[ad_1]

First, there was a quad-building uphill climb to reach the accommodation every evening. Then, a weak-knee-straining descent on three consecutive mornings, albeit through wet-forest smells, and past the stone and wood of buildings that blended into the greens and browns of nature. In between, as the mist wafted in and out of Doon Valley in Mussoorie, the hours were filled with camaraderie, bridge-building, and chatter around how an adult community of educators and counsellors could support a generation of students to reach their peak potential.

At what was heralded as India’s first conference of mental health for schools — organised by Woodstock School in Uttarakhand towards the end of September — there were over 200 attendees from 77 schools. David Bott, who runs The Wellbeing Distillery in Melbourne, Australia, that consults with schools and educators, was the lead speaker, talking about choosing connection over correction, using the vocabulary of emotions, and the psychological sigh (a breathing exercise that helps reduce stress).

It was only towards the end of the Pathways to Flourish 2024 conference that Binu Thomas, who heads personal counselling at the school, spoke about its Wellness Ambassador programme that brought children into a circle of trust. Through the programme, 15 student volunteers (for 480 schoolchildren) are trained to be peer supporters. They are put through training that uses role play, communication games, and scenario building among other tools, for 18-20 hours over a few weeks.

Woodstock’s Wellness Ambassadors

The aim is to channel their strengths to be active listeners to fellow students, while also being taught about confidentiality, conflict management, and more. This spreads a culture of support through the student, staff, and parent community. “I was convinced that counselling had to go beyond an in-the-room service,” says Thomas, of the programme that has been running for three years now.

Students as peer influencers

Globally, such programmes are gaining more ground in the face of twin challenges: the rising number of adolescents struggling with mental health issues and a dearth of resources to help them. In 2021, UNICEF brought out The State of the World’s Children report, On My Mind: Promoting, Protecting and Caring for Children’s Mental Health, initiated to examine the mental health of children, adolescents, and caregivers. It found that while 83% of 15- to 23-year-olds in 21 countries believed that a good way to heal was to seek support, in India, only 41% believed this. And in a country where up to 14% of children report “often feeling depressed”, the report also stated that “a cross-sectional study of 566 secondary school teachers in South India found that nearly 70% believed that depression was weakness, not sickness…” It is in this context that schools are now thinking harder about a peer support system for children.

At Woodstock, through the programme, a group of students, mostly 15- to 17-year-olds, help with various aspects of boarding school life. They are able to identify homesickness in students who have just joined, alert the counsellor if someone shows worrying signs of isolation or anxiety, and hold space for those who find it easier speaking to someone their age or a few years older. The team also helps host events around anti-bullying, cyber detox, sleep awareness, among others.

Thomas says there is a strict filtering process for enrolment, involving a 400-word essay on why a student wants to be a Wellness Ambassador, references from a ‘dormitory parent’ and teachers, and a final interview. Peer supporters work with the counsellor closely. “We choose those who are all-rounders so they can also mentor students who may be struggling with time management or study resources,” she says. Part of the process is to make sure the ambassadors are visible so children can approach them, but also for them to seek out children who may feel lonely, for instance. “So an ambassador may go and just have lunch with that child for a few days or meet them on the games field.”

Peer mentors are able to identify homesickness in students who have just joined, alert the counsellor if someone shows worrying signs of isolation or anxiety.

| Photo Credit:

gawrav

On the last day of the conference, the Wellness Ambassadors gather for a chat, instinctively suggesting everyone sit in a circle, the way they do at weekly team meetings. Sahiba Sindhu, 17, remembers her time as a new student in class 9, and how an ambassador helped her feel less homesick. Twisa Kanwar, 15, talks about how they trained in listening not just to the words, but also to look out for body language. Snigdha Matanhelia, 16, notes the change in her own interactions with people: “I realised I was giving solutions. Now, I just listen and mostly people come up with their own solutions.”

Thomas remembers one time at the end of term when the team got an email from a student expressing some anguish. “An ambassador reached the child’s room and stayed there for the first five minutes before the dorm parent could reach,” she says.

Aadi Mehta, from Ahmedabad, who graduated from the school last year, used this idea of all-round campus wellness as his main poll plank when he stood for elections at the George Washington University, in Washington D.C., this year. As a Wellness Ambassador, he remembers the non-judgmental attitude that students needed to develop, to talk to peers. “It helped me form genuine connections in school,” he says. He is now one of the senators at university, and hopes to make the college’s functioning mental health support more visible to people so they reach out for help.

Children respond to care

About 45 kilometres away from Mussoorie is the Navadha School in Dehradun, run by the Building Dreams foundation. Set up just 300 metres from Sisambara basti, a colony of rag pickers and daily wagers, Ranjit Bar, 28, runs the school, where the children also have a peer support group. “We need it even more because so many of the children come from challenged backgrounds. A number of them are surrounded by substance abuse and financial abuse,” he says.

Bar says the peer-to-peer programme began with children who had a better grasp of academic concepts teaching younger children and slower-learning peers basic maths or language skills. “These are all first-generation learners, and the main aim is to keep them in school. When we meet a child, we start the actual school curriculum only after six months,” he says. Children from three to 16 are integrated into school through games and the food provided. The peer supporters step in at this point and stay with them if they need further help.

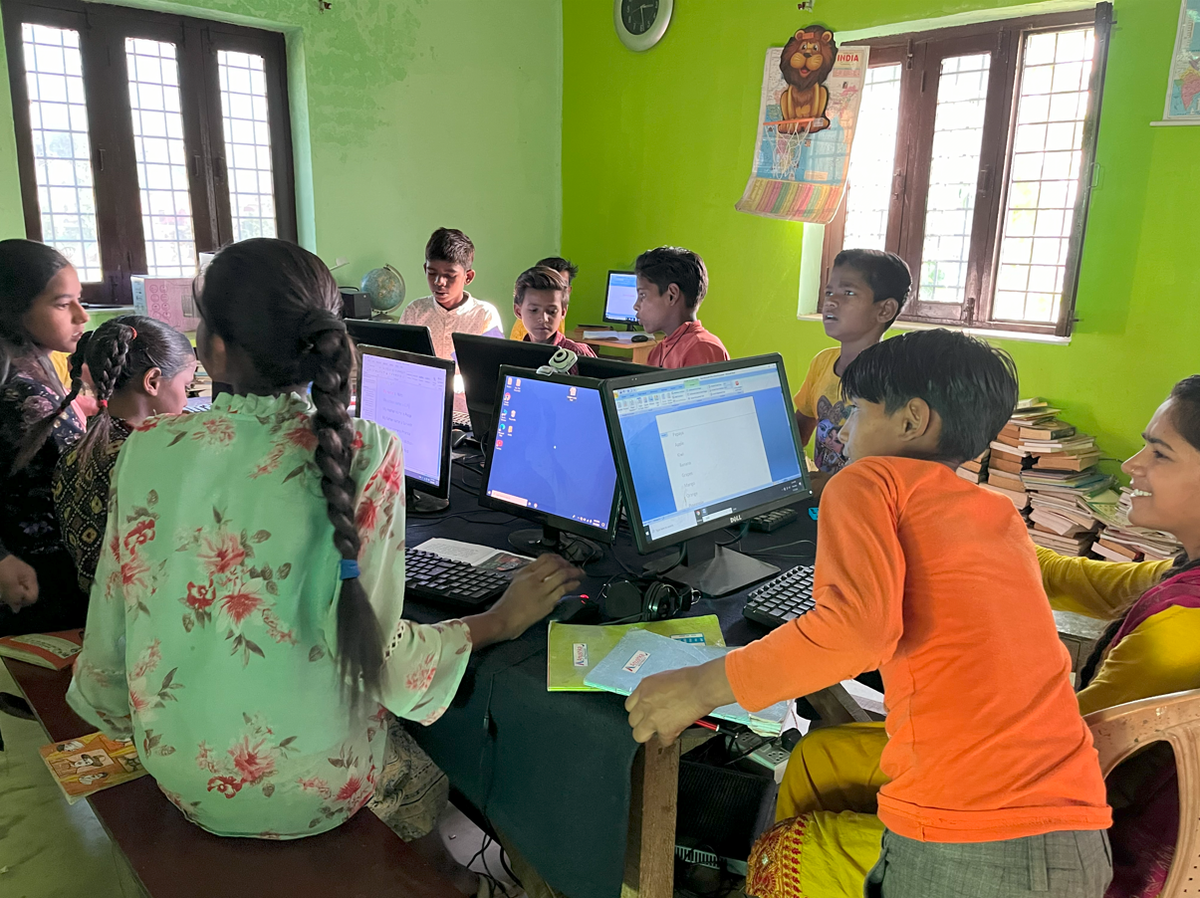

Children at Navadha School

“The world creates for people who have,” says Bar, directing all his attention to those who have little. Seventeen peer educators for 117 children help children learn about hygiene, health, and nutrition as well. Since the children come from the same area, they chat with each other easily, but they have also learnt when to escalate to the special educator the school employs.

‘Kids must be taught boundaries’

Aneesh Kumar, the associate professor of psychology at Christ University, Bengaluru, agrees that peer listeners can catch vulnerabilities early, so adults in the team — whether a teacher or counsellor — can take pre-emptive or preventative measures. “Students can be given age- and developmentally-appropriate tools to talk about mental health. For instance, if sex is being spoken about in a group, a peer educator can lead the others, with support of training from professionals and evidence-based information,” he says.

He adds, however, that the students must be hand-held at every stage and work closely with the counsellor, so they don’t feel the mental load and are well-equipped with information and skills. “There are a few downsides, like they may take on more than they can handle. To limit this burden, they must be taught boundaries,” he says. Another downside is that if the emphasis on confidentiality is not strong enough, it may turn into snitching, gossiping, and spying.

Students must be hand-held at every stage and work closely with the counsellor.

| Photo Credit:

pixelfusion3d

Peer education is part of a larger, positive youth development framework that institutions adopt. Its central idea is the harnessing of students’ strengths through an enabling environment. In layperson’s language, it’s about drawing a person’s attention to what they’re good at, so they lean in to those traits and skills. Dr. Kumar says the overall framework percolates down to every area of school life, and has proven to be successful around the world, in terms of how teachers record the changes in “classroom climate”.

This is why schools are increasingly looking at it. Anju Soni, principal of Shiv Nadar School in Noida, says while three wellbeing prefects have been a part of the student council for three years, they are in the process of having 14 buddies who will chat with students about issues that concern them.

After COVID-19, many schools felt the need for a more robust system that would build resilience, collaboration, and empathy. Peer support is a part of the social-emotional learning (SEL) ‘syllabus’ that many boards began to develop in the aftermath of the pandemic. While the Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE) rolled out the Adolescent Peer Educators Leadership Programme in 2021, the Council for Indian School Certificate Exams (CISCE) is in the process of formulating a plan that will fan out over its 3,000-odd schools countrywide, in the next academic year. Joseph Immanuel, chief executive and secretary of the CISCE board, says, “The idea is for every teacher to be a counsellor.” Then, through teacher and student training, the peer-to-peer support will be introduced.

Parents must be looped in

Most schools do not keep parents specially informed about peer counselling programmes. They treat it like another school activity, involving the children’s freedom of choice. For now, it’s mainly schools that have enough teacher and counsellor support that are implementing it. But once a peer-to-peer programme becomes mass, parents may need to be inducted into it, so day scholars can be supported at home too.

Peer Mentors at the Kodaikanal International School

Narrative therapist Shelja Sen, who co-founded Children First, an organisation that builds programmes around wellbeing and resilience, says parents must be a part of the process when a child decides to volunteer for a peer listening or mentoring programme. “It needs to be a collaborative decision involving the school, child, and parents, because sometimes a conversation can be very intense for an adolescent,” she says.

When issues such as self-harm and body image tied in with self-hatred and disordered eating come up, it can overwhelm a peer listener, even if they have been taught to escalate it to the school counsellor or a teacher. “So, the programme has to be really well thought through,” she adds. It’s not about the school sending off an email to parents informing them about it, but about the school reaching out to parents to do an in-person orientation, pointing out the possible problems and triumphs that a child may see through the programme. “Some parents may simply say ‘no’ unless the skills the peer listener will develop are pointed out to them,” says Sen.

First-time mentors

Delhi’s MCD primary school in Amar colony has students from a few neighbouring areas, where many of the parents work in the homes around, or as daily wage labourers, or auto drivers. The school has a buddy system where each child is paired with another. “It began as support for new children, but has now extended across classes 3 to 5,” says Urmila Chowdhury, co-founder and director of the non-profit Peepul that has worked in collaboration with the school since 2017. The idea is to build a community where people help each other.

Children are paired depending on their learning and skills, so someone good with numbers may be buddied up with someone who draws well. Every lesson follows the structure ‘I do’ (where the teacher explains), ‘We do’ (children collaborate), ‘You do’ (children work independently). Within the we-do time, buddies tackle exercises together. The think-pair-share method, while old, works, says Chowdhury, who spent many years as a teacher in Shri Ram School, Delhi. When asked about the buddy system, a group of class 3 students use the words “ek saath [together]” several times over.

Delhi steps up

Apurva Sapra, who heads the Delhi government’s School Mental Health Initiative, says their programme has two arms: one for teachers to understand the impact that mental health issues has on students, and the other that loops students in — through circle time and life skills education. Circle time is student driven, and if it throws up issues, school psychologists get involved. They also have mobile mental health units run by the Institute of Human Behaviour & Allied Sciences that visit government-run schools. The programme currently runs in 35 government schools, and an evaluation is expected next year before it is rolled out to the 1,000+ other schools.

Not far from the MCD school is Tagore International School. Here, Aahana Jain, 14, in class 10, is part of the Peer Mentoring club with other students from classes 10 to 12. Every week, the school has three zero periods, where students take up topics such as bullying, social media, or time management. “The teachers are not in the classroom, so students can open up about what they feel,” she says. Her mother, Aanchal Jain, a dentist, remembers her own time in a girls’ school when “so many topics were taboo we could not even talk about them to our peers for fear of being judged”.

Aahana Jain (right) with her mother Aanchal Jain

Priyanka Randhawa who is the project director says they take small triggers and use them as big lessons. “A child from the Northeast told us how targeted she felt in Delhi’s public spaces, how people would call her ‘momo’ and ‘chinky’. So we took up the idea of diversity and bullying,” she says. She adds that the avenues of bullying have increased: it’s no longer just on the playground or in the classroom, but also online. “Someone can just expel you from a WhatsApp group, and a child could feel terrible about that.” Younger children, she feels, tend to listen more to older children than their parents, and that’s where the peer mentors come in.

Meanwhile, at Kodaikanal International School, Shiv Gandhi, 15, has signed up to be a Peer Mentor. He talks of the “adolescence to adulthood” GenDerations programme that the school has signed up for. “We learnt that the person [who the peer is listening to] does 80% of the talking and we do just 20%, and we give them some [non-verbal] indication through the conversation so they know we are listening,” he says. He liked the trust-building exercises within the group: “It allowed me to share about myself, even though it was with some whom I had never spoken to.”

Shiv Gandhi

It is this understanding of vulnerability that the peer supporters take into the school, to form deeper bonds. As Gilda, a counsellor at KIS says, “They have experienced how uncomfortable it is to be honest about their own feelings and emotions, that they become open and understanding to those who reach out to them.”

sunalini.mathew@thehindu.co.in

Published – October 10, 2024 03:49 pm IST

[ad_2]

Source link