[ad_1]

Every year, around Valentine’s Day, blues music fans from across India and the world meet for an annual date at Mumbai’s Mehboob Studios. They congregate for the Mahindra Blues Festival.

It returns on Saturday after a three-year pandemic-induced interval, marking its 11th edition, which makes it one of the country’s longest-running music festivals. That’s an impressive run for a show dedicated to a niche genre that’s rarely performed on the regular gig circuit.

ALSO READ | India sings the blues

Over the years, the festival has hosted such legends as Buddy Guy, who returns this time for a record fifth appearance, and Taj Mahal, who’s coming back after headlining in 2012. It has also treated us to debut India performances by a long list of blues music stars, including Jonny Lang, Kenny Wayne Shepherd, Robert Randolph and the Tedeschi Trucks Band as well as rising talent like Guy’s protege Quinn Sullivan.

Guy, in fact, is the official ambassador and the main stage has been named the Polka Dot Parlour after the shirts that are part of his signature look. This year, another of his mentees, Christone “Kingfish” Ingram, will visit.

Buddy Guy

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

The tractors roll in

While the origin of the blues has been traced to the mid-19th century when former slaves working on plantations in the deep south of the U.S. developed the music style, the Mahindra Blues Festival has a more prosaic provenance. It was conceptualised by the Mahindra Group to help popularise its brand of tractors among farmers in the U.S.

When the organisers realised that there were already many similar events in the U.S., they decided to hold it in India and position it as a cultural export of a genre beloved of their target customer base. “It seems incongruent that the festival’s here, but it has meant even more to the community,” says Jay Shah, vice president of cultural outreach at the Mahindra Group.

To enable them to experience the festival, the conglomerate has run incentive programmes for dealers in the U.S. through which they get an opportunity to attend. Until a few years ago, it would give every tractor buyer a CD recording of the previous instalment. For the last six years, it has been mounting the annual Mahindra Blues Weekend over two weekends at Guy’s Chicago-based club and tourist attraction Legends, which helps both spread word about the initiative and identify upcoming U.S.-based artists for the flagship Indian edition. Indian-origin Argentinian guitarist Ivan Singh was booked for 2023 after he was spotted there.

Twelve years after the launch of the festival in 2011, Mahindra is among the top 10 tractor brands in the U.S.

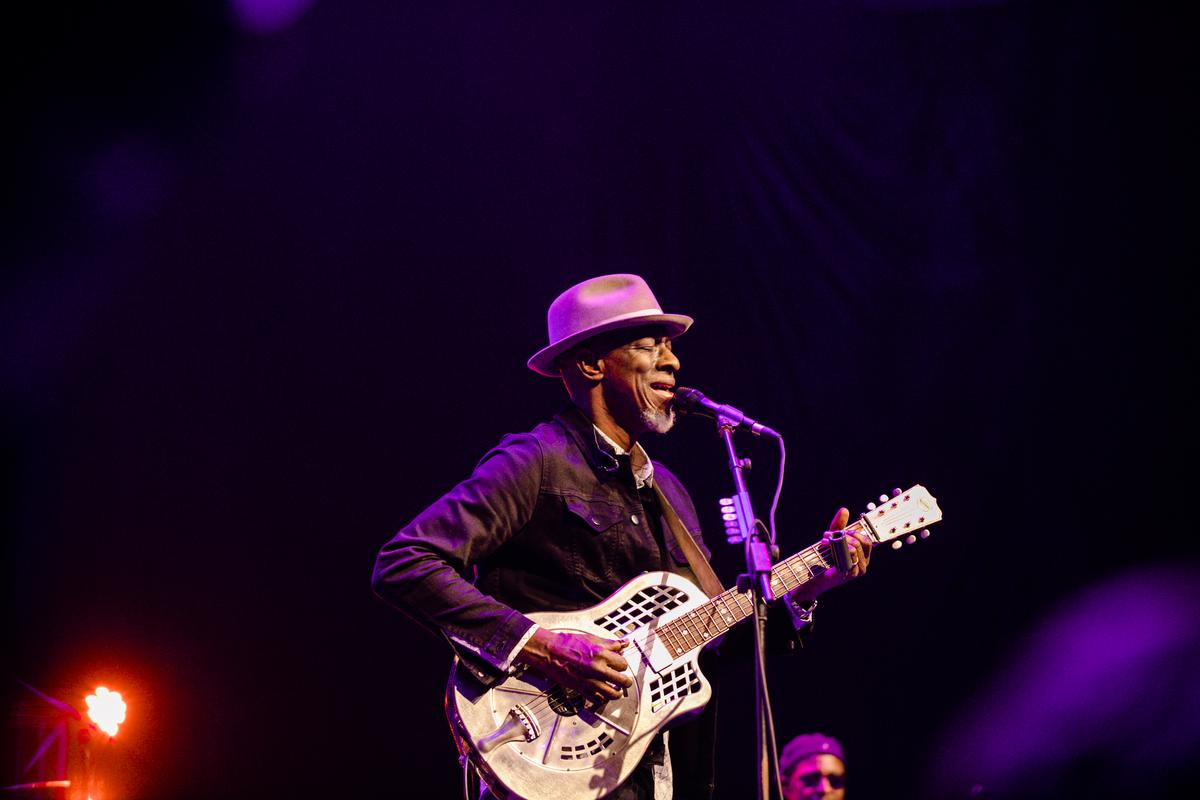

Keb’Mo’

| Photo Credit:

Umed Jadeja Photography

A niche crowd

Limited to 3,000 people, tickets for Mahindra Blues sell out. The promoters have consciously resisted moving it to a larger venue in order to maintain a sense of “intimacy”. The relatively small number is also in keeping with the limited audience for the genre in India, which is loyal, and skews towards the older generation. “In year one, our the core age group was 40 to 60,” says V. G. Jairam, the founder of Hyperlink Brand Solutions, which produces Mahindra Blues. “Now it’s between 30 and 40.”

In order to grow the following for the style, the organisers started the Mahindra Blues Hour, a radio show hosted by Brian Tellis, in 2013, and The Big Blues Band Hunt, judged by composers Ehsaan Noorani and Loy Mendonsa, in 2015. The winners get a slot between the main performances. Notably, only one of them, 2018 honourees the Arinjoy Trio from Kolkata, has graduated to the main stages, indicating that few Indian blues artists manage to establish themselves at a level where they can stand alongside more accomplished international exponents.

Dana Fuchs

| Photo Credit:

danafuchs.com

No woman we cry

Though the Mahindra Blues Festival has always had at least one prominent solo female or female-led act, this year there are neither, which the organisers say is because Dana Fuchs, who performed in 2013, decided to cancel her trip after the recent reemergence of COVID-19. She has promised to make good her commitment in 2024.

Among them is Shillong-based Soulmate, widely regarded as the most popular blues band in the country. The group, fronted by guitarist and composer Rudy Wallang and singer and songwriter Tipriti Kharbangar, has steadily built their fan base since they formed in 2003. Wallang partially credits Soulmate’s rise to Amit Saigal, the founder of the Rock Street Journal magazine and organiser of the Pub Rock Fest and Great Indian Rock series of concerts in the mid-2000s. “They really got us closer to people who hadn’t heard the blues,” says Wallang. “We had an opportunity to connect with younger people, a lot of them coming to these gigs with heavy metal band T-shirts on but curious to know and understand more about this music.”

Some flak too

The Pub Rock Fest took Soulmate to cities such as Baroda, Chandigarh, Chennai and Lucknow. A decade onwards, Saigal is no longer around and touring possibilities have decreased for newer outfits such as Shillong’s Blue Temptation and Jowai’s Quiet Storm, both past winners of the Mahindra Blues competition. “They’re good, authentic bands,” says Wallang. “Maybe because event organisers have to bring them all the way from here they’re not sure they’ll get [enough of] a crowd to make their money back.” Other festivals, which were put together on a smaller scale during the 2010s, such as An Ode To The Blues in Bengaluru and the multi-city Simply The Blues, lasted only a few editions.

Megan Lovell and Rebecca Lovell from Larkin Poe

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

The Mahindra Blues Festival has also drawn flak for repetitive line-ups, especially of the Indian bands. For years, they alternated between Soulmate and Mumbai-raised, Auckland-based composer and guitarist Blackstratblues aka Warren Mendonsa. And while few would be disappointed by the chance to rewatch Guy — Jairam said they had to have him in 2023 because he’s retiring from international touring — for long, there have been demands for more contemporary idols such as Gary Clark Jr.

“We always have the issue of two very big events, which are the Grammys and the Legendary Rhythm and Blues Cruise [taking place in the same month] and some of the acts that we always want getting mixed into one or the other,” says Jairam. As for the minimal representation of local talent on the bigger stages, he believes that the “transition into a world-class act, especially in the blues genre, takes time”.

Thanks to the Internet, blues audiences are no longer confined to the metros. Regulars at the festival include those from Baroda to and Belgaum as well as aficionados from the U.S., Europe, UAE and Singapore. The Band Hunt, meanwhile, receives over 100 entries from acts spread throughout the country. The first winner, in 2015, Aayushi Karnik, for instance, hails from Surat.

A Mahindra Blues concert

| Photo Credit:

Umed Jadeja Photography

But with barely any platforms at which to hone their skills, India’s young blues purveyors find themselves in a chicken-and-egg situation. The lack of avenues remains a challenge for both blues’ proponents and listeners. At ₹5,500 for a season pass, Mahindra Blues is priced on par with other major Indian music festivals but is also out of the reach of some younger audiences. “A lot of our fans can’t afford the tickets,” says Wallang.

Perhaps the blues needs the kind of belief that organisers and venues have entrusted in jazz, a genre that’s enjoying a sustained resurgence.

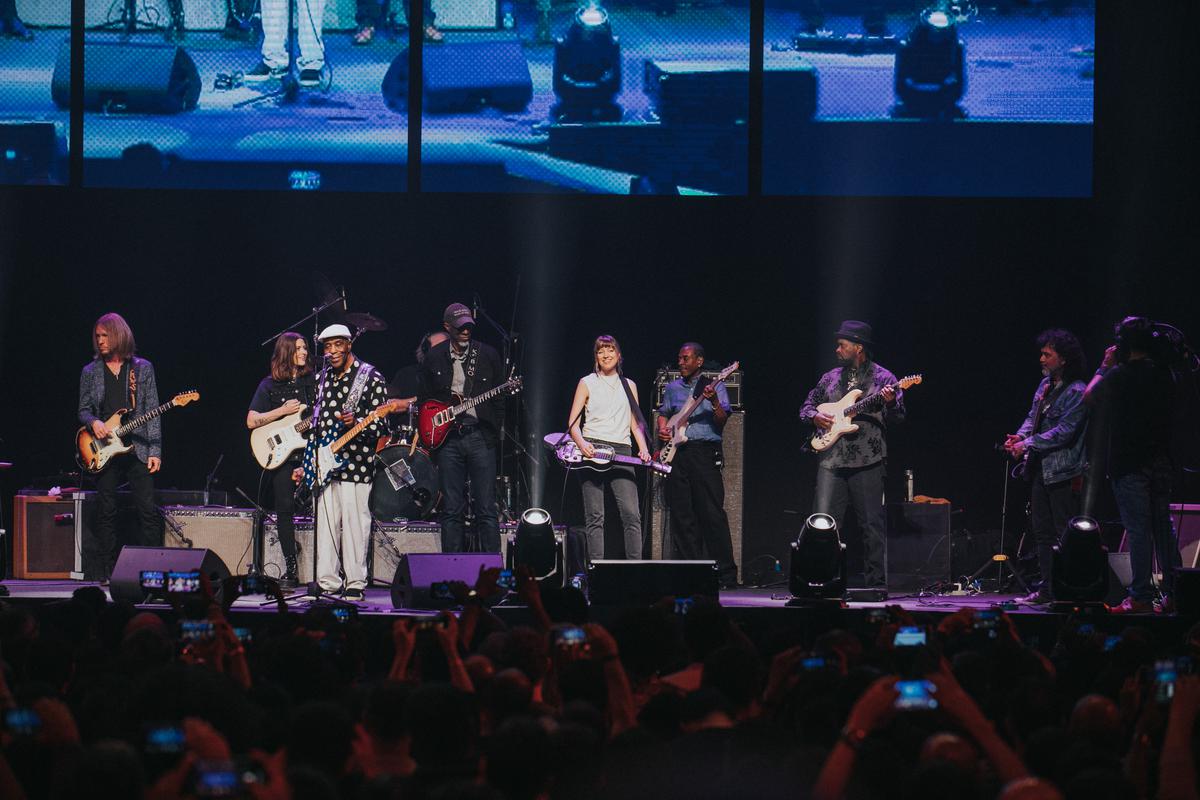

Left to right: Kenny Wayne Shepherd, Rebecca Lovell, Buddy Guy, Keb’ Mo’, and Megan Lovell

| Photo Credit:

Umed Jadeja Photography

PR professional and part-time artist manager Schubert Fernandes, who has attended every edition of Mahindra Blues since 2013, feels “Mahindra could expand their reach to ‘own’ the blues in a more immersive manner”. For example, they could potentially embark on a series of mini versions featuring the top three finalists of the Band Hunt and headlined by a past awardee. Such an enterprise would add more heft to the festival’s tagline that ‘The blues live here’.

The writer is a Mumbai-based journalist who specialises in the Indian music industry.

[ad_2]

Source link