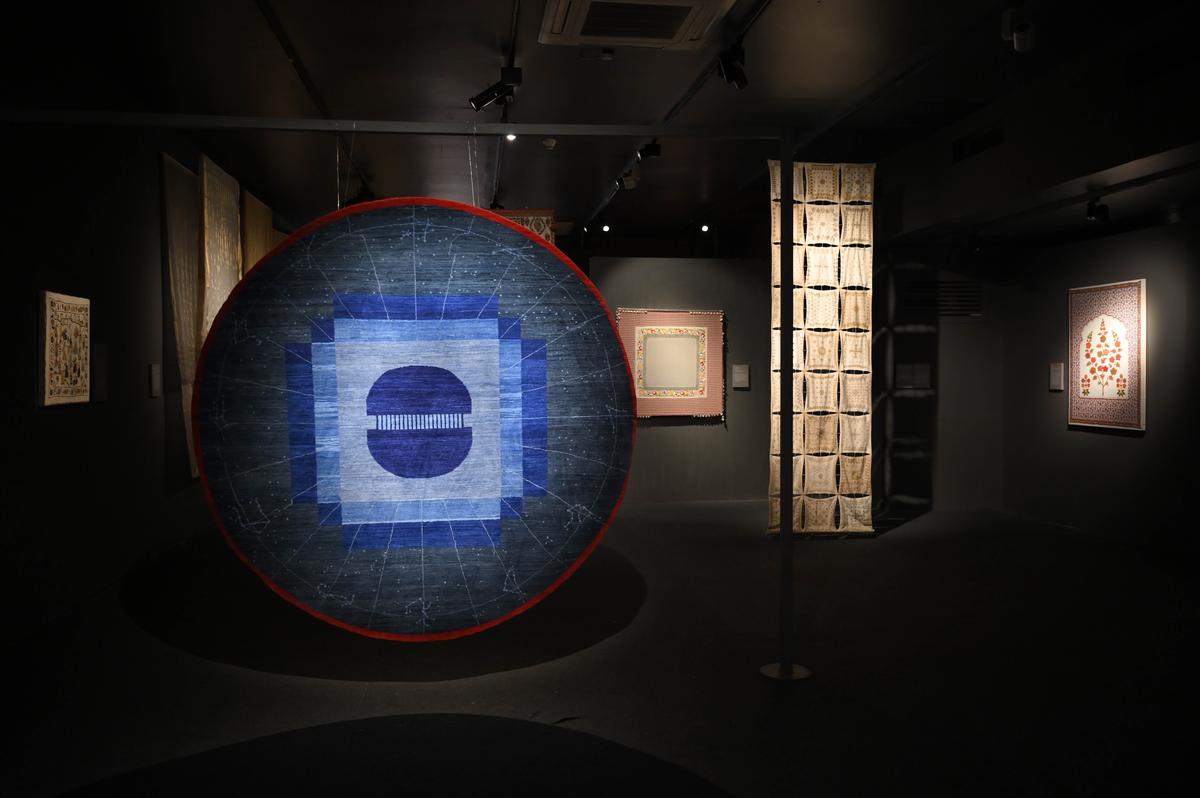

Shah is the project director of Textiles of Bengal: A Shared Legacy exhibition. The textile revivalist’s journey began over 34 years ago when she met Japanese collector Hiroko Iwatate, and started honing her sensibilities towards high standards of materials, craft and design. In 2020, she set in motion plans for a multi-year in-depth study of Bengal’s little-documented textile history, and this exhibition is its first public expression.

The opening weekend symposium saw experts such as British scholar Rosemary Crill, Italian ethnologist Paola Manfredi and author Pika Ghosh lead talks and walks. “The idea was to gather museum curators, collectors, and textile and art historians on a shared platform to address the many questions about the provenance, history, geo-politics and policies related to the textiles of undivided Bengal and fill in the gaps,” she says.

“These gatherings are as much about celebrating ancient textile traditions as they are about learning from history and taking the conversations forward. Backward and forward integration, respect and recognition, and being true to the narrative and sharing that, is imperative.”Darshan Mekani ShahFounder, Weavers Studio Resource Centre

Curator Mayank Mansingh Kaul, meanwhile, walks 12 of us through the survey exhibition with around 120 artefacts from the 17th century to the present — representative of the different traditions of weaving, embroideries, printing, and tie-and-dye. He points out patron textiles that were commissioned for royalty, such as a gossamer fine angrakha with the Awadh coat of arms, prayer caps covered in fine chikankari, Haji rumal, an embroidered cloth that weaves together religious rituals and artistic resilience, and intricate kantha work.

Mayank Mansingh Kaul

We stop at a length of Dhaka muslin with woven motifs that many collectors of Bengali handloom saris would be familiar with. The sampler is a contemporary recreation of motifs such as fulwar (flowers arranged in straight rows), kalaka (paisley), tesra (diagonal patterns), and panna hajar (thousand emeralds) that date back hundreds of years. A couple of women in the group are wearing Dhakais and, to our collective delight, the same patterns grace their saris. “This is exactly why such survey exhibitions are important,” says Kaul. “Textile practitioners are inspired to reproduce what they see, and a lot of the historical textiles are not accessible to everyone. Most of them are locked up in museum archives or with private collectors.”

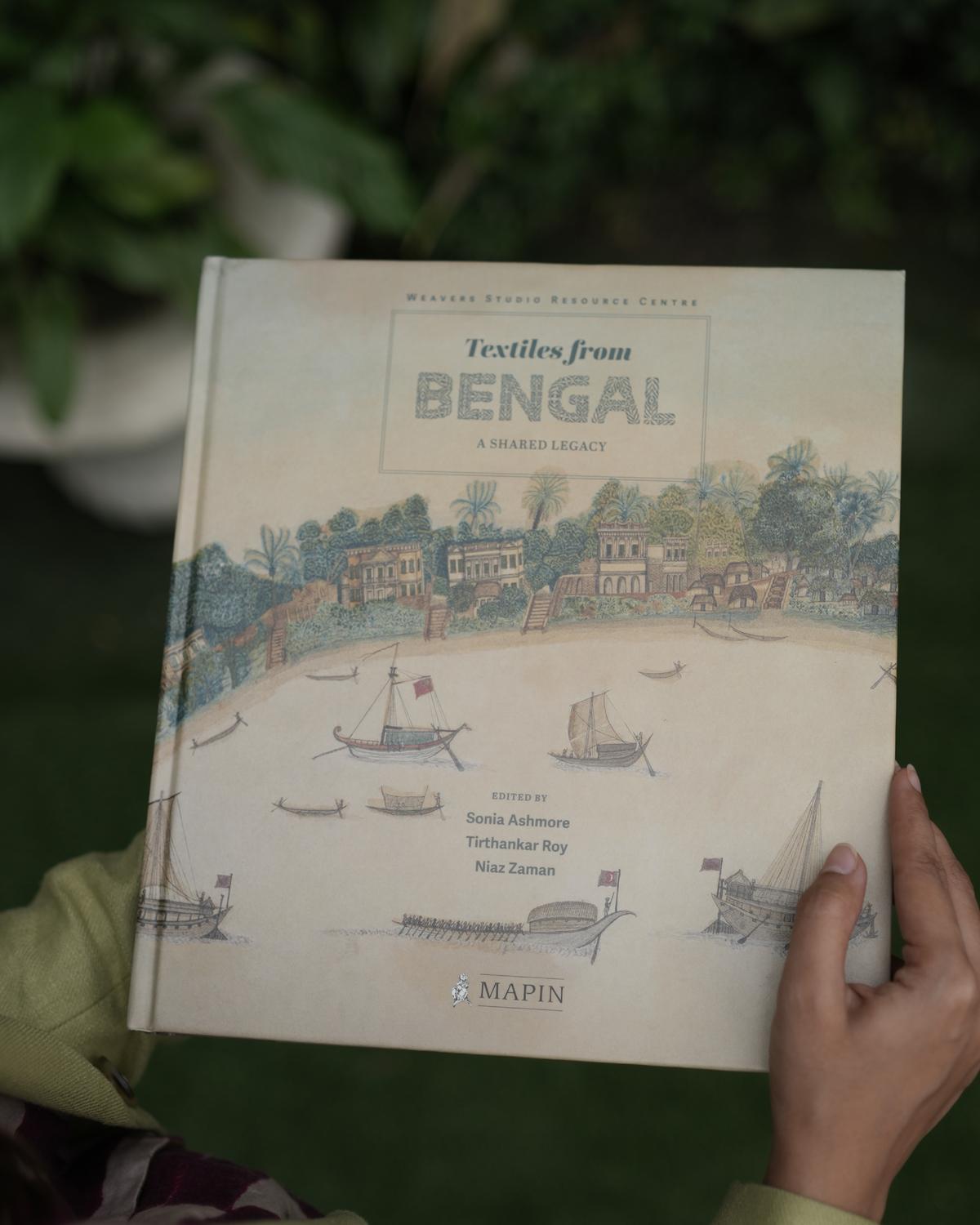

Book launch

Textiles from Bengal: A Shared Legacy (Mapin Publishing; ₹4,950) is also a weighty book, carrying within it the evolving story of textiles from undivided Bengal, told through essays from scholars, anthropologists, historians, and textile practitioners. Launched at the symposium, it is edited by design historian Sonia Ashmore, economic historian Tirthankar Roy, and author Niaz Zaman. The essays range from trade and consumption to design and production, along with insightful pieces on the world of Bengali textile practitioners from the 16th to the 20th century.

Stunning photographs of never-before-seen fabrics from museums and private collections — of diaphanous muslins, sturdy quilts, a 19th century velvet coat embroidered with Basra pearls, embroidered caps and bedspreads — accompany the essays. Illustrations and old maps highlighting the textile hubs in Bengal, trace the influences and impact of the tumultuous times, from the advent of the Mughal empire, to the rise of the East India Company.

Conversations are going mainstream

2025 has only just begun, and the Kolkata exhibition is one of several textile-related events happening across India. The last couple of months have seen Sense & Sensibility, a textile gallery at the annual Raw Collaborative in Ahmedabad that narrated design history in textiles; the ongoing Surface in Jodhpur, which highlights embroidery and surface embellishments; TAPI’s When Indian Flowers Bloomed in Distant Lands that tracked trade textiles across 700 years; Pehchaan: Enduring Themes in Indian Textiles at New Delhi’s National Museum, among others. March will see textile collector and revivalist Lavina Baldota’s Pampa: Textiles of Karnataka, under the Sutr Santati’s banner, scheduled in historical Hampi, with many others waiting to unfold in the next few months.

Sense & Sensibility at Raw Collaborative

Textiles have entered their popular era. Even as the industry, India’s second largest employment generating sector, is getting government support (see box inside), heritage weaves are becoming central to fashion brands and the common man. No longer are words like thread count and weaving clusters recognisable only to collectors and retailers; they are part of everyday vocabulary. A lot of this is thanks to exhibitions and initiatives by textile patrons and lovers.

“Exhibitions help create awareness, but the real impact depends on what comes next. While artisans themselves may not always be at these events, the exposure can still lead to meaningful change — whether it’s inspiring designers to work more closely with craft clusters, or encouraging consumers to make more informed choices. These conversations help keep textiles and craftsmanship in the spotlight, which over time can lead to tangible opportunities.”Gaurav GuptaFashion designer

Until recently, any serious conversation about Indian textiles would reference the Vishwakarma series of exhibitions of the 1980s, curated by Martand Singh — because it was just so distinct. Today, however, curators such as Kaul, Baldota, and Lekha Poddar (founder of Devi Art Foundation) are rewriting that script. “This engagement with the weavers and the walkabouts eventually translate into something more mindful for traditional textiles,” says Rasika Wakalkar, one of the delegates at the symposium, and the founder of TVAM, a not-for-profit that works with the rich textile traditions of the Deccan. “There is a direct and indirect influence on the ecosystems being revived and recharged, through such discourses.”

For instance, in 2023, TVAM and Maharashtra’s Directorate of Archaeology and Museums, had organised Kath Padar – Paithani and Beyond, at Paithan. The ancient town — once a bustling hub of trade, and renowned for the paithani sari, with its jewel tones in fine silks — had buzzed with the footfalls of hundreds of visitors, many of whom were weavers seeing historical textiles from state museums and private collections for the first time.

Kath Padar

“Fashion in India is still evolving, but every region has its own textile. We have so much room for every state to have exhibitions that speak to their histories, around their identity and textile traditions. If done right, India could have the best textile museums in the world. Symposiums help the textile industry and play a very big role in the textile economy and the scale of production.”Sanjay GargDesigner and founder, Raw Mango

Exhibitions inspire innovation

Generating new audiences is one of the main objectives of these initiatives, states Kaul, who has curated 20 major textile-related exhibitions in the past decade, including Kath Padar. “In India, almost everybody has a visceral connection to textiles. For every Delhi, Mumbai or Kolkata, there are now exhibitions in tier-two cities such as Coimbatore in Tamil Nadu, to even smaller towns such as Chirala in Andhra Pradesh, Anegundi in Karnataka, and Paithan in Maharashtra.”

He is also seeing an exponential rise in engagement at these various events. “Exhibitions inspire innovation, which is not possible without looking at history. There is no other country in the world that has this kind of diversity in textiles, historical material and contemporary practice. And these initiatives are opportunities to build standards of excellence and awareness.”

Ahalya Matthan, a textile patron and founder of The Registry of Sarees, a research and study centre based in Bengaluru specialising in handspun and hand woven textiles, is of the same accord. Back in 2015, her initiative #100sareespact had kickstarted interest on social media. People used the hashtag to share photos of themselves wearing saris on Instagram and Twitter, and to talk about their love of the weaves. Later, in 2018 and 2022, her exhibitions, including Meanings, Metaphors in Bengaluru, Coimbatore and Chirala, and Red Lilies, Water Birds at Anegundi, both curated by Kaul, were revelatory.

Ahalya Matthan (far left) with her team

“In Chirala [2018], the venue was an 8×20 ft classroom in a government boys school, with walls covered in fungus. We painted them white, put beige chatais on the floor, and showed three textiles each day over nine days,” she recalls. “I will never forget what Surya Babu, a weaver from Srikakulam, wrote in the visitors’ book. ‘Until I came here, I felt like a labourer. Now I feel like an artist,’ he wrote in Telugu. The simple act of displaying plain hand spun, hand woven lengths of textile somehow gave the weaver dignity. The impact of such exhibitions, especially in smaller centres, is immeasurable.”

Matthan remembers a weaver from Benaras who studied a Venkatagiri sari at length at ‘Red Lilies…’. He spoke about how he wouldn’t be able to reproduce the weave in Benares, as the Venkatagiri vocabulary is different. “But he found a zari we were looking for and helped us set up a loom at Venkatagiri, where he and a local weaver were able to reproduce that sari. I call this exchange of pehchaan and expertise,” she adds.

Red Lilies, Water Birds

| Photo Credit:

Pallon Daruwala

Artisan in the picture

While the cost of organising textile exhibitions can be quite high, as curator and textile revivalist Baldota puts it, “It is nothing compared to the price we will pay if nothing is done. No amount of money will bring back the craftsmanship and skill that will disappear in the next five years if we ignore it.”

Lavina Baldota

| Photo Credit:

Frozen Pixel Studios

Baldota’s Sutr Santati is an attempt to expand the scope of textile exhibitions from being limited to patrons and the elite to become, instead, a repository of knowledge for everyone. The revivalist, whose family trust, Abheraj Baldota Foundation, works with weaving clusters near Hampi, has taken the exhibitions to Delhi, Mumbai and Melbourne, Australia. And now, with Pampa, she is bringing industry tastemakers closer to the source, all the way to Hampi. “Textile has become a favourite medium for art, even internationally. With Pampa, Textiles of Karnataka, I wanted to bring attention to Karnataka’s rich handloom tradition. Exhibitions such as these are not only about looking back at history, it is also about looking forward and creating new work,” she says.

Sutr Santati

“The peak of this interest in textiles — not just in the design industry but also in scholarship — is what we are experiencing now, blurring the lines between craft and art”Yash SanhotraCurator and researcher, MAP

On the flip side, however, handloom revivalist Uzramma states that most symposiums on textiles are directed at outsiders. “In my experience, there is a greater need for organising symposiums and conferences amongst handloom artisans, many of whom have been carrying out extensive research and experiments in cotton farming, decentralised modes of spinning, natural dyes and dyeing processes, and textile designing.” In this regard, her Malkha project — which aims to link farmers, spinners, and weavers to each other so that they become a community of producers — has been “unweaving its role as an NGO, to weave instead a Handloom Knowledge Commons where artisan scholars are invited to share their knowledge”.

Government support required

“2025 has begun with many dialogues, and it is an ongoing process. Plenty more needs to be done. If textile practitioners, corporate bodies, and retailers pooled their resources and implemented sustainable policies for the craft communities, there would be more bang for the buck,” believes Shah. More so, if the government got involved. Baldota of Sutra Santati agrees. Her upcoming ‘Pampa…’ symposium is in collaboration with the Karnataka government. “The reason is three-pronged: it provides accessibility to the local people [buses will bring people from the clusters to the exhibition venue]; it opens up huge prospects for cultural tourism; and most importantly, as a result, the artisans will benefit.”

400 million contributors

Back in Kolkata, Varma and I are discussing the 300 women embroiderers at Bhairavi’s Chikan. A sizeable number for sure, but as professor Ashoke Chatterjee, former director of the National Institute of Design in Ahmedabad, informs me, it is just a tiny fraction of the artisans in India. “Though there is no official data on how many artisans there are, I would peg it at nearly 400 million. No other industry can match the contribution that artisans and crafts can and do make to the Sustainable Development Goals [the 2030 agenda adopted by all United Nations members in 2015 as a shared blueprint for prosperity],” he shares.

Textiles from Bengal: A Shared Legacy

Chatterjee has worked with the Indian government on the economics of the country’s craft sector, and was the honorary president of the Crafts Council of India (CCI) for over 20 years. He calls the general apathy shown towards craftspeople a crisis of ignorance. Nevertheless, he holds out hope. “Scholarly symposiums are vital. The conversations there will give rise to a sensitive understanding of the sector and highlight issues of social, political, spiritual and environmental justice, and equity,” he believes.

“Exhibitions have great reach. And social media has improved the livelihoods of many artisans. Global and local communities are directly connecting through social media with the creators, eliminating the need of middlemen.”Pankaja SethiTextile researcher

Textiles are closely interwoven into our culture. From patrons willing to spend lakhs of rupees to commission a heritage sari to middle class families who hold dear that one extravagant wedding ensemble that’s been handed down through the generations, textiles will always be relevant in India.

It’s also why Darshan Shah is not fazed by the doom and gloom narratives of disappearing craftsmanship. “The many events around textiles planned for the months and years ahead will inspire change. Because the art and craft sector in India is resilient. It has survived for thousands of years and will live on long after you and I are gone.”

At Bharat Tex 2025

Last week, at Bharat Tex 2025, the mega textile event in New Delhi, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced plans to increase textile exports to ₹9 lakh crore by 2030. The fair, which saw 1,20,000 trade visitors from over 120 countries, also showcased several Union Government schemes and policies for the sector, including the Prime Minister Mega Integrated Textile Region and Apparel (PM Mitra) Parks Scheme and the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) Scheme. With an outlay of ₹4,445 crore, seven PM Mitra parks will be set up at textiles hubs in Tamil Nadu, Telangana, Gujarat, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Maharashtra. Once completed, these will reportedly attract an investment of ₹10,000 crore and generate three lakh direct/indirect employment.

— Jigeesh A.M.

With inputs from Team Magazine.

The Textiles of Bengal exhibition is on till March 31 at the Kolkata Centre for Creativity.

The writer is a freelance journalist based in Coimbatore.

Published – February 21, 2025 02:54 pm IST

[ad_2]

Source link