In the lushly produced coffee table book Ganika: In the Visual Culture of the 19th-20th Century India, edited by art historian and curator Seema Bhalla, the world of courtesans comes to life. Over eight essays, including two by Bhalla herself, the book marks the journey of courtesans from the tradition of the devadasi to their representation in post independence popular culture, through depictions in paintings, photographs, films and use of textiles and accessories. Beyond the boundaries of contemporary discourse on courtesans, the book stitches a textured account of their lives and cultural influence, dispelling myths and bringing their artistry into focus.

It began with Devi

The central motivation for the book, says Bhalla, was to offer a more truthful narrative that is not reductive and reflects the reality of the various roles they played in society over time and the footprint they left behind. “While curating an exhibition titled Devi a few years ago, based on Siddhartha Tagore’s art collection, I realised that women are categorised too easily in society. It played heavily on my mind. I wanted to go back in history and see if women were always treated like this?” A clip from the 1966 historical Hindi film Amrapali, directed by Lekh Tandon and starring Sunil Dutt and Vyjayanthimala in the lead was used as a loop in that exhibition. In the film, a king refers to a courtesan Amrapali as ‘Devi’, or goddess. It revealed to Bhalla that there was much more than met the eye, challenging our collective understanding of their cultural legacy.

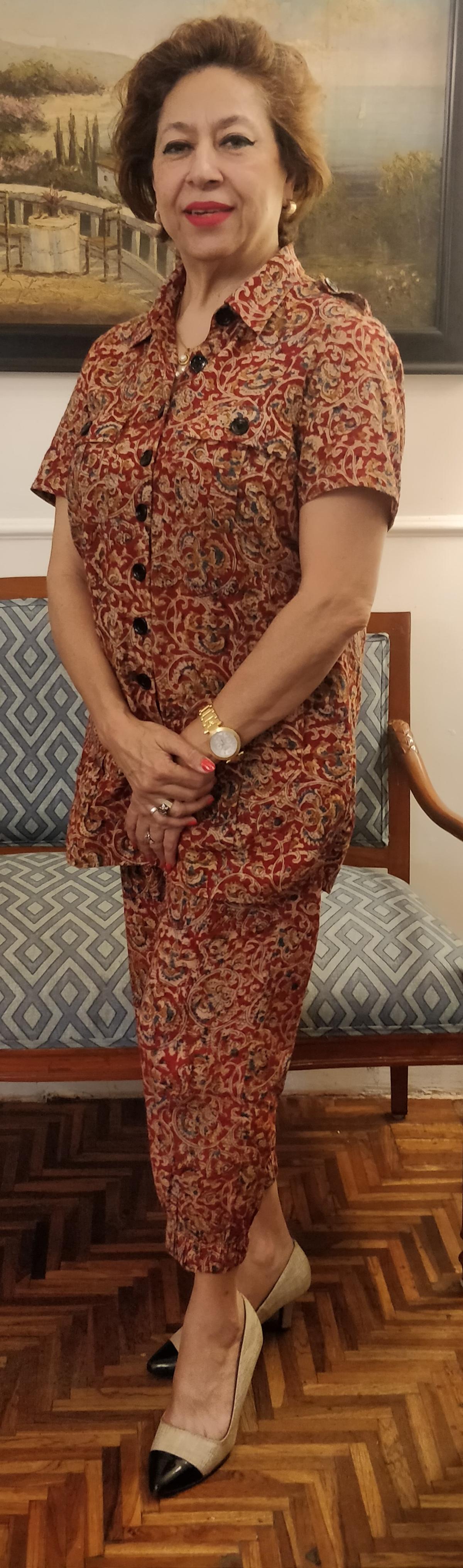

Seema Bhalla

Then came the exhibition Ganika: In the Visual Culture of 19th-20th Century India, based on another collection owned by Tagore, which was displayed at the National Crafts Museum in New Delhi in late 2022. “When I was curating that exhibition, it was clear to me that it had taken a scholarly turn. I decided it deserves a book,” says Bhalla. Every piece of art and photography in the book was part of the original exhibition, but the book was designed as a standalone work.

Hand-held pankhis, a favoured accessory, from National Crafts Museum & Hastkala Academy’s collection

On matchbox covers and cigarette packs

Among the contributors are scholars Ira Bhaskar, Richard Allen, Swarnamalya Ganesh, Shweta Sachdev Jha, Yatindra Mishra, Sumant Batra and AK Das, who explore various dimensions of courtesans’ lives, from art and fashion to dance, music and cinema, contextualised against a backdrop of colonial and postcolonial India. The book’s thematic chapters dive into courtesans’ roles not just as entertainers but as cultural and artistic trend-setters of their time. Some chapters reveal the intersection of art and commerce and how courtesans influenced not just Indian, but global culture.

Indian baizees, show cards inserted in cigarette boxes (19th century, lithograph)

In ‘Nautch Girls: in the Visual Culture of Advertisement’, Bhalla draws our attention to eye-catching images of courtesans adorning matchbox covers and cigarette packs made in countries such as Austria and Sweden, produced for Indian markets. Many such interesting connections between courtesans and popular culture have been forgotten. “Sadly, the ‘Nautch Girls’ of the British era, the Baijis of Bengal, the Naikins of Goa, the Tawaifs of the north, and the Devdasis of the south did not receive a spot of deserving acclaim,” writes Tagore in the book.

Singer-actor Begum Akhtar

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy Yatindra Mishra

The real Heeramandi

In the title essay, Bhalla notes the transition of courtesans from temple dancers to stigmatised figures, diluting their many talents. “Ironically, it is also during British times that the terminology of ‘Nautch Girls’ came into existence. A misrepresentation of the Urdu word, ‘Naach’ became the anglicised ‘Nautch’. Slowly, the ‘dancing girls’, now labelled as nautch girls, became outcasts and the tradition of classical dance that started in temples and reached the courts, was [performed] on the streets,” writes Bhalla. Some depictions, particularly in cinema, have distorted their legacy, too.

Meena Kumari in Pakeezah

With television shows, such as Heeramandi, helmed by filmmaker Sanjay Leela Bhansali, have we managed a deeper understanding of their lives? “Such depictions are larger than life and full of grandeur. Much of it is fiction. For example, the palatial sets of Heeramandi are nothing like the original bazaar that I have visited where the houses are actually tiny,” says Bhalla.

But what is not fiction is that these women were the “original influencers” in fashion, music, and even perfumery, Bhalla says. If she’d like readers to take away one thing from the book, it is that while each chapter delves into a different aspect of their lives through a specific lens, it all comes together to build a full picture, a whole persona. One that spotlights not just the trajectory of the women, but the evolving society that was shaped by them in many ways.

The writer is an author and freelance journalist based in Delhi.

Published – March 13, 2025 05:02 pm IST