[ad_1]

The RBI floated a concept note delving into the risks and benefits of introducing Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) in India as part of their phased implementation strategy

The RBI floated a concept note delving into the risks and benefits of introducing Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) in India as part of their phased implementation strategy

The story so far: Earlier in October, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) floated a concept note enumerating the objectives, choices, benefits and risks of issuing Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDC), or e₹ (digital rupee) in India. The Central Government in March notified the necessary amendments in the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934, paving the way for running a pilot programme and the subsequent issuance of CBDCs.

Broadly, other than fostering financial inclusion and reducing operational costs associated with physical cash management, the e₹ would strive to tackle “rapidly mushrooming cryptocurrencies” which the regulator has on multiple occasions stated can “usher in decentralised finance and disrupt the traditional financial system”.

What is a CBDC? What purpose would it serve?

The apex regulator defines CBDC as a legal tender issued by the central bank in digital form. It would be similar to the sovereign paper currency— albeit digital. Further, e₹ would be accepted as a legal tender and serve as a medium of payment and a safe store of value and would move away from the competitive ‘mining’ of cryptocurrencies to an algorithm-based process. The other features mentioned would accord it greater utility than a crypto-asset.

It would appear as a liability on the central bank’s balance sheet. The prime reasons for exploring CBDC’s use case entail fostering financial inclusion, reducing costs associated with physical cash management and introducing a more resilient and innovative payments system. More importantly, it would provide the general populace an alternative to unregulated cryptocurrencies and theirassociated risks.

The e₹ can be converted to any commercial bank money or cash. It would be a fungible legal tender for which holders need not have a bank account – hence, strengthening the cause of financial inclusion.

What is the prevailing perception about CBDCs outside India?

As per Washington think tank Atlantic Council, 105 countries representing 95% of the global GDP are exploring a CBDC. In fact, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) says that the Asia-Pacific region is at the forefront of introducing digital currencies. Countries like Bangladesh and Maldives, which have not done much research and development about CBDC adoption, areinterested and learning from their peers, as per the IMF.

The rationale for introducing CBDCs vary across countries. However, much of national regulators’ interest stemmed from the surge in crypto uptake observed in 2020-21. Thus, regulators now endeavour to exercise more caution in dealing with volatilities triggered by ‘crypto-busts’ and ‘crypto-winters’, or periods of depressed crypto prices.

Bahamas and Nigeria were the first countries to launch their own CBDCs.

Launched in Oct 2020, the ‘Bahamian Sand Dollar’ is a case in point for financial inclusion. Its primary objective was to serve the unbanked and the under-banked populations across more than thirty of its inhabited islands. On similar lines, East Carribean Central Bank which is the central regulator for Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, Commonwealth of Dominica, Grenada, Montserrat, St Kitts and Nevis and St Vincent and the Grenadines became the first currency union central bank to have a CBDC.

Paper currencies need to physically travel and require certain logistics to be accessible to people. For these distant island nations, CBDCs as a currency would ensure wider geographical coverage. With decidedly lower logistical challenges than paper currency.

Senegal and Ecuador, on the other hand, have opted out of launching CBDCs.

It is not just the smaller countries which are exploring CBDCs. As pointed out by the IMF, 19 G20 countries too are exploring its possibilities. Separately, Asian countries sitting on certain crucial technological advancements would be helped in their CBDC plunge. For example, China’s CBDC project was initiated in 2014 with Singapore and Hong Kong SAR entering the frame in 2016 and 2017.

What are the varied forms of CBDCs?

Based on their usage and functions, CBDCs are categorised into retail (CBDC-R) and wholesale (CBDC-W).

CBDC-R is meant for retail consumption and can be availed by all including the private sector, non-financial consumers and businesses. On the other hand, CBDC-W ismeant for interbank transfers and wholesale transactions by financial institutions.

CBDC-R can be particularly useful for a regulator to ensure financial inclusion. Being digitally based, it can bolster payment mechanisms. On the other hand, CBDC-W can help improve the efficiency of interbank payments or securities settlement, as has been observed in Project Jasper, Canada’s CBDC project, as well as Project Ubin— Singapore’s CBDC project.

Now coming to the question of accessibility; in other words— how the asset would flow in the supply chain. The two suggested model types are the token-based system and the account-based system.

The former would flow into circulation like a banknote and can be electronically transferred from one entity to another. Token ownership is prima face verified— the possessor of e₹ is by default deemed as its owner, just like banknotes. Only the authenticity of the token is to be verified.

In contrast, the account-based system would require the payer to verify that he has the authority to use the account and in possession of sufficient balance to carry forth a transaction – similar to existing digital transaction methods. It requires maintaining a record of balances and transactions of all holders of the CBDC and indicate his/her ownership of monetary balances.

What would the ‘supply chain’ be like?

The previously-illustrated distribution model could potentially be integrated to either the single-tier or the double-tier model.

As the name might suggest, in the Direct CBDC system the central bank manages the entire supply chain from issuing CBDCs, to maintaining accounts and verifying transactions. Its server is involved in all payments.

The double-tier model adds to the supply chain the role of an intermediary (or a service provider). This supply chain is further categorised into two, namely, the indirect model and the hybrid model.

The indirect model entails consumers holding an account/wallet with a bank, or service provider. The obligation to provide CBDCs to retail customers would fall on the service provider and not the central bank. The latter would only be involved in ensuring that the wholesale balance is identical to the retail balances of its retail customers; in other words, scrutinising whether the CBDCs being given to retail customers are equivalent to what the intermediaries have been allocated.

In contrast, while the intermediary handles retail payments in the hybrid model, the central bank provides CBDCs directly through intermediaries. In other words, the central bank as well as the intermediaries maintain the ledger of all transactions and manage payments. The regulator would operate a backup technical infrastructure allowing it to restart the payment system if intermediaries run into insolvency or technical outages.

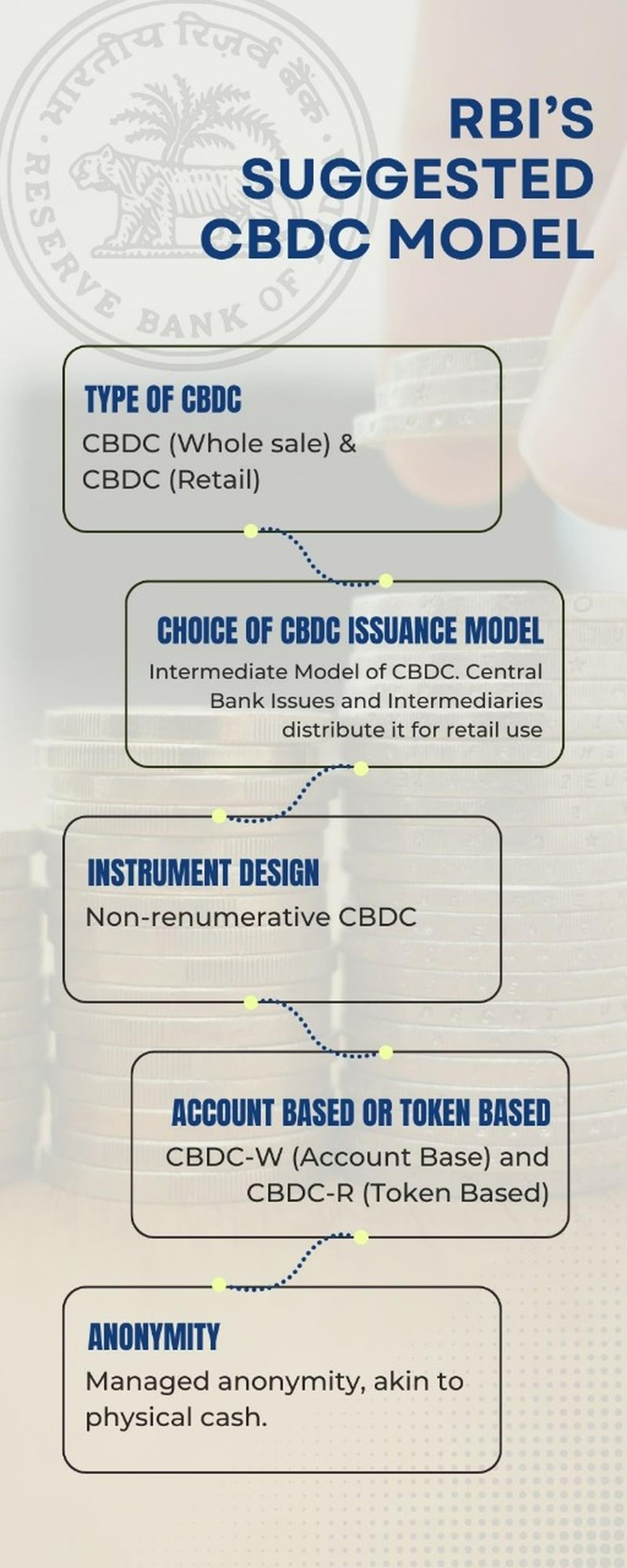

What models does the RBI deem suitable?

The RBI deems the indirect model more suitable for India, with the central bank creating and issuing tokens to authorised entities called Token Service Providers (TSPs). These TSPs would then distribute the tokens to end-users who undertake retail transactions.

The regulator acknowledges that it may not have a comparative and competitive advantage over banks in distribution, account-keeping and customer verification, among others. This is especially in an environment where technology is rapidly changing.

Further, it deems CBDC-W suitable for account-based transactions and CBDC-R for token-based transactions. Issuing CBDC-R in a token-based system would help the regulator with its financial inclusion goals. Additionally, CBDC-W in an account-based system would facilitate instant settlement with a well-established legal status as transactions would emanate from verified accounts.

Does the concept note point to certain challenges?

The concept note highlighted certain concerns pertaining to data collection and anonymity, cyber-security, dispute resolution and accountability.

About concerns pertaining to data collection and anonymity, the apex regulator notes that there emerges a possibility that anonymous digital currency would facilitate a shadow economy and illegal transactions. Regulators require insight to identify suspicious transactions, such as those pertaining to money laundering and terrorism financing, among others. Addressing this concern, the IMF recommends instituting a specific threshold (say $10,000) for regulatory oversight.

The apex regulator recognises there is an increased probability of payment-related frauds in countries with lower financial literacy levels. It states the ecosystem would be a “high-value target” since it is important to maintain public trust. Ensuring financial literacy and cyber-security thus becomes very important.

CBDCs would also need infrastructure for facilitating offline transactions. The risk of ‘double spending’ is spurred when operations head offline. This is because a CBDC unit could potentially be used more than once with the ledger requiring an internet connection to update. However, RBI believes it could be mitigated to a large extent by technical solutions and imposing limits on offline transactions. It acknowledges the importance of enhancing offline capabilities for wider use, pointing to only 825 million of a total population of 1.40 billion having internet access in India.

RBI would also explore the possibility of cross-border payments using CBDCs. In a related context, the IMF has observed that fragmented international efforts to build CBDCs would likely result in interoperability challenges and cross-border security risks. “Countries are understandably focussed on domestic use, with too little thought for cross-border regulation, interoperability and standard-setting,” it said.

And lastly, financial implications would be difficult to ascertain considering that the potential demand would be subject to the implementation framework. However, RBI highlights two broad concerns in the event of a financial crisis. There could either be a potential ‘bank run’, in other words, people withdraw their money rapidly from banks, or a financial disintermediation that would prompt banks to rely on more expensive and less stable sources of funding.

The switch from cash to CBDC might just be a transition from one asset to another and might not impact the banking sector’s balance sheet. Similarly, as per the RBI, a switch from deposits to CBDC would shrink the balance sheet similar to withdrawal of banknotes from an ATM or branch.

However, should a bank’s reserves fall below its ability to meet supervisory liquidity measures, the central regulatory bank might be required to inject some liquidity.

[ad_2]

Source link