[ad_1]

The recently held Patiala Heritage Festival reminded one that the region (geographically not as we know it today) has been the cradle of culture in North India. Bharatha’s Natya Shastra was put together in this region, and around 1,000 years later Sharngadev, born in Kashmir (which was considered a part of Punjab), wrote Sangeet Ratnakar, a significant music treatise.

Classical music has been an intrinsic part of people’s lives in this region — starting from Guru Nanak, (1469-1539), the first Sikh guru, all spiritual instructions were conveyed in the form of verse, in raag.

Tracing the roots

This deep connect has kept the music tradition of Punjab alive. In the late 19th century, the ‘khayal gayaki’ of the region was linked with Patiala state. Brothers ‘Aliya Fatu’, who were musicians in the court of Maharaja Rajinder Singh gave shape to the Patiala gayaki. Aliya’s grandsons, Ustad Amanat Ali Khan and Fateh Ali Khan were popular singers of their time, who migrated to Pakistan after Partition. The gharana’s most iconic exponent Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, who was from Kasur (Pakistan) inherited that gayaki apart from being trained in the Patiala tradition. Hence the gharana is known as the Patiala-Kasur gharana.

Another popular style practised in the region was of the Talwandi gharana. Earlier, dhrupad defined the music of Talwandi, while khayal came into vogue only around 250 years ago. Historically, the first references to this style are from the time of Akbar — two singers, Chand Khan and Suraj Khan, said to be disciples of Swami Haridas, spread the music in the region, which later came to be known as the Talwandi style.

The royal patronage

Pt. Susheel Kumar Jain, who belongs to the Punjab gharana of tabla, says the brothers lived in Kapurthala, where the royal court patronised music in a big way. So much that musicians in the court of Raja Nihal Singh were discouraged from singing raag Hameer since the raja didn’t find the plaintive quality of Hameer appealing. His son Kanwar Bikrama Singh rescued the senia court musician Mir Nasir Ahmed from the Delhi court during the 1857 Mutiny and took him to Kapurthala. Thus came into the existence the Kapurthala gharana.

Later, when Kanwar Bikrama settled in Jalandhar, he started the Harivallabh Mela (now Sangeet Samaroh), incidentally the oldest classical music festival in the country.

According to Susheel Kumar Jain, the entire Punjab region was once known for its classical music tradition. Another oldest and popular music mela that used to be held in Hoshiarpur till the 1960s was the Baddho-Ki Gosain, which featured many music greats. The Sham Chaurasi gharana is also said to be an offshoot of the Talwandi style, extant for 11 generations.

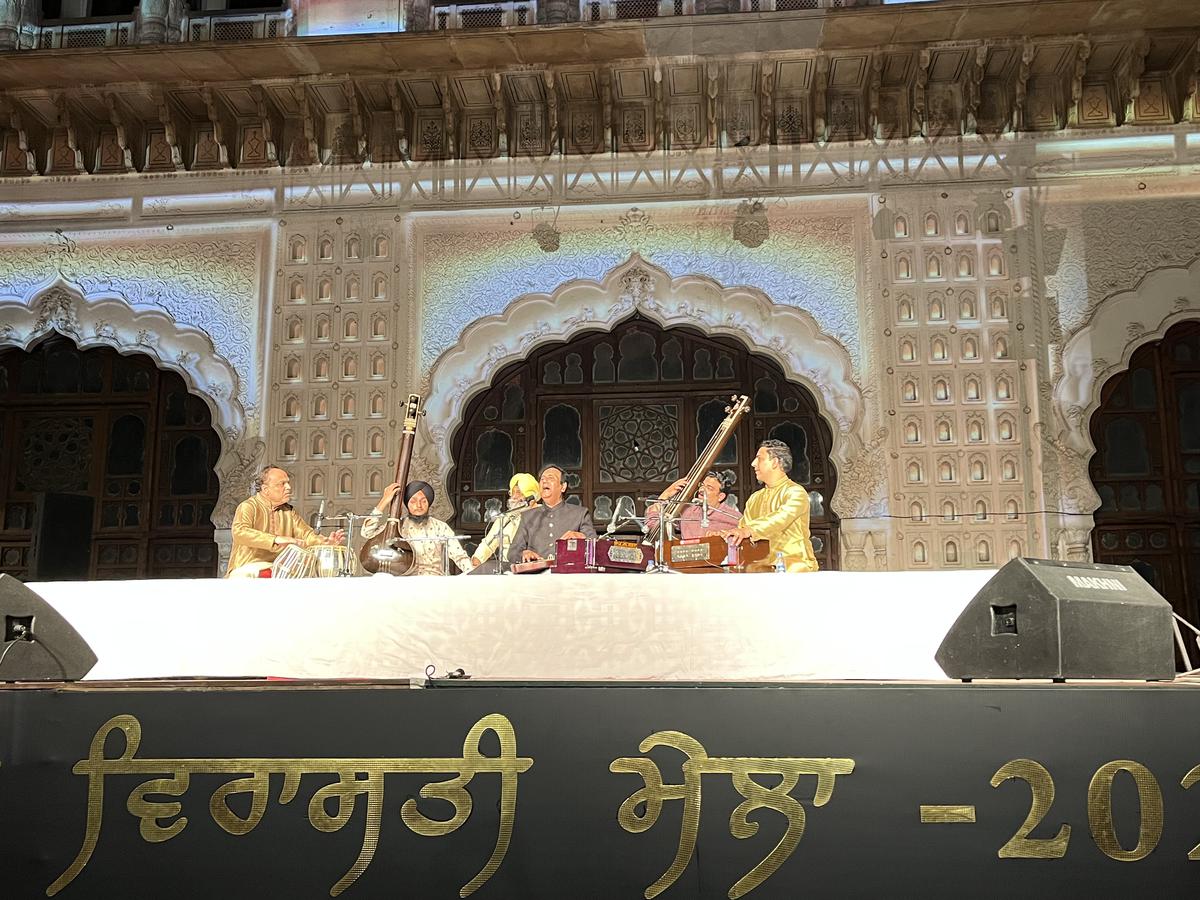

Today, the Patiala gharana and the Sikh Gurbani are known for their distinct vocal style, and the Punjab gharana for its tabla playing technique. To celebrate this tradition, the Patiala Heritage Festival is organised in February every year and features eminent artistes. This year’s edition had a formdible line-up, including Ustad Wasifuddin Dagar, Pt. Sajan Mishra, and Nivedita Singh (from Patiala).

Shujaat Khan performing at the festival

| Photo Credit:

Patiala Heritage Festival

Myriad styles and forms

Ustad Shujaat Khan impressed with his rendition of Tilak Kamod followed by a lilting folk song ‘mitti da bawa’ in Punjabi.

Sarod artiste Pt. Biswajeet Roy Chaudhury, a well-known disciple of Ustad Amjad Ali Khan and Pt. Mallikarjun Mansur, lent his own creativity to raag Maru Bihag, and presented it in dhrupad ang. This was followed by four compositions in Kafi.

Manjari Chaturvedi

| Photo Credit:

Patiala Heritage Festival

Manjari Chaturvedi, whose performance was titled ‘O Jugni’ also featured qawwals from Amritsar, headed by Ustad Raajhan Ali. Balkar Sidhu’s story telling heightened the production’s appeal. The lighting and costume stood out too. This was the first time ‘O Jugni’ was presented in Punjabi.

The most interesting presentation was the vocal recital by Jawaad Ali Khan, grandson of Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan. Reminiscing about his family’s home near Sherwali Gate, Jawaad took the audience back in time to an era of shorter pieces in so-called ‘simple’ raags favoured by his grandfather. Jawaad focused on the emotive content of the compositions rather than the ‘tanaiti’ (taans) for which the Patiala gharana is known. He started with raag Kamod, instantly reminding of the Ustad , and followed it with raag Hameer. The audience response led him to present raag desh though he wanted to sing thumris, identified with his gharana. His sang a khayal in Punjabi, ‘Aaya ve saawan aaya, khushiyon leyaaya’ (the rains have come, bringing with them happiness). He also sang a snatch of a rare khayal in raag Sorath, which is very close to Desh, and reverted to Desh with an old composition, ‘Piya kara tharakat dekho dharakat hai mori chateeya’.

Jawwad Ali Khan

| Photo Credit:

Patiala Heritage Festival

On request, Jawaad sang his grand uncle Ustad Barkat Ali Khan’s popular thumri in Pahari ‘Baagon mein’ where his traditional delineation of the raag was a delight. His repertoire also included ‘Lajo lajo’, a popular dhun in Dogri, of the Jammu region, which he said was a favourite of his family, and ‘Yaad piya ki aayi’, which he clarified was Punjabi ‘maand’ and not raag Bhinna Shadaj.

The last unsung ‘khalifa’ of the Patiala ‘gharana’ Ustad Baqat Hussain Khan (cousin of Ustad Amanat Ali) gave a new Sufi slant to the Patiala gayaki. His disciple Ustad Puran Shah Koti trained popular Punjabi singer Hansraj Hans in this style, who in turn, taught his guru’s son Master Saleem, whose performance brought the festival to a close.

[ad_2]

Source link