[ad_1]

JNU VC Santishree Dhulipudi Pandit on why she is agonised by its anti-national image, the problems of standardising the admission process and what makes JNU India’s premier academic institution. The session was moderated by Sukrita Baruah, senior correspondent

Sukrita Baruah: Would you like to begin with a few opening remarks?

Jawaharlal Nehru University, by all ratings, both government and private, is India’s number one institution. It represents what I call the D-five: Democracy, Development, Difference, Dissent and Diversity. I would also say that I’m very concerned, being a JNU-ite myself, that the real image of JNU has to be represented by the people who have made it the number one university rather than by the lunatic fringe. We represent tradition with modernity, realm with region and change with continuity — we are the only university that is all India. We still have fees at Rs 10 rupees and Rs 20 — no other institute of higher learning can match us on this. So, if any government talks about inclusion, with equity and excellence, Jawaharlal Nehru University is the best example of sabke saath, sabka vikas.

Sukrita Baruah: When you took charge, the first statement issued by your office said that the focus would be on ‘constructing Indo-centric narratives.’ Could you explain what you meant by that?

I think all universities have to be open to all narratives. I’m not against any narrative as long as everybody has a space. That’s why I said I’m for dissent, difference and diversity. I’m not saying that this is good, or that is bad. There has to be an acceptance of multiple narratives. You can’t have hegemony of only one narrative. Unfortunately, in JNU, there is no space for others. So, I say ignorance cannot be the starting point. Let us widen our areas, bring in new perspectives, each from their own regions, or even from different ideologies. Truth may be one but there are several paths to it is our motto — ekam sat vipraha badhuda vandanti. I’m just saying open up all the paths.

Sukrita Baruah: In the last three-four years, we’ve seen a lot of animosity between the JNU administration, students, student representatives, and even teacher representatives. Is that something that you think needs to be addressed urgently?

When I had joined, the atmosphere was very suspicious of anybody being appointed by the government. But after they saw me, they knew that there are also different people. My office is open to any faculty or student any time of the day. I visit hostels, I have food with them. I think there is always a way of resolution. We can agree to disagree, there is no harm in it, but there may not be any animosity. I think that has worked. Let me also give credit to both the faculty and the students. I’ve told them I don’t see people through ideological lenses. Everybody is a JNU-ite, first and last. As long as you’re a part of this community, we are an epistemic community. That is how JNU should be. This is a space that has to be more liberating as well as invigorating, intellectually and otherwise.

Ritika Chopra: You spoke of the hegemony of one narrative and a lunatic fringe which seems to be influencing the image of the university. Could you elaborate on that?

The Left has been dominant in JNU and they’ve done very good work. But the problem comes when they say other narratives cannot exist. There has been systematic discrimination on those who differ. Indian history is only Romila Thapar and Bipan Chandra. But there is RC Majumdar, Jadunath Sarkar, Nilakanta Sastri — all of them have been thrown out. This type of exclusion creates problems not only for them, for the other side also. I don’t want to do reverse discrimination. I am asking for coexistence of all. All of us have multiple identities, and I can project any identity just by context and circumstances. Every university has a lunatic fringe. There are troublemakers, they can be left, right, centre, anything. But they cannot define the identity of the university.

See JNU was made to look anti-national, urban Naxal, tukde-tukde gang Please give me a break. There are three ministers in the present cabinet who are alumni of JNU. Seventy per cent of the bureaucracy is from the University, and, even in academia, I think 50 per cent. When we are contributing to the nation, how are we anti-national? I would not say the lunatic fringe is from any ideology, It is those who believe in creating disturbance and violence for the sake of violence. JNU cannot be penalised because of that group. You would have seen recently in Parliament, all other top universities in the top 10 or top 20 got eminence grants of Rs 1,000 crore. Their budget has increased three times. The least increase was for JNU. Why are we not given as much? We are the best not only by outside ratings but by the government’s ratings, too. When you give us ratings, give us money as well. Today, we are running at Rs 130 crore deficit. You can’t do this to an institution you rate as number one. One of the goals of NEP is critical thinking. JNU, being the best, can do it better.

Ritika Chopra: Do you feel that that image influenced the government?

I’d only say that the leadership in JNU must place it properly. It’s been seven months since I’ve come. The government is very receptive. I was able to get Rs 56 crore, thanks to Smt Nirmala Sitharaman, who’s a former student of JNU and my senior, and the minister, Shri Dharmendra Pradhan. We didn’t even apply for the eminence. How will the government even consider us?

Ritika Chopra: You did not apply for the eminence status?

I’m going to do it, earlier we didn’t. See, it is my job to represent the university in a positive light — I’m also a product of JNU. So, if I’m (called) anti national, I feel very hurt because this university has given me what I am today. I think earlier administrations should have done it. I wouldn’t blame the government. Most of our faculty are doing wonderful work and they’re as nationalistic as anybody else in this country.

Vandita Mishra: Many senior people in government have actually propagated this tukde-tukde or anti-national image. How do you then go to the same government for funds?

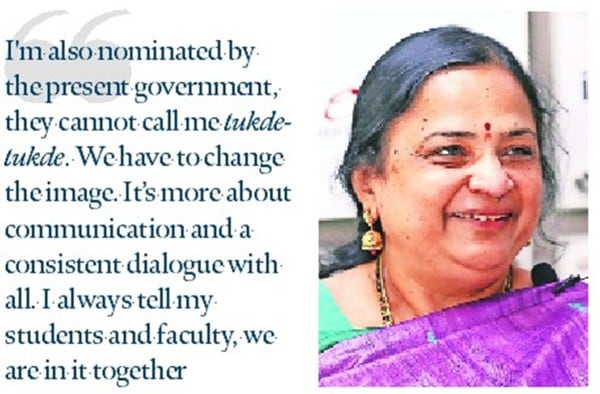

I’m also nominated by the present government, so they cannot call me tukde-tukde. We have to change the image. It’s more about communication and a consistent dialogue with all. I always tell my students and faculty, we are in it together, you are also part of the solution as much as the problem. So, don’t see me on the other side.

JNU is unlike other central universities. Thanks to Mrs Indira Gandhi, we have a separate Act of Parliament, and we are the only university that can affiliate anywhere in India. I have recommendations for institutions to go to JNU because a degree from JNU will give you international recognition. This is a huge change. I come from the social sciences and I think we perform better with a humane approach. I have a daughter who’s an engineer. She thinks why is the world unfair. Every time she asks me, I tell her that is the reality. But she says no. She writes an algorithm in cyber security and she thinks the result has to come out. But we are dealing with human beings, everybody is different. We have to be considerate, empathetic. Human beings are complex and every human being is different. Technology is an instrument in the hands of superior minds and we can see how Prime Minister Modi’s vision and mission makes the difference not the reverse.

Harish Damodaran: There’s been this huge trend of children going abroad to study, including undergrads. What explains this? Like you said, JNU has an international reputation. So why are people leaving this public-sector education system? And within India, going towards the Ashokas and Azim Premjis (private universities)?

It’s an important question. First, we still spend only 3 or 3.2 per cent of our GDP on education, which is very low. If we want to implement the NEP 2020 as visualised, you’d need to go to at least 6 per cent. So, we are not making our existing educational institutions attractive. The problem is we can admit only 10,000 students and there is one to one lakh (applications). Where will the others go? We haven’t thought of that.

Other than merit, we look at every other identity. That is a reality, we have to accept it — it is part of electoral politics, part of everything. I won’t mind economic backwardness as a reservation, but then identity politics sometimes can go overboard. This is a problem where you have very good people who, when they don’t get (in), have the wherewithal to go abroad and they would like to go. If we want to compete, we will have to increase the number of public institutions like JNU, especially for the poor. Ashoka, Jindal and others is where you pay in lakhs, which I don’t think everybody can.

You would have seen the recent global gender gap report of 2022, which says that the labour market is still a boys’ club. Can you believe, in a university like JNU, I’m the first woman vice chancellor and the first one from the social sciences? You’ll see the domination of science and technology, which also is not very good. If you want holistic education, you have to have all disciplines.

I would say (that) like South Korea or the Southeast Asian countries, 15 per cent of GDP must be invested in education and health. Unless you do that, we are not going to make any real progress where we can compete with the best, especially the West.

Harish Damodaran: With all the inadequacies you pointed out, the fact is JNU was contributing some of the best minds to bureaucracy, media, etc. Do you still see JNU as producing the best minds in various disciplines?

I think JNU still has the best. In my five years, I have over 350 appointments in my hand. There is no interference from any governmental or other agency so far. I’ve made it very clear, academic merit is first. So, these 350, we will try to get the best.

We can assure you that even in ranking, we are still on top. The only thing is we need much more funds to come into JNU. We are looking to other places, but we are also appealing to the government. You know Adnan Sami’s song, Mujh ko bhi toh lift kara de? You’ve given to so many people, give us also. The highest they’re giving is Rs 1,300 crore, an admission by the Minister of State in Parliament. JNU gets just Rs 470 crore and we beat them hollow in ranking. I’m not saying stop giving them — mujh ko bhi lift kara do, mujhe bhi 1,300 crore de do, 1,000 crore de do. I have to pay my contractual workers. JNU will live up to its expectations, at least in the five years I’m there because I’m a product of this university. I love the place.

Aakash Joshi: You touched on less autonomy or more standardisation in admission processes across universities. Do you think that is going to be a problem, particularly for postgraduate courses where there is a degree of specialisation or, at least, a degree of interest that, under normal circumstances, faculty and administration would have been able to judge?

The Pied Piper will call the tune. 100 per cent of our budget comes from the central government. So we are under the CCS rules whether we like it or not. I would agree partially with you, at least in Master’s you cannot have admission on MCQs alone because we don’t even know whether the student can write anything. For PhD, we have been able to convince the government that everything cannot be MCQs (multiple choice questions). So, 70 per cent will be there, there will be a 30 per cent interview, and JNU will do it. This is in keeping with the vision of NEP 2020 about holistic, inclusive education with critical thinking.

Ritika chopra: You said you have urged the government to change the format. For whatever reason, they didn’t. Would JNU want to continue taking in students through CUET-PG?

We have no option. We are a central government university and our funding comes from the central government. This acceptance to join it was done by the previous administration. I support the concept of a national test. Many of our teachers have opposed this MCQ format, especially in the Social Sciences, Humanities and Languages. A very major criticism has come from our faculty and, in the Indic tradition, the guru is respected and his/her views taken seriously.

Raj Kamal Jha: You said you weren’t there when the previous administration accepted the MCQs. If you would have been there, would you have opposed, put your foot down?

If I was there, I would put these concerns in writing because it’s very important that we tell the government. It is important that as a teacher and as stakeholders within the system, we have to make the government understand that these are the difficulties that we have in reality. We are not opposing the system per se, but the implementation can be disastrous if we are going to have this type of uniformity. Social Sciences, Humanities and Languages get the bulk of the students. The whole debate on fact versus value, the limitations of the quantitative testing has been accepted in the ’70s and ’80s in the West. India is very diverse, we can’t have this uniformity. I’m against one identity being imposed on any part of the country because this will kill creativity and innovation. This also goes against the values of the Indian knowledge systems that celebrate cultural diversity and intellectual excellence.

Unni Rajen Shanker: You spoke about five years and 350 appointments, you will get the best talent. Have you looked at the last six years’ appointments? Are you happy?

I don’t think I can make a public statement as I was not there. We will maintain the highest traditions of excellence and brilliance. I don’t think we will discriminate against anyone to the best of our abilities. That’s why I’ve opened up all the reserved category backlogs. We are opening up other positions which have not been filled.

VANDITA MISHRA: As you make appointments going forward, along with merit, there may also be political pressure for accommodating people who feel that they were left out of these spaces earlier. How do you propose to tackle that?

Let me compliment the Minister Shri Dharmanendra Pradhan and his ministry, there has been no interference. The Minister respects autonomy of higher education institutions. In my hierarchy of priorities, the first would be academic merit. If the person is qualified, then other things can be considered. But when the person is not at all qualified, there’s no question of ideology. The government is also smart. They know whom they can push around and whom they cannot. So far, let me give credit to the government, I have got no instructions. My benchmark would be research and academic excellence. If the person is really good, there’s nothing else that I would look at. I think the government also will endorse it. When you want to become a vishwaguru (world teacher), you can’t exclude people. I think the government will and is practising sab ka saath, sabka vikas, sab ka prayas and sab ka vishwas.

Ritika Chopra: You had earlier suggested that when you joined as JNU VC you faced challenges that were carried over from the previous administration. Your predecessor (M Jagadesh Kumar) now heads the University Grants Commissiom (UGC) which oversees the university system in the country. As JNU V-C, how has your working relationship been with him?

The UGC comes under the Ministry of Education. It doesn’t even have the powers now to give positions. Grants and the rest come from the Ministry of Finance and Ministry of Education. I don’t think we have had any major differences so far. UGC chairman has also not interfered with JNU. It’d be wrong for me to be judgemental.

Newsletter | Click to get the day’s best explainers in your inbox

Vaidyanathan Iyer: One of your own students, Umar Khalid, has been in jail for almost two years. How do you look at this issue? Would you have handled it differently? Do you see a red line that will keep the police out of the campus?

I would resist inviting police onto the campus because that is a clear indication that I have failed in my leadership. The minute a case becomes a legal issue, the university has very little to do. It is determined by the politics or the ways the state is run. JNU creates two delusions. One is that everything is free. Two, that any action has no consequence. Please understand the choices you make have consequences. So when you’re making a choice, you should know what are the consequences. One thing I keep telling students, freedom brings responsibility. So if you want to do it, think 10 times about the consequences. Authority seldom gets into much trouble, but it is you, young people, who do.

!function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s)

{if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function(){n.callMethod?

n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments)};

if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version=’2.0′;

n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0;

t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0];

s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)}(window, document,’script’,

‘https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js’);

fbq(‘init’, ‘444470064056909’);

fbq(‘track’, ‘PageView’);

[ad_2]

Source link