[ad_1]

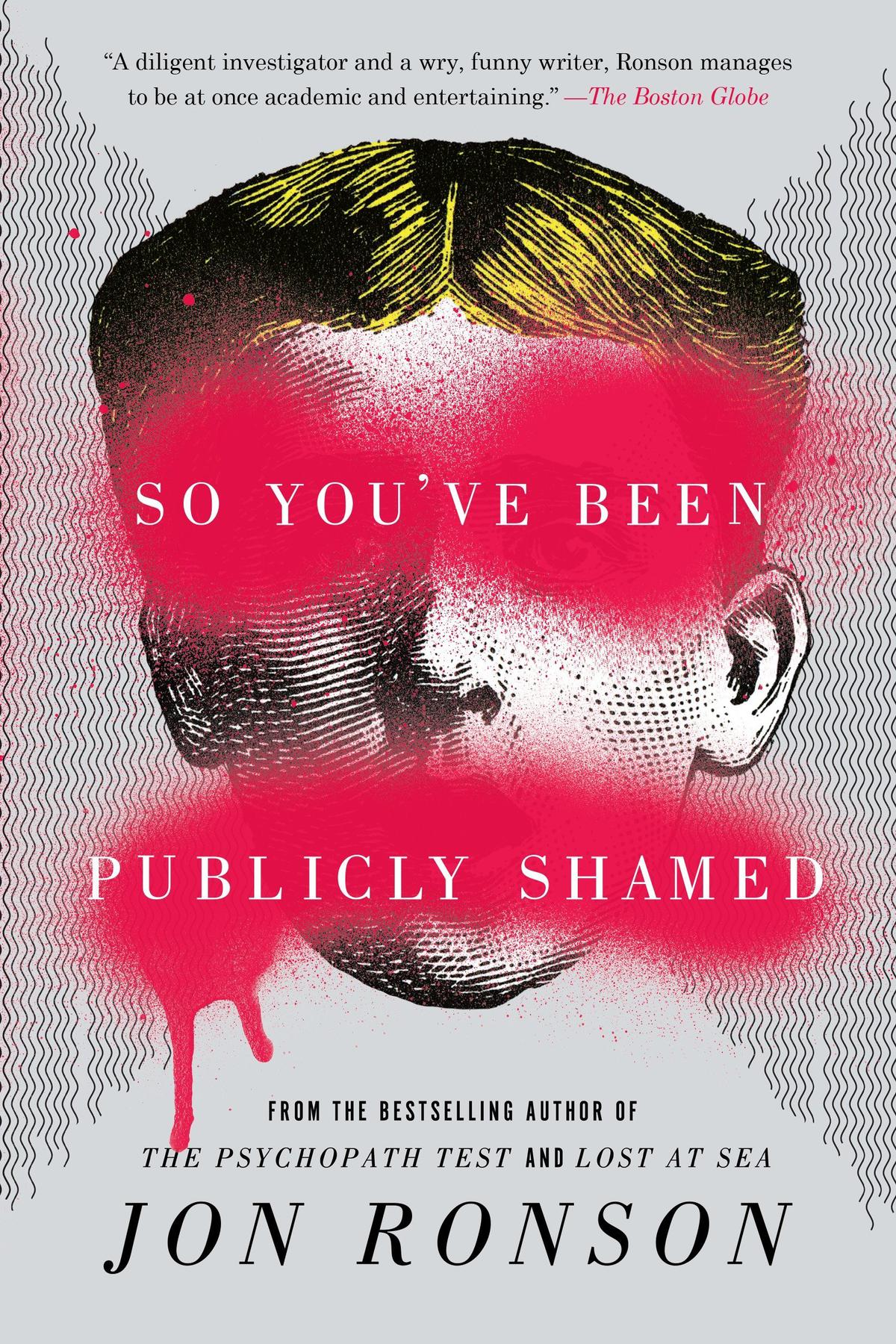

Clockwise from top: Jonah Lehrer, Virat Kohli, Sourav Ganguly, J.K. Rowling, the Dalai Lama, and Jon Ronson’s book So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed

A couple of weeks ago, the internet burst into frenzied outrage because of a video clip that had gone viral. It showed the Dalai Lama, seated in front of a large audience, being approached by a little kid who wanted a hug. The Dalai Lama hugged him and then proceeded to ask the little boy to suck his tongue. It made uncomfortable watching. The boy looked confused and terrified. The people in the audience seemed to be mostly laughing.

It was a difficult video to make sense of. I am not a religious person and I find it difficult to respect people, especially men, who have been given the roles they play. Even so, I found myself trying to figure out a comment to write and not being sure of any of the words that came my way. Two things happened the following day. One, the Dalai Lama published a note expressing his regret about the incident. Two, many people of Tibetan origin wrote that much of what we saw in that video was part of Tibetan culture. I don’t know what to believe. And so, I am a little relieved that I did not comment about this, one way or the other.

The Dalai Lama

The lure of opinions

For more than two decades now, we have been conditioned to opine about everything. As an “extremely online” person, I have spent quite a bit of my time wryly adding my view to not just every little event or incident, but also on other people’s views on the matter. Large parts of the internet are heavily invested in prompting a reaction from us. The more we comment, the more viral the post is. And, I am not going to shy away from saying this, it has been fun. In the early years of social media, the comment section of a blog was the liveliest place to be. I have found many friends from comment threads on LiveJournal. We collected the witty ones, the sarcastic cabal stood together, we booed at the boring ones, we bullied some, others bullied us. It was a whole ecosystem built purely on opinions.

On the internet, it is easy to become a part of the mob. Social media outrage is a powerful thing. Which is exactly why we should be careful about engaging in it.

Then, of course, things became bigger, spread wider. The really opinionated came on and the real arguments began. People began to get increasingly rooted on their stances because to revise an opinion was seen as accepting a mistake, and if there is ever a golden rule, it is that if you accept you made a mistake, you will never be allowed to forget that. It is better to double down than to say you were wrong. And as more sites came up, and we started accessing them on our phones and using every spare minute of every day to scroll down to see who was saying what, we lost every aspect of ourselves except our opinions.

It’s never just black and white

If these years of arguing have taught me anything, it is that things are more complicated than they seem, and that nothing is universal, not even the truth. Something that seems starkly black and white, often pixelates into grey when the camera is pulled back or the angle is flipped. (And now, with artificial intelligence and that whole hoopla, nothing on the internet can be assumed to be true.)

Part of this realisation comes from a book I was reading recently. In Jon Ronson’s So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed, he profiles a bunch of people on both ends of this social media transaction. Those who’d been shamed and those who did the shaming.

In one chapter, he talks about the author Jonah Lehrer, a star writer whose career was on the upswing until a little known, barely published reporter, Michael Moynihan, discovered that Lehrer had made up a bunch of quotes in his book about the singer Bob Dylan. The story and the reaction it got on social media effectively ended Lehrer’s career. But, the book says, the last thing Moynihan felt was the adrenaline rush of validation. “He said he felt as trapped in this story as Jonah was. It was like they were both in a car with failed brakes, hurtling helplessly towards this ending together,” Ronson writes.

Through this fraught journey, I realise I am beginning to have fewer opinions. Social media arguments are often discussed on WhatsApp groups, as friends try to build an army of allies behind them, trying to get more people on their side. These days, I often find myself saying I don’t know. I don’t know enough about the science and psychology of gender to understand whether J.K. Rowling is right or wrong in her opposition of children transitioning too early. I don’t know anything at all about cricket to take a stance on the Virat Kohli – Sourav Ganguly death stare and handshake controversy. (Actual event, not hyperbole). I haven’t studied Tibetan culture to know if the Dalai Lama’s behaviour was customary or creepy. If anything, all of these events have only shown me how little I know about things and how my opinion on quite a few of them is both irrelevant and unnecessary.

Virat Kohli – Sourav Ganguly

On the internet, it is easy to become a part of the mob. Social media outrage is a powerful thing. Which is exactly why we should be careful about engaging in it. We have been screaming for a long time. And things have only gotten worse. So, maybe, let’s just try and shut up a little?

The writer is the author of ‘Independence Day: A People’s History’.

[ad_2]

Source link