[ad_1]

Architects around the world are coming up with new concepts while designing a house for their clients. With people wanting to move out of city limits post-pandemic, and purchasing larger homes in the suburbs, the Japanese concept of Shibusa — intended to evoke appreciation of life — is beginning to trend.

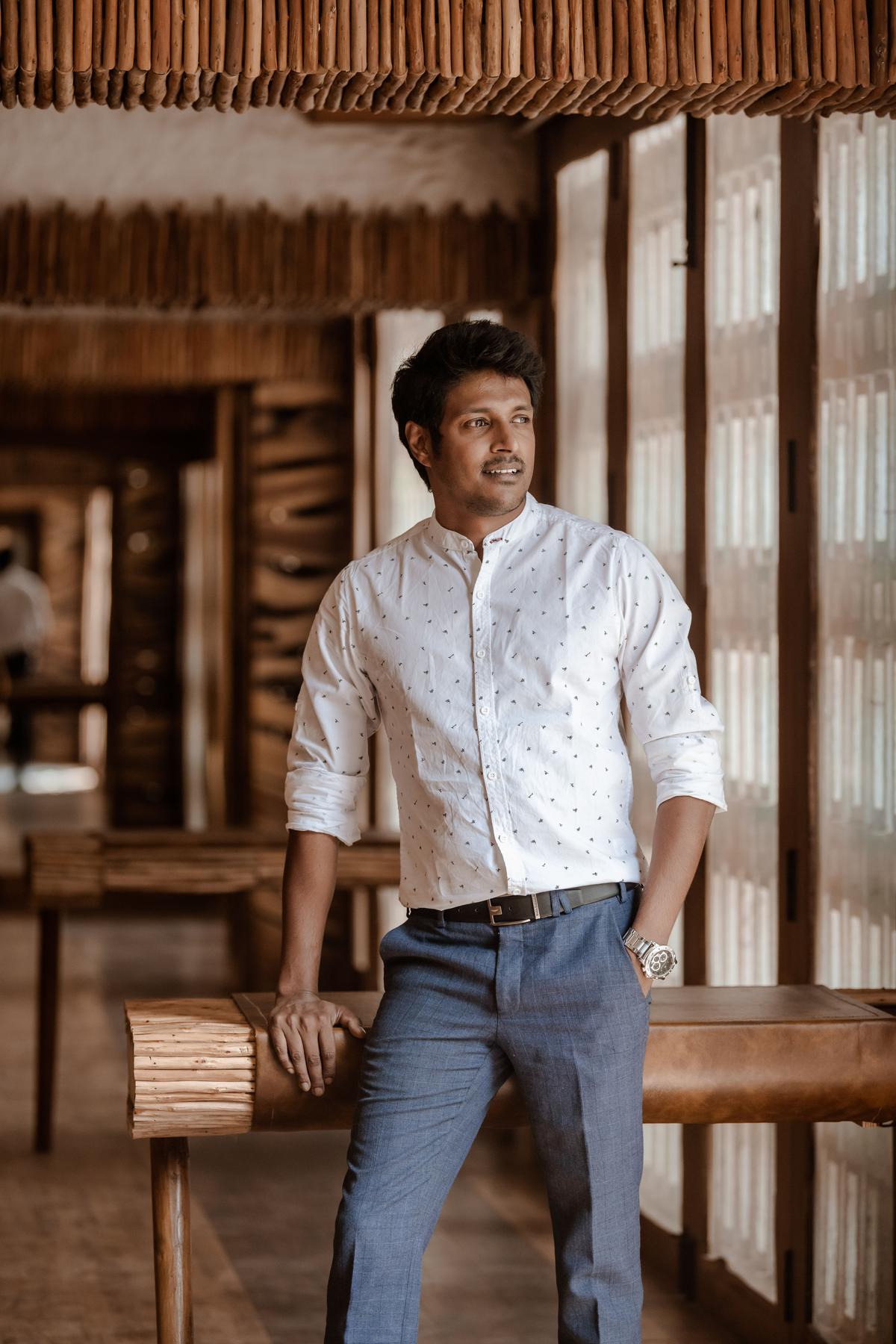

Veeram Shah

| Photo Credit:

special arrangement

When a client approached Veeram Shah, an architect and interior designer, based in Ahmedabad, for designing a house in Baner on the outskirts of Pune, the client asked for practical use of the 2,000 sq.ft. available space.

Viewing his client’s requirements, Shah was sure that Shibusa concept would make it possible. Shibusa refers to simple, subtle, and unobtrusive beauty in affinity with Japanese aesthetics and ideal human behaviour. Even as the architect focused on using natural materials such as wood, other simple materials and textures were also used to cater to a family’s efficient and functional lifestyle. “Since the concept resonated with a designer like me, we went ahead with it,” says Shah.

Veeram Shah’s project in Pune.

| Photo Credit:

special arrangement

The designer tried to reinvent how age-old materials are perceived for a modern Indian home in a market with a plethora of new ones. Wood, brass, cane, lime plaster, concrete, stone, and fluted glass were used for the project based on their earthiness and imperfectly perfect attributes. The project, started in 2019, was completed in 2021.

Small is doable

Shah says the same can be replicated in smaller spaces too. “Most definitely, yes. The beauty of Shibusa, and the concept of this project as a whole, do not lie in the notion of larger square footage. In fact, the concept relies on encouraging users to interact with the surroundings based on their need and not the designated use of the room,” he says.

“In this home, we’ve allowed the kitchen to be a cooking and dining space, while the dining multi-functions as an eating and a working area. Lounging is not limited to the living room but also in the bedrooms for a more relaxed time,” says Shah.

Sustainability is very important for making a Shibusa house, as responsible sourcing forms an essential part of our design process. Shah says, “All the wood used in our projects is reclaimed. Our general inclination is towards using materials that are procured locally and ones that are closer to their natural state. We consciously steer away from merely visually appealing/ ‘synthetic’ spaces. Our focus instead lies in creating spaces that are ‘timeless’, ones that evolve with the user and the social context.”

Architects usually learn from one another and adapt to the changing needs of people. After the COVID-19 lull and work-from-home options being made available, people buying homes out of city limits want to optimise their choice.

Silence and simplicity

Earthitects has a project called Estate Plavu in Wayanad, Kerala. “Estate Plavu is a classic example of how the villa embodies understated elegance, modesty, timelessness, and simplicity of the space with nature,” says George E. Ramapuram, Principal and director at Earthitects. As the Shibusa concept focuses on simplicity and silence, Earthitects’ goal is to create structures that harmonise with the environment, and promote a healthy and sustainable way of living.

Estate Plavu in Wayanad.

| Photo Credit:

special arrangement

Set amid the wilderness of Wayanad, Estate Plavu is inspired by the architecture of mountain bungalows crafted entirely out of natural materials. “Estate Plavu uses wooden flooring, random-rubble walls, cobblestone pathways, and log rafters, showcasing a joyous interplay of stone and wood. The floors, joinery, switchboards, skirting, and furniture are handcrafted with ‘live edge’ teak wood that adorns the spaces with warmth and grain. The wood used in crafting the space portrays its authenticity, with ‘live edges’ accentuating its natural character. Rough, uncut and unpolished stones form the thick random rubble walls of the lodges. Other natural materials portrayed in Earthitects’ Stone Lodges are clay roof tiles, eucalyptus poles in the ceiling, customised-finish granite for counters and stone deck floors,” he says.

George E. Ramapuram

| Photo Credit:

special arrangement

He focused on sourcing materials locally. “Sustainability and innovation should form the heart of any habitable project. For example, the raw materials used in Estate Plavu were sourced either from the same site or locally around Wayanad. Some boulders were cut to form random-rubble walls, while leftover teakwood went into making fixtures and fittings. The greenery and local materials used at the forest site maintain the indoor temperature between 16°C-26°C, a stark difference from the sweltering main city of Wayanad. We have used bird-friendly landscaping here, resulting in 80 species of birds finding homes inside our property,” says Ramapuram.

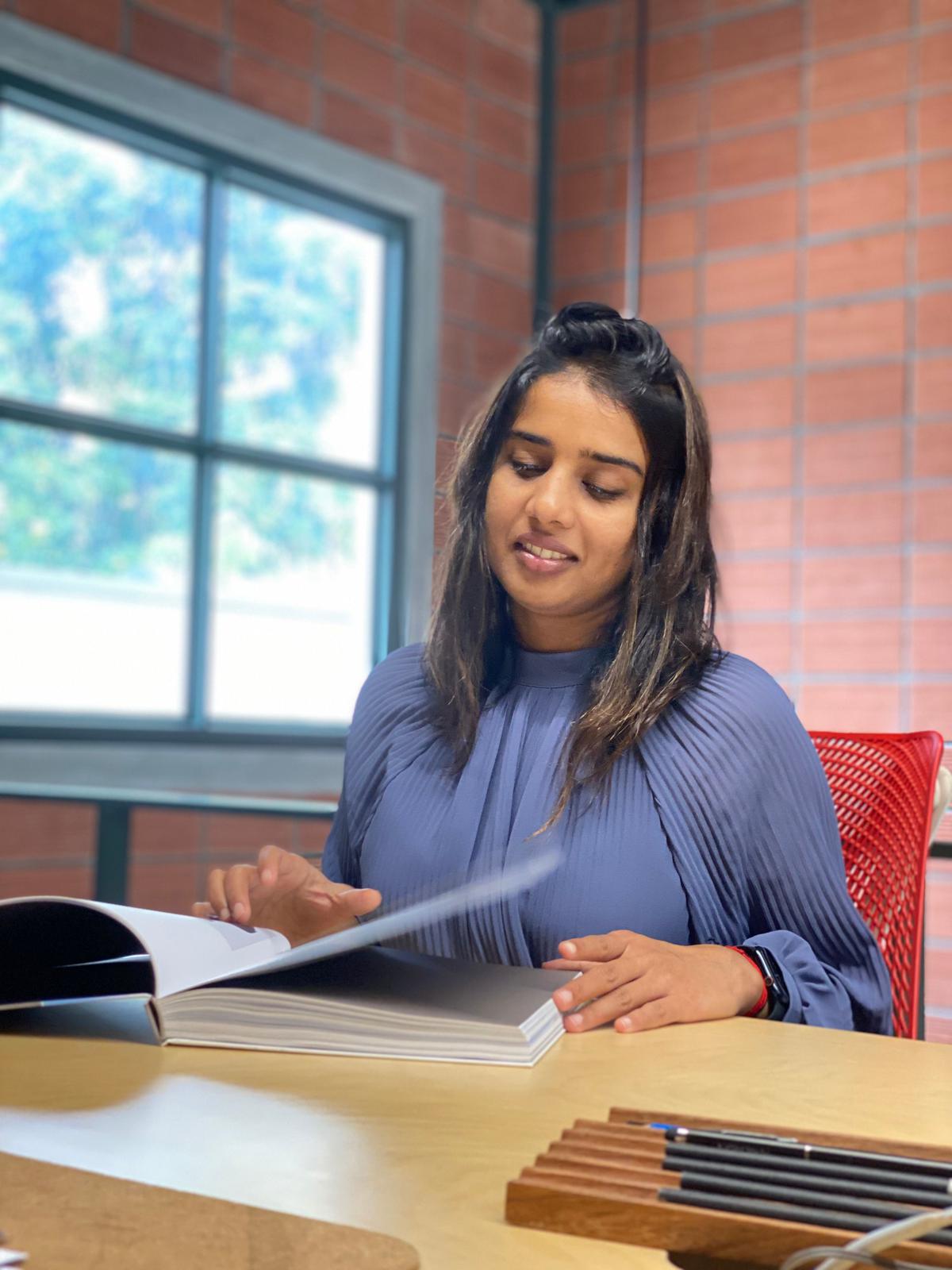

Shalini Chandrashekar

| Photo Credit:

special arrangement

‘Introducing in-situ finishes’

A project not too far from the heart of Bengaluru is Ksaarah, constructed by Taliesyn. “Ksaarah is a weekend retreat that reimagines living in the embrace of nature, while sheltering its inhabitants — a creative professional and her family,” says Shalini Chandrashekar, Principal and director of the company.

For Chandrashekar, spaces act as a bare canvas for self-exploration and self-expression. Talking about the materials used for the project, she says, “Monochromatic concrete and cement finishes blend into the grey background. They are coupled with warm oak wood, which glistens in the sun and softens the architecture. Locally-sourced stones like sadarahalli and pink magadi complete the textural leitmotifs of the residence. This spectrum of materials is pieced together considering that they age gracefully and require minimal maintenance, so surfaces develop a timeless patina over time and merge within the landscape.”

She adds, “Sustainability occurs during the process of building and after the building is built. We recycled materials and used a lot of in-situ finishes to reduce our carbon footprint. Most of the furniture and accessories were passed down from generations, to do away with the need to buy new pieces. Materials were chosen to last long. Stones were sourced locally from nearby quarries; waste stones were recycled into furniture. The khadi bedding and toiletries are all natural. Soft furnishings celebrate traditional Indian craftsmanship, such as kansa crockery. Solar energy powers the entire building. To reduce the need for mechanical air-conditioning, unwanted wall envelopes are negated and are instead replaced with plants and trees. There is optimal, natural air circulation and daylight throughout the day. The pool, designed to catch the flow of the NE-SW breeze, also aids in evaporative cooling and creates a comfortable microclimate on the site. The cellar’s stone walls and the earth filling around it remain cool throughout the year. The pool, without any filtered or added chemicals, doubles up as a storage tank for the vegetation around. Wastewater from the household is recycled and channelled towards farming activities, nurturing the plantations of chikoo, mango and banana trees on the site. Sculptural trees and flowering species are braided into the existing flora, densifying the greenery that will eventually thrive.”

[ad_2]

Source link