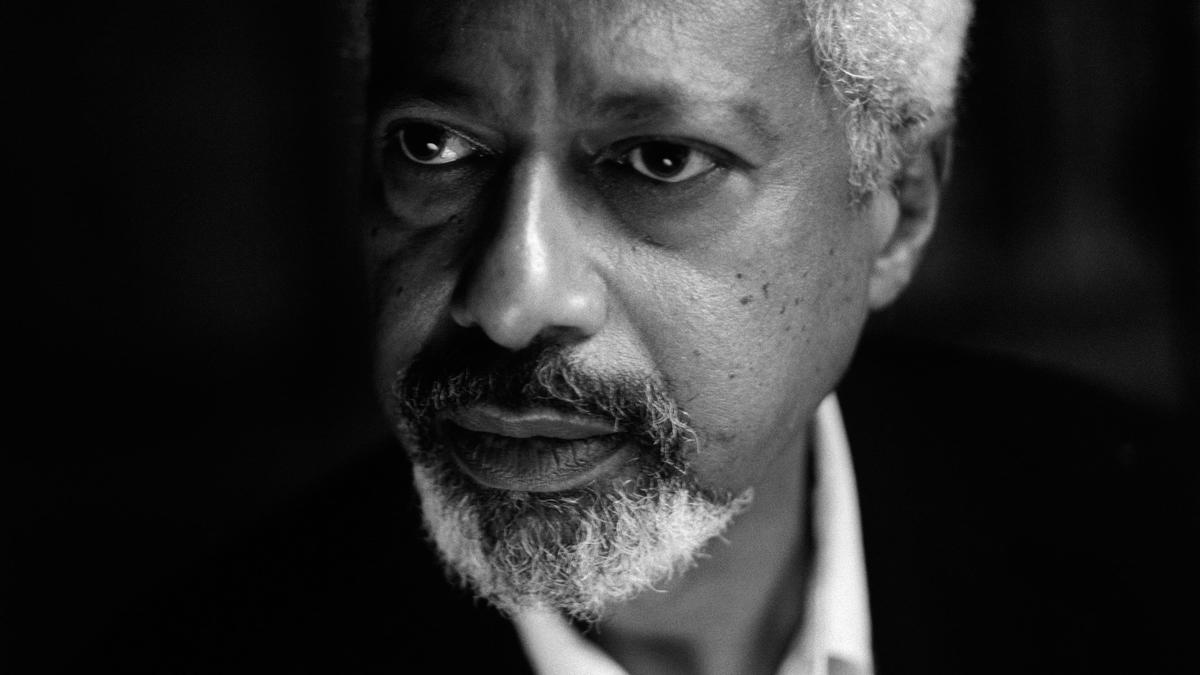

In October 2021, when writer Abdulrazak Gurnah won the Nobel Prize for his work, which the Swedish Academy described as “uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism”, he was in the middle of “writing something”. “Since this award, most of the time, I have either been talking to journalists or meeting people, so there hasn’t been much writing. The award has a global impact and everyone wants to speak to you, publishers like you to promote new editions that are coming out in new languages. After all this, I will go back to doing what I have been doing for the last 40 years,” he says.

About a week ago, at the Dhaka Lit Festival, Gurnah engaged in a conversation about his childhood, education and writings with Alexandra Pringle, who has edited many of his books. Alexandra will accompany him for a session on a life in writing, titled ‘The Essential Abdulrazak Gurnah’, on Friday, at the upcoming Jaipur Literature Festival. He will joined by Namita Gokhale, William Dalrymple and Sanjoy Roy for the keynote address on Thursday. “I’ve heard a lot about the Jaipur Literature Festival, the Pink City; so, I’m curious to see,” he shares.

Gurnah fled Zanzibar as a teenager following the revolution of 1964. He moved to the United Kingdom as a refugee and now lives in Canterbury as a British citizen. His strikingly formidable works include Memory of Departure, Pilgrims Way, Dottie, Paradise, By the Sea, Desertion, and the most recent, Afterlives, which examines the German colonial force in East Africa and the lives of Tanganyikans — as they work, grieve and love — in the darkening shadow of war. “All these books have explored many dimensions of what I think is one of the phenomena of our times — displaced people who find themselves, not necessarily always comfortably, living at places other than their ancestral homes. And I’m always interested in how people cope with events that are either tense or traumatic, and how it is that they can retrieve something from these conditions, from these moments,” he says.

For Gurnah, his experiences are the hinterland of the kind of writing he indulges in. “Past experiences always figure in my writings, as somebody who doesn’t write a genre form,” he says. Gurnah mentions that there is a growing number of interesting writers, particularly from India, Africa and the Carribean. “Those are the areas I know most about. I think it’s a pretty good time for writers, in terms of finding publishers, audiences, being heard, telling each other and world about our circumstances,” he adds.

But when it comes to reading, Gurnah says he does not have strict lines. “I don’t read crime novels. I don’t usually read memoirs. I don’t read books that want to take me to a different world, as you were in. But I don’t think otherwise I have too many restrictions. I just find that some books perhaps because the language is not too engaging or is too clichéd, then I give up, but I don’t draw lines as such,” he says. “There are millions of books, of course, produced almost every week. Now I don’t even have to stir very much because so many people send me books. I’m being invited to participate in reading in a way that is interesting and a little bit demanding because (there is) a lot of reading to do.”

To put it simply, for Gurnah, writing is a long process. His last book was published in 2020, one year before he won the Nobel Prize in Literature. But how long does it take to write a book?

Gurnah picks up a story from an idea, which could hang around for months or several years even. In the meantime, he is doing other things. “These ideas are in a queue somewhere. It takes months, sometimes years, to realise an idea. And perhaps by the time I finish, it is already changing to something else,” he signs off.