[ad_1]

Indian-American author Jhumpa Lahiri’s first novel, ‘The Namesake’, was made into a film by the same name, starring Irrfan Khan and Tabu.

| Photo Credit: Getty Images

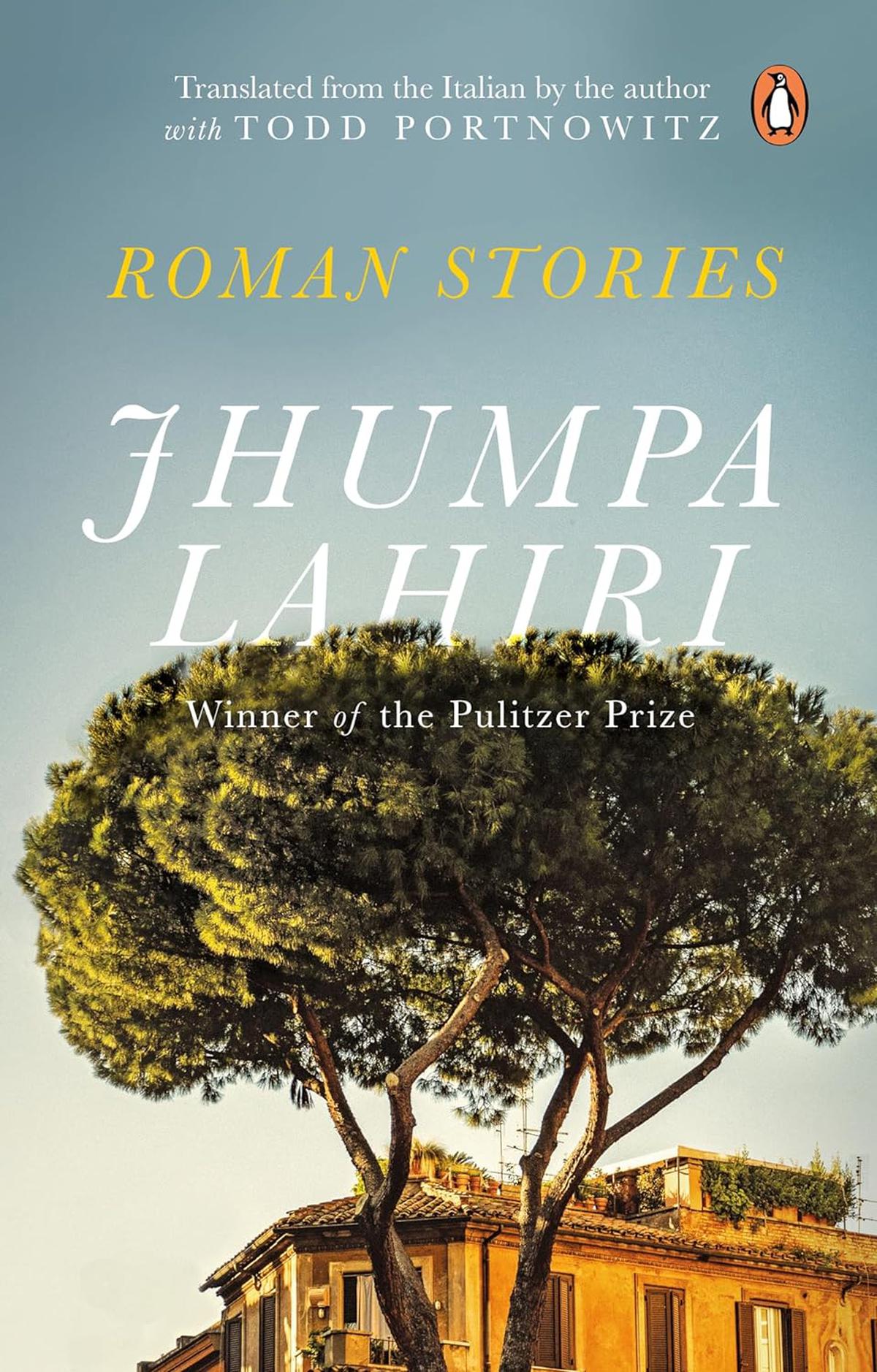

For a book about a city known for its Colosseum and ancient fountains, Jhumpa Lahiri’s latest collection of shorts, Roman Stories, is coloured by new beginnings. Lahiri’s characters are immigrants who arrive on boats, a couple coming to terms with the death of their 12-year-old son, and a widow living by herself for the first time, among others.

This is not the Rome of Fellini films and Patrician women in black dresses who perfume their décolletage. Here, there are red construction cranes on the horizon and the view from the top of the scalinata, known to tourists as the Spanish Steps, is “satellite dishes and smokestacks with impetuous fumes”.

In what is perhaps one of the most daring literary experiments in contemporary times, Lahiri has written only in Italian since she moved to Rome in 2012. Of the 13 stories in the book, she has translated all to English herself except three critical ones translated by Todd Portnowitz.

I had interviewed Lahiri in Kolkata in 2015, not long after her move, and this idea of always feeling like the outsider was a persistent thread in our conversation. I found Lahiri’s deeply-embedded sense of liminality present throughout this book — the houses are on the outskirts of the city, women return to Rome to relive old memories, the men sit on the outdoor tables at trattorias. The essence of Roman Stories is a dark cloud that belongs as much to the ground below as it does to the uncharted territory of the sky.

And who knows liminality better than the immigrant? The first of the book’s three sections is devoted almost entirely to them. They are dark-skinned, politely called la moretta or heckled as ragazza on the street; they wear “long cotton dresses and veils” and speak of homelands with palm trees, crows and dusty roads. In the most devastating story in the book, ‘Well-Lit House’, a young father of five thinks back to the journey to this country after the war killed his grandparents. He remembers the white butterflies flitting above the sea’s surface, almost seeming to lead the way. Once in Rome, however, there are only cicadas that leap out of trees and frighten his wife.

Resonating with the times

Reading Lahiri the week we encountered news of millions of displaced Palestinians was particularly affecting. The idea of othering — the idea of a woman being told by school children that she is dirty and unliked — it is these minor humiliations that lead to big wars. But apart from a single mention of the Bengali word alna in the ‘Notes’, there is no indication that the woman is South Asian. Indeed, the sociological details of the characters seem to matter less than what the city makes them feel.

Not all the immigrants in Lahiri’s stories arrive on boats, however. ‘P’s Parties’ brings together the foreign correspondents, diplomats, and their wives who spend their afternoons shopping for shoes and indulging in leisurely lunches — the Italian way — with mothers of other children who go to the same international school as theirs. But even in these circles, a new arrival is prone to wearing an off-season dress and a “heavy and complicated necklace”. A year later, she is dressed in black “like nearly all the other women in the party”.

Section two’s ‘The Steps’ is a collection of character sketches of those whose lives revolve around the Spanish Steps. Though unambitious in scope, it brings readers closer to the residents. There is an intimacy to lovers being mentioned by a single initial, for instance, like a secret whispered over a glass of amaro.

People sit around the famous fountain Fontana della Barcaccia in Rome, with the Spanish Steps in the background.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

The narrators in Roman Stories vary. It is sometimes a young girl, sometimes a middle-aged man fantasising about an affair, and sometimes a third person observing the action with detached ease. This is where the book visibly falters. In ‘P’s Parties’, for instance, the male narrator isn’t very convincing when he describes beach cover-ups and pearl-grey wool shawls. In ‘The Steps’, a seamstress jarringly comments on a film crew’s “dolly and clapboard”.

Nods to Italian life

Surprisingly, architectural descriptions do not weigh down the book. Yes, there is the romance of the piazzas, bridges, derelict archways and church facades with “a few bricks missing” but it isn’t a sycophantic ode to the city. There are musty apartments with chandeliers that dangle precariously too. There are several nods to the Italian love for tradition and routine and there is food, of course. From glasses of chinotto to hot plates of pasta, from the cotechino at the salumeria to the panettone and pandoro — it is recommended to have some form of pastry around while consuming these pages.

The stories often feel long-wound and unrewarding, but even non-Lahiri lovers will concur that the third section delivers. The four stories here offer the gut-punch reminiscent of her Pulitzer-winning debut book of shorts, Interpreter of Maladies, that with its silver cocktail dress pooled on the closet floor and Mr. Pirzada, the botany professor from Dhaka, carving a pumpkin.

The last story, ‘Dante Alighieri’ is a stunning meditation on the passage of time, and the graceful acceptance of fate. Incipit Vita Nova — Latin for “And so begins a new life” — is the message in its denouement. Profound for a city so proud of its ageing churches and wrinkled faces. This story, this dull golden knife through our chest, is what we have always loved Jhumpa Lahiri for.

Roman Stories

Jhumpa Lahiri, trs with Todd Portnowitz

Penguin

₹499

The reviewer’s debut novel ‘The Illuminated’ is now out in paperback internationally.

[ad_2]

Source link