To the East India Company and the British Raj that followed it, mapping was an obsession. The empires that came before them, such as the Mughal and the Marathas, did not engage in cartography in quite the same way.

The British needed to study the topography of what was to them very foreign territory in order to assess revenues from rent-farming in the subcontinent. The result was survey maps, which were among the earliest efforts to document the country as a whole. Through these maps, for the first time, India emerges as we recognise it today. These give us an idea of how splintered we once were and how we have moved ahead, shaped by many forces, to become a unified whole.

South’s inflection point

A study of some of the historic maps in the Sarmaya collection reveals how, once, even a cohesive Deccan and the Coromandel seems to have been a distant possibility. A map from 1758 by Jacques-Nicholas Bellin reveals the inflection point in the history of South India.

South India and Ceylon, 1758 (Jacques-Nicholas Bellin; print on paper)

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy of Sarmaya Arts Foundation

The map has just about every empire represented: the Carnatic, with its Nawab, is a huge presence, and huddled against the coast are the colonial powers stretching from the present Andhra border all the way to Kanyakumari. What is today just one state, namely Tamil Nadu, has the Dutch (Pulicat, Sadras, Nagapattinam), the British (Madras, Fort St David at Cuddalore), the remnants of the Portuguese (San Thome is listed separately), and the Danes (Tharangampadi). At this stage, though the game was still wide open, the British had begun to emerge as the strongest contenders to the seat of power in south India.

British obsession with Tipu Sultan

Soon, however, British ascendancy was challenged by Hyder Ali, the de facto ruler of Mysore. By the 1760s, all attention was centred on how to tackle him. What followed was a series of four wars, spanning three decades. The first Anglo-Mysore War was decisively won by Hyder Ali but his death in 1782 meant the second one was inconclusive.

He was succeeded to the throne by his son Tipu Sultan, who commanded even greater fear among the British. In Madras, English traders rarely ventured out of Fort St George, such being the terror that Tipu struck. In 1782, he had come up to the Fort and threatened the Governor’s bungalow on Mount Road.

East view of seringapatam (John William and Robert H Colebrook, 1793; monochrome engraving on paper)

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy of Sarmaya Arts Foundation

Several maps show the British obsession with Tipu Sultan. In 1792, in the third Anglo Mysore war, the Governor-General of India Charles Cornwallis defeated him and imposed war damages. Tipu’s sons were taken hostage, brought to Madras and kept there till the money was paid. Given their respect for Tipu Sultan as an adversary, this victory was very important for the British to commemorate. In paintings and sculpture, artists of the time recreated the moment. The scene when Lord Cornwallis took the two sons from Tipu Sultan is carved into the frieze under the statue of Cornwallis at the Fort Museum in Madras.

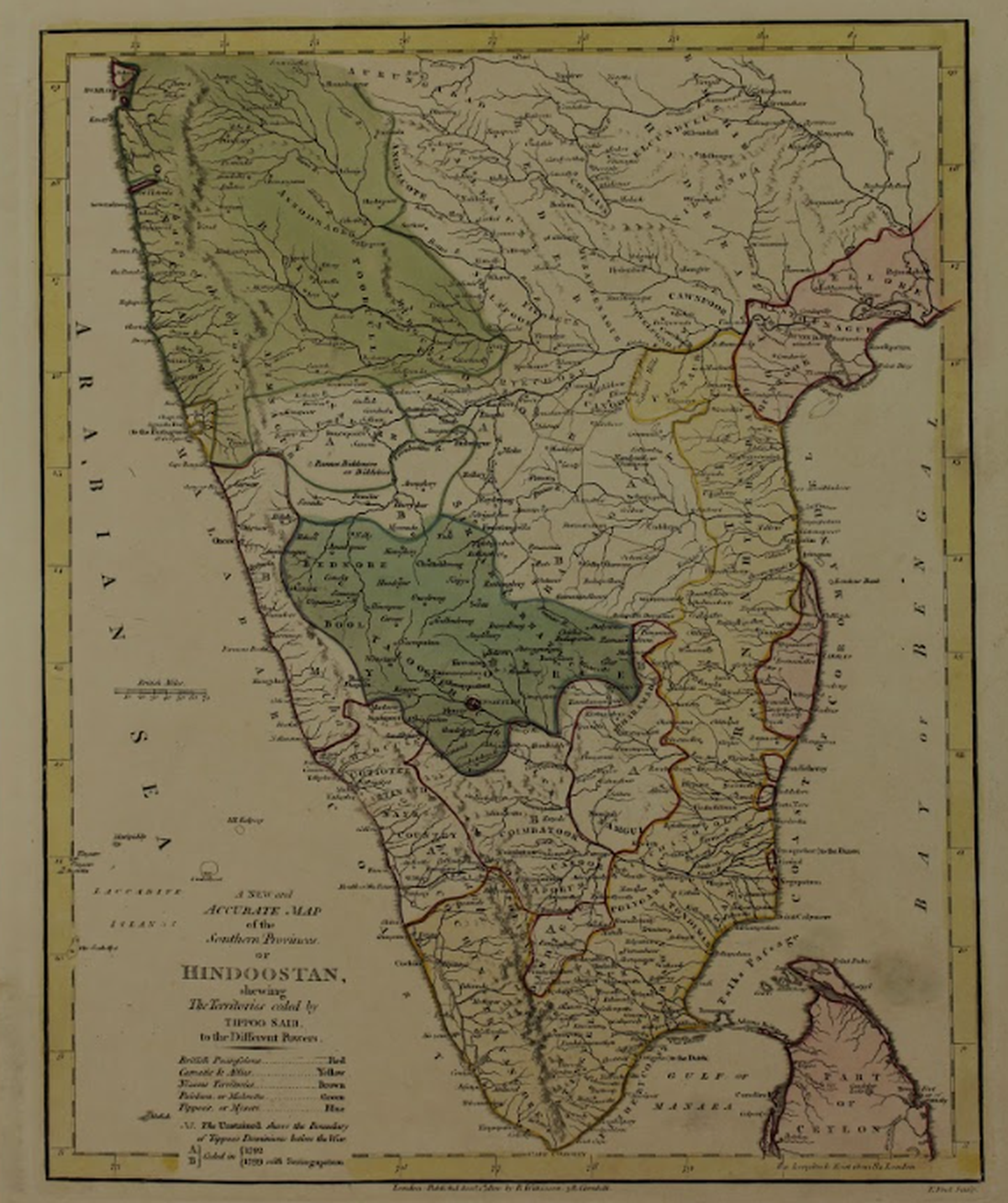

A new and accurate map of the Southern Provinces of Hindoostan showing the territories ceded by Tippoo Sultan to the different powers, 1800 (Robert Wilkinson, T. Foot; print on paper)

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy of Sarmaya Arts Foundation

In time, Tipu repaid damages and took back his sons. But he and the kingdom of Mysore were now much weakened and in no position to take on the British. Then the battle came to his doorstep.

Art of battle

The last stand of Tipu Sultan, the storming of Seringapatam and the discovery of his body are all gripping action paintings, recreated by artists from first-hand accounts of eyewitnesses. The most decorated among these was Colonel Arthur Wellesley, who was sent in 1798 by his brother and then Governor-General Richard Wellesley to stir up war with Mysore.

A triptuch of the storming of Seringapatanam, 1802-1803 (Giovanni Vendramini, Tinted Mezzotint)

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy of Sarmaya Arts Foundation

It was claimed that Tipu had sought help from Napoleon, who had by then reached Egypt, and urged the French to attack the British in Madras. To prevent this, the British, the Marathas and the Nizam of Hyderabad formed an alliance against Tipu. The fourth and final Anglo-Mysore war ended with the siege of Seringapatam (Srirangapatna), which lasted through April and May in 1799. Tipu may not have wanted to fight but in the end, he emerged. And perished.

Defeat of Tippoo Saib before Seringapatnam (Marquis Cornwallis, 1795)

| Photo Credit:

Courtesy of Sarmaya Arts Foundation

The fall of Tipu marked the rise of Arthur Wellesley, who went on to greater glories in his career. He distinguished himself at the Battle of Assaye against the Marathas, defeated Napoleon at Waterloo and became the Prime Minister of England twice. He was made Duke of Wellington, and Wellington cantonment in the Nilgiris is named for him. One last map makes for poignant viewing. It shows us how the Nizam, the Marathas and the East India Company carved up Tipu’s territory. An era had ended, and the British were all set for a lasting tenure as overlords.

The columnist is a writer and historian.

The last in the series of columns by sarmaya.in, a digital archive of India’s diverse histories and artistic traditions.

Published – March 07, 2025 03:09 pm IST