Chef Leo believes in highlighting ingredients such as Santander ants, mojojoy Amazonian larvae and pirarucú river fish that make the invisible visible

Chef Leo believes in highlighting ingredients such as Santander ants, mojojoy Amazonian larvae and pirarucú river fish that make the invisible visible

Colombian chef and social entrepreneur Leonor Espinosa, also known as ‘Leo’, believes in using gastronomy as a vehicle for social and economic development in indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities. Her skill lies in weaving ancestral culinary knowledge from rural communities into contemporary and mainstream food ethos. Known for her ‘ciclo-bioma’ philosophy that highlights the culinary biodiversity of each biome, the 59-year-old is a regular on national TV in her country and promotes Colombia as a ‘gastronomy tourism destination’ abroad.

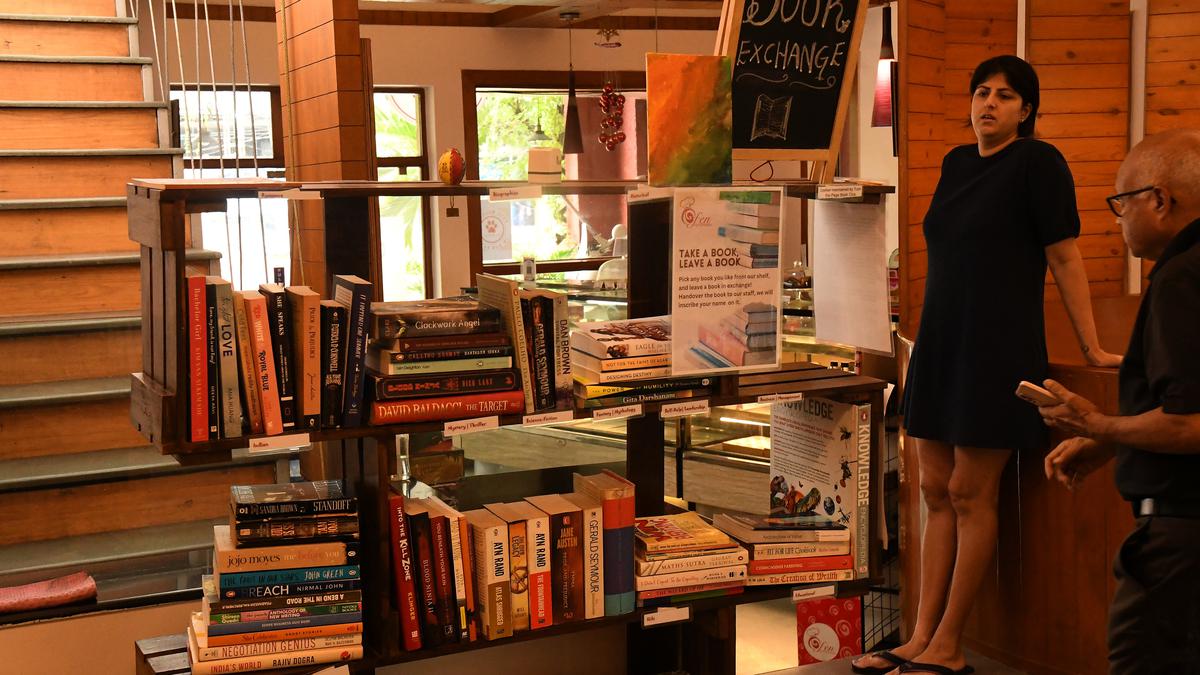

Leonor Espinosa (right) runs her Bogotá-based restaurant, Leo, with her daughter, sommelier Laura Hernández-Espinosa.

| Photo Credit: Special Arrangement

She was recently voted World’s Best Female Chef 2022 by the panel that elects The World’s 50 Best Restaurants. Her Bogotá-based restaurant, Leo — which she runs with her daughter, sommelier Laura Hernández-Espinosa — was listed in The World’s and Latin America’s 50 Best awards. She was also a recipient of Latin America’s Best Female Chef award, and the Basque Culinary World Prize, both in 2017, for her socio-environmental foundation, FUNLEO, that reintroduces ancestral culinary knowledge from Colombia’s rural communities into mainstream gastronomic culture.

A former advertising executive, she gave up corporate life to begin her culinary journey, working with marginalised farmers and highlighting indigenous ingredients such as Santander ants, mojojoy Amazonian larvae and pirarucú river fish. Edited excerpts from an interview:

How did you come to be a chef?

I started cooking at the age of 35, at an age that made me understand cooking as an interdisciplinary profession. In my youth, I studied economics and fine arts, working for almost a decade in advertising. At one point, I made a stop and decided to return to art based on historical memories and my own experiences.

From this new beginning, the kitchen began to emerge as a place for me to investigate, observe and experiment. Thanks to gastronomy, I managed to connect with my roots, the hidden stories and a past full of traditions. Undoubtedly, the kitchen is something that, by tradition and experience, is preserved in memory — an identity which revolves around your childhood.

My greatest inspiration and motivation have been the world views and cosmogonies of the ethnic world around me.

Some of Chef Leo’s creations that highlight the produce of the land.

| Photo Credit: Special Arrangement

Some of Chef Leo’s creations that highlight the produce of the land.

| Photo Credit: Special Arrangement

What are some of your fondest childhood memories of food?

The memories are varied. I dream of the moments shared with family and friends, especially on my maternal grandmother’s farm. Everything revolved around crossing the rivers. And something that was always central to our lives was the wood stove in my grandmother’s country house. Among my most pleasant memories are those of a huge table lined with plantain leaves and laden with succulent preparations — from hares, rice, corn to buns and roast meats. We served to please our palates. I have shared many such memories in my 2018 book, Lo Que Cuenta El Caldero ( Tales From a Cooking Pot).

What was the idea behind your restaurant, Leo?

Leo was born in July 2005, as a result of my interest in making our gastronomic heritage and the potential of our natural wealth visible. At the same time, to show the narratives of our lands, of our diverse cultures and traditions, and to deliver a mixed identity of ancestral knowledge to the palate of our guests.

The menu is constantly evolving, reaffirming each cultural context depending on the ingredient used. It is also recreating an identity based on the knowledge of culinary historical memories behind each product. About 90% of the ingredients come from areas that are difficult to access, are not available in common markets and are little known by the consumer in general. We work directly with producers from different regions of the country, we do not have intermediaries, and part of our objective is to strengthen the work of the Afro-indigenous and farmer communities with whom we cooperate. In its entirety, Leo uses ingredients in a responsible and circular way trying to minimise waste.

At her restaurant, Chef Leo uses ingredients in a responsible and circular way trying to minimise waste.

| Photo Credit: Special Arrangement

How does your ‘ciclo-bioma’ philosophy use gastronomy for social and economic development in indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities?

Innovation and vindication of our traditions are the fundamental aspects of ‘ciclo-bioma’, highlighting the culinary biodiversity of each territory, and the contexts and stories behind each culture. Ciclo-bioma represents change, innovation according to tradition, constantly mutating and renewing itself.

Cooking is also a political act that is closely related to the production of food, especially when factors such as climate change, deforestation, exploitation of natural resources, wars, monopolies, among others, affect sovereignty and food security and local consumption. In this way, it participates in the reduction of existing economic and social conflicts to deal with the terrible production, trade and consumption policies that our society faces. We are relevant actors in the production chain, our greatest social commitment is to support ancestral cultural knowledge and ethnic identity. For instance, take the way we use leaves as wraps in Colombian cuisine — there are more than 150 leaf species that are used to create tamale-like parcels in various dishes. For me, using the leaf (and its gastronomic by-products) is a way of making the invisible visible.

The writer is a freelance journalist exploring the intersectionality of environment, gender, and food.