[ad_1]

Spitsbergen on the Svalbard archipelago in Norway is one of the world’s northernmost inhabited places.

| Photo Credit: Getty Images

The Bruce Chatwins, Paul Therouxs and Ryszard Kapuscinskis of the world may be the more celebrated travel authors, but that doesn’t mean there is a lack of women explorers and writers.

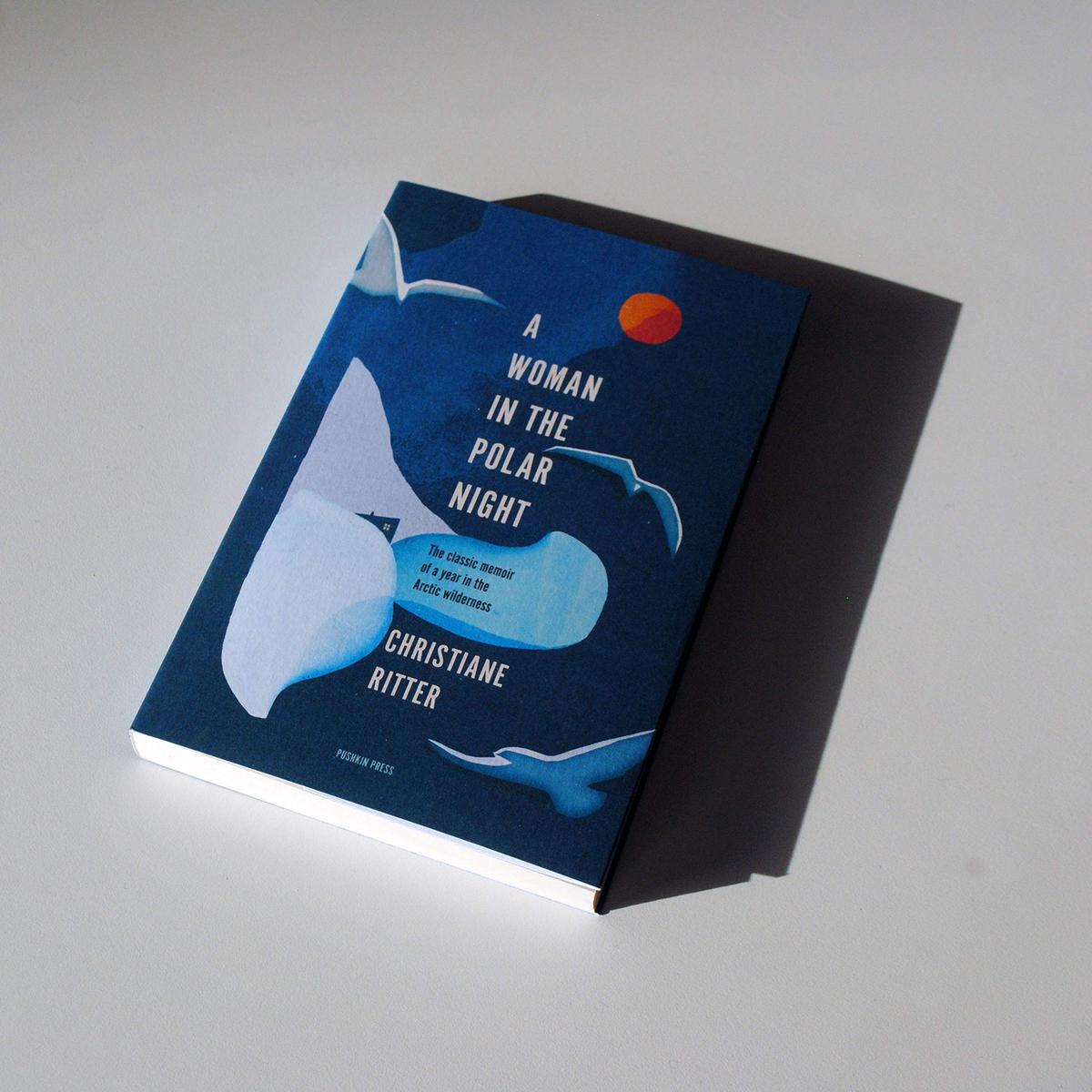

Martha Gellhorn’s Travels with Myself and Another (1978) is still on the bookshelves; so is Dervla Murphy’s account of her Ireland to India adventure in the 1960s (Full Tilt); or Isabelle Eberhardt’s The Nomad, which details her Sahara adventures dressed as an Arab in the 19 thcentury. To that formidable list, add Christiane Ritter’s A Woman in the Polar Night, published in German in 1938, and translated into English by Jane Degras in 1954.

Christiane’s husband, Hermanne, had always dreamed of living in a hut in the Arctic. After taking part in a scientific expedition, he stayed back in Spitsbergen, one of the world’s northernmost inhabited places, fishing in the Arctic in summer and hunting for fur in winter. But for Christiane, an artist, the Arctic was just another word for “freezing and forsaken solitude”, and she did not follow her husband immediately when he wrote to her, “Leave everything as it is and follow me to the Arctic.”

A year at Grey Hook, Spitsbergen

But soon she got his diaries which described journeys by water and over ice, of the animals and the fascination of the wilderness, the strange light over the landscape, and “the strange illumination of one’s own self in the remoteness of the polar light”.

The Spitsbergen mountains.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

There was no mention of the cold or darkness, of storms or hardships. In 1934, Christiane, then in her mid-30s, left her home to join her husband and spend a year at Grey Hook on the north coast of Spitsbergen, and lived to write about it.

In the beginning though, the scene was comfortless. She thought it ghastly country, with nothing but water, fog and rain. At the hut, a “beast of a stove” left the walls and everything else covered in soot, including a pack of cards which had turned black. Her eyes hurt from the unending daylight and then when there was only long night, her mind played tricks. She experienced rar (the Norwegian word for the “strangeness that afflicts many who overwinter in the Polar regions”).

For human company, she had her husband and a genial Norwegian hunter, Karl Nicholaisen. Their only neighbour, a Swede, lived in a hut miles away. She cooked ptarmigan, duck, seal-blood pancakes and steaks from a seal, which had been “laid open like a book”.

The beauty of the Northern Lights

Beautiful Nothern Lights.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images/ iStock

But the magnificent play of the polar night with its Northern Lights captured her imagination. “Northern lights of incredible intensity stream over the sky; their bright rays, shooting downward, look like gleaming rods of glass.” They grew brighter and clearer, in radiant lilacs, greens and pinks, swinging and whirling in a wild dance that swept the entire sky.

A polar fox, Mikkl, drew her attention too and she willed it to go away, to go to another country where there were no people.

When Christiane encounters a polar fox, she sets it free and wills it to go far away from people.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

She begged her husband and Karl to spare his life; when she freed him from a trap, she could never forget his look: “I speak tenderly to him, but the horror does not fade from his eyes.”

It was during several days of a furious storm when she was alone in the hut that she realised the true power of nature; it dawned on her that in many cases it may be more difficult for a man to retain his ordinary humanity in the Arctic than to sustain his life in battle with the elements.

Christiane never wrote another book. She died in 2000 when she was 103, and as Sara Wheeler wrote in her foreword to the book, Christiane always said she learnt equanimity in Spitsbergen. “A year in the Arctic should be compulsory to everyone,” she would say, “then you will come to realise what’s important in life and what isn’t.”

The writer looks back at one classic every month.

sudipta.datta@thehindu.co.in

[ad_2]

Source link