A woman named Masarat lived in Phuphee’s village. She wasn’t originally from there, but had married the local school master. I must have been around nine or 10 when she came to the village as a young bride. I remember she gave me a handful of nuts when I went to see her with all the other children.

Every year from then on, we would hear how Masarat hadn’t been able to bear a child. Every year, someone would say she had lost another baby. Initially, people were kind and expressed the grief they felt at her misfortunes, but slowly that turned into opinions and gossip.

Over the years, you could see Masarat walk down the dusty paths of the village and the effort she put into trying to make herself smaller, so that the world might forget that she existed and offer respite in anonymity. But the world had other plans. Masarat didn’t just lose a baby year after year, she ultimately lost her name.

You see, there was another Masarat who lived in the village and whenever a question was raised about a Masarat, the next question was ‘which one?’ People would clarify with ‘yemis ne bachae chu daraan (the woman whose womb refuses to hold on to a baby)’. The other Masarat was blessed with children.

And so it was that even on the days when Masarat wasn’t grieving, a casual but telling glance from one of the villagers would remind her of everything she wished to forget.

Early one afternoon in October, Masarat was carried in by her family into Phuphee’s house. She was miscarrying again, but she refused to be taken to the hospital. Phuphee brought Masarat into her room, ordered water to be boiled, and asked for towels and sheets to be sterilised. One of the helpers was sent off to get maetonji (the local English missionary nurse) and another was ordered to make nun chai (salt tea) for Masarat’s family.

I didn’t see Phuphee come out of her room for a long time. Maetonji arrived and kept bustling in and out of the room, but said nothing. A few hours later, Phuphee and matetonji came out together, and Phuphee walked her to the door. When she came back, Phuphee sat on the floor and said to Masarat’s mother, ‘Asyi karae waariyah koshish magar… (we tried a lot but…),’ and her voice trailed off. On hearing this, Masarat’s mother started wailing and beating her chest and pulling her hair.

‘Oh Allah, I had only one daughter, why did you have to take her? My daughter, where have you gone?’ she wept.

I waited for Phuphee to hug her and try to comfort her, but she didn’t. She just sat there looking at Masarat’s mother without uttering a word. After about 30 minutes, she cleared her throat and said, ‘I want you to remember this grief, this pain. I want you to remember what it felt like to lose your child. And then I want you to remind yourself that this is exactly how Masarat feels about every baby she has ever lost.’

Masarat’s mother looked at her, confused, but you could see the meaning of Phuphee’s words slowly dawning on her.

Phuphee told her to drink the nun chai, which had been placed before her, and then go in and see Masarat. She had lost quite a lot of blood, but would recover, at least physically.

A few days later, Masarat was able to go back home. I tried to muster up the courage to ask Phuphee why she had been so cruel to let the mother think that her daughter had died, but I couldn’t. I had never imagined Phuphee could ever be cruel and the incident had shaken me.

Many years later when I miscarried repeatedly, I remembered Masarat. I called Phuphee and told her about my miscarriage. She asked how I was doing physically and emotionally. She told me to rest as much as possible and to try and talk about how I was feeling.

I asked her why she had let Masarat’s mother think she had died. Phuphee was silent for a while and then I heard her light up a cigarette.

‘When Masarat lost a baby, people would offer their condolences but they would also offer explanations for what had happened. Some would tell her it was god’s will, some that she should have rested more. Others told her not to worry as the stillborn babies would meet her in paradise, but the worst one of all was when her mother told her not to grieve because the babies weren’t real.’

‘Masarat could bear the unfortunate explanations the world gave her, but it cut deep that her own mother kept saying that the babies didn’t have a soul because they died in the womb. That day Masarat refused to go to the hospital because she prayed she would bleed to death. It is not that I don’t question what I did that day, but I know that since then her mother stopped saying that to her. That act of cruelty towards her mother helped Masarat endure.’

‘I must confess, I was also angry that her mother could even think something so awful, let alone say it out loud. I still don’t know if what I did that day was right, and I question myself every so often, but the one thing I was sure of was that it was infinitely easier to have her mother’s grief on my conscience than Masarat’s death. Sometimes healing others comes at a personal price and that day I was prepared to pay it.’

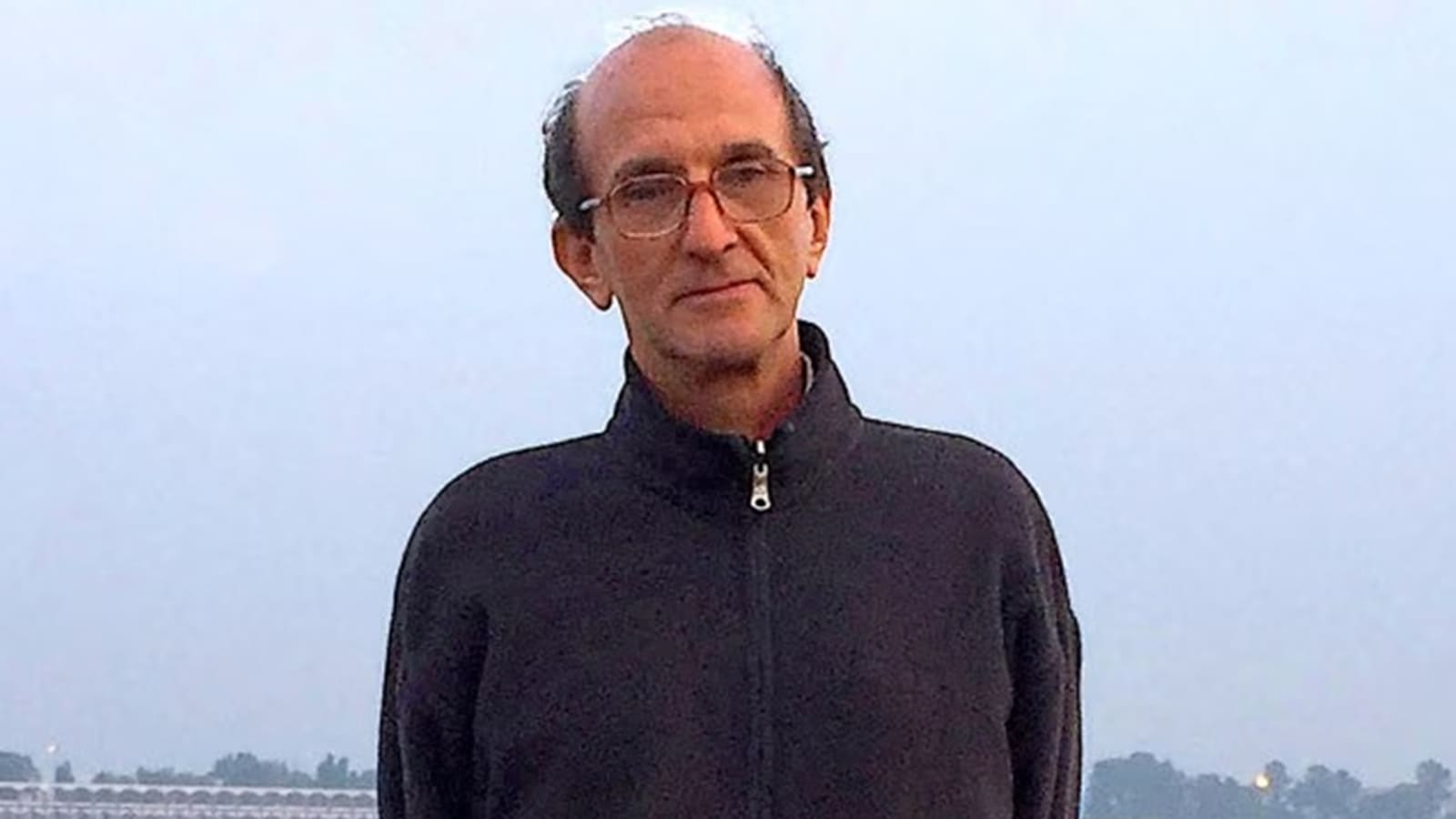

Saba Mahjoor, a Kashmiri living in England, spends her scant free time contemplating life’s vagaries.

.jpg)