[ad_1]

Ammani Ammal was part of a devadasi troupe that went on an 18-month tour of France

Somewhere in Paris, a winding cobblestone path adorned with Hausmannian buildings leads to a small iron gate. Beyond the tree-lined path lies a home, now converted into a museum, housing within its main chamber, a glass cabinet. A bronze sculpture of Ammani Ammal, a devadasi, sits within, staring at the world around her through a glass pane. How did Ammani end up in Paris?

In the year 1838, a troupe of temple dancers and musicians associated with the Vaishnavite temple in Thiruvananthapuram were approached by French impresario E.C. Tardival for a series of concerts in France. Originally from Pondicherry, this talented troupe was offered the handsome sum of ten rupees per day, plus a five-hundred rupee advance, and an additional 500 upon the completion of their 18-month tour. After mutual agreement, much effort was put into releasing these artistes from temple service and drafting a contract to be signed at the French notary, completely in French. All the details of their stay and schedule were recorded. Of the eight-member troupe, seven signed their names in Telugu and one in Tamil — providing an interesting glimpse into the cultural cosmopolitanism of the community.

Tardival arranged for travel by boat to Bordeaux where they all arrived on July 24, 1838, to witness a ballet. Historical accounts describe their presence in the audience as a spectacle in itself, providing considerable distraction from the western classical dancers on stage. They eventually made their way to Paris, and after felicitation by King Louis Philippe, they were housed in a bungalow with guards on the banks of the River Seine. From here, they would eventually tour London, Brighton, and several other European countries.

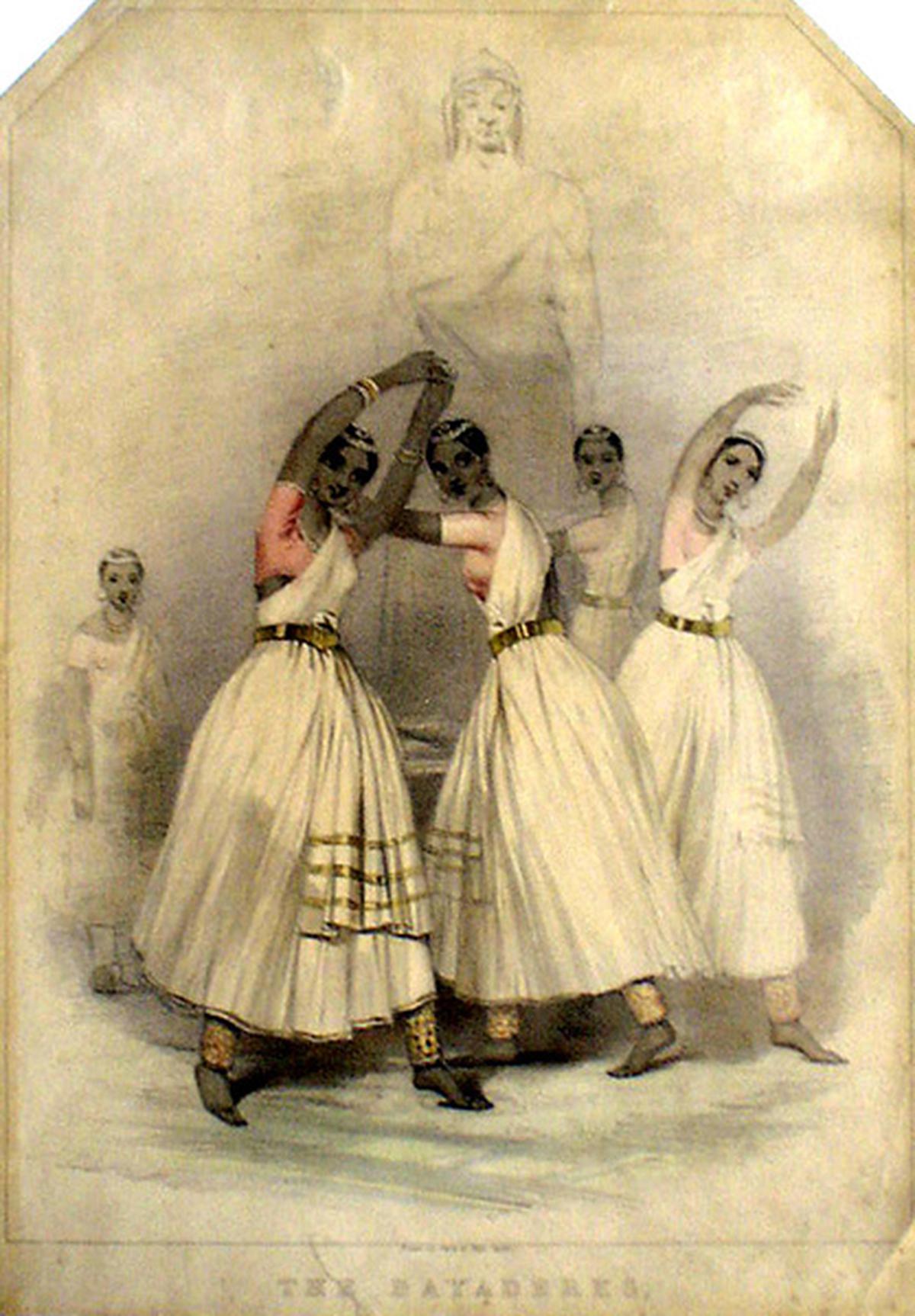

A lithograph showing the group dancing ‘Malapou’

| Photo Credit: New York Public Library

The troupe consisted of five female dancers, including a six-year old Vedam (described by the French as “Cupid painted black”) and Thillai, who was in her 30s. Thillai danced with her two daughters, Soundiram and Rangam, both aged 14, and her 18-year-old niece Ammani, the principal dancer. They were accompanied by three male musicians to perform nattuvangam, play the maddalam drum and the thoothi bagpipe-horn for pitch. Ammani, by all accounts, was tall, slender and stunning. Such was her charisma that her departure from Pondicherry incited a boy, who was besotted by her, to jump into the water and swim towards her departing ship, calling out to her.

The repertoire of these artistes may not be recognisable to the modern Bharatanatyam dancer. With names translated by foreign organisers, like ‘The Robing of Shiva’, ‘The dagger dance’ and ‘The widow’s lament’, it is difficult to discern what exactly they might have danced. Two particular pieces stand out for their similarity to modern Bharatanatyam repertoire — the first titled ‘Salute to the rajah’ was performed by Vedam. This was likely a variant of the salaam-daruvu or the shabdam, which was traditionally used to greet the king. The second piece (and possibly most written about) was the Malapou that bears some similarity to the alarippu and featured three dancers together on stage.

Impressive as they were, none stood out as prominently as Ammani. Everyone, who saw her and her dance was left awestruck, particularly Jules Theophile Gaultier, a dramatist, poet and critic. He was privy to private rehearsals at the dancers’ bungalow in Paris. His writings reflect his love for her physical and theatrical presence. “Olive-gold colour skin, silky rice paper texture to the touch, rounded hips” he observes, making note of her ornaments in detail. He went to the extent of commissioning popular sculptor Jean Auguste Barre (who had worked on the sculptures of several prominent ballerinas) to cast the image of Ammani in bronze. This two-ft high piece of art sits in Paris, freezing Ammani (spelt by Barre as Amany) in a posture from the famous Malapou.

A lithograph shows dancers striking a pose while performing ‘Malapou’

| Photo Credit: British Library

At first, the monochrome Ammani feels rather ordinary in comparison to some of the stunning bronzes that come out of the Indian cire-perdue repertoire. Yet upon closer examination, Barre’s attention to detail is stunning — Ammani’s saree replete with zari checks, and each of her ornaments. Her salangai, oddiyanam and mukoothi are executed in great detail, as is the long flowing braid that slides down her spine. The hallmark of this sculpture is the way in which Jean Auguste Barre captures movement. Ammani is bent completely to the side, but still in control of her spine — a feature that is often lost in our modern practice. Her unusually thin waist was possibly an exaggeration to suit the European aesthetic of the female body. Ammani still stands, mid-dance, in a tiny Museum in Paris, waiting for us to find her.

The Bengaluru-based writer is a dancer and research-scholar.

[ad_2]

Source link