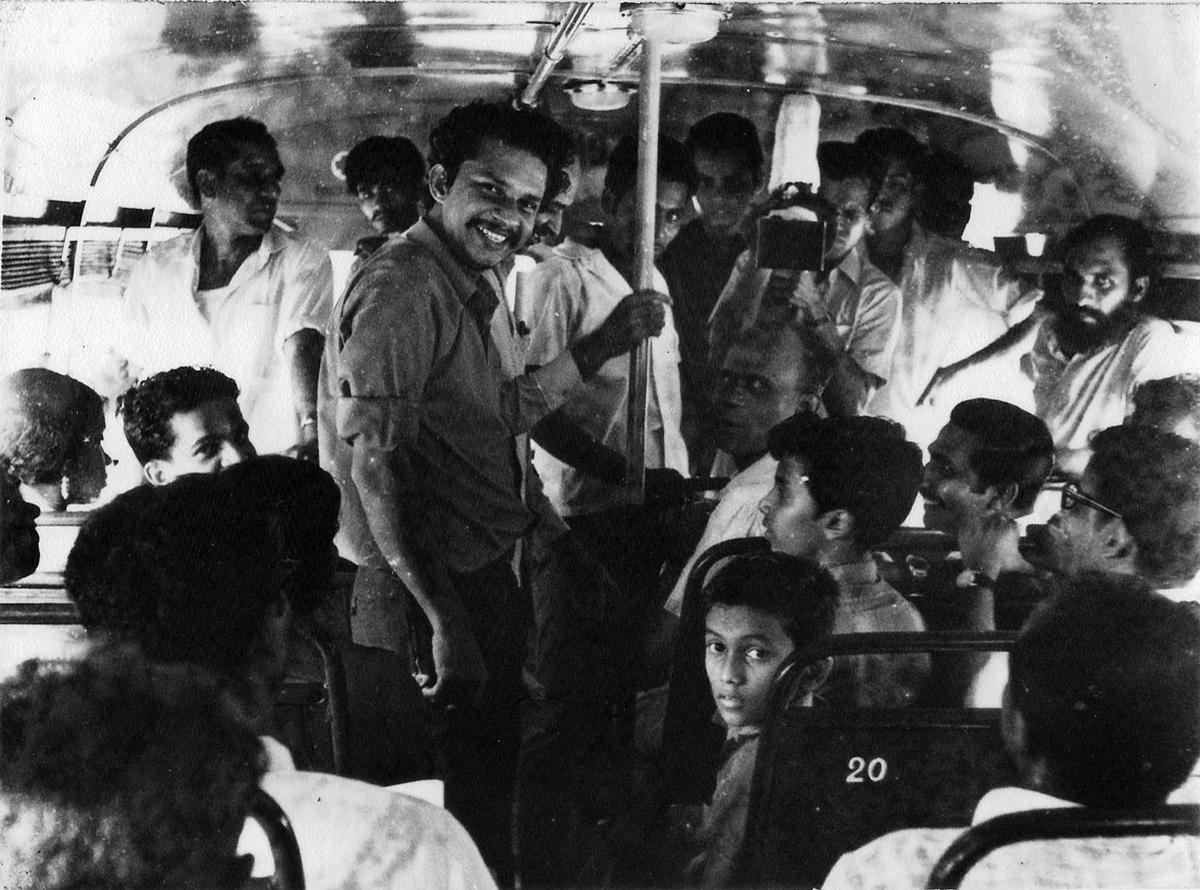

The tumultuous bus journey that a young couple took in 1972 continues to captivate audiences. Swayamvaram remains relevant even 50 years after it first hit the screens and auteur Adoor Gopalakrishnan continues to deftly unravel the complexity of human relationships on screen.

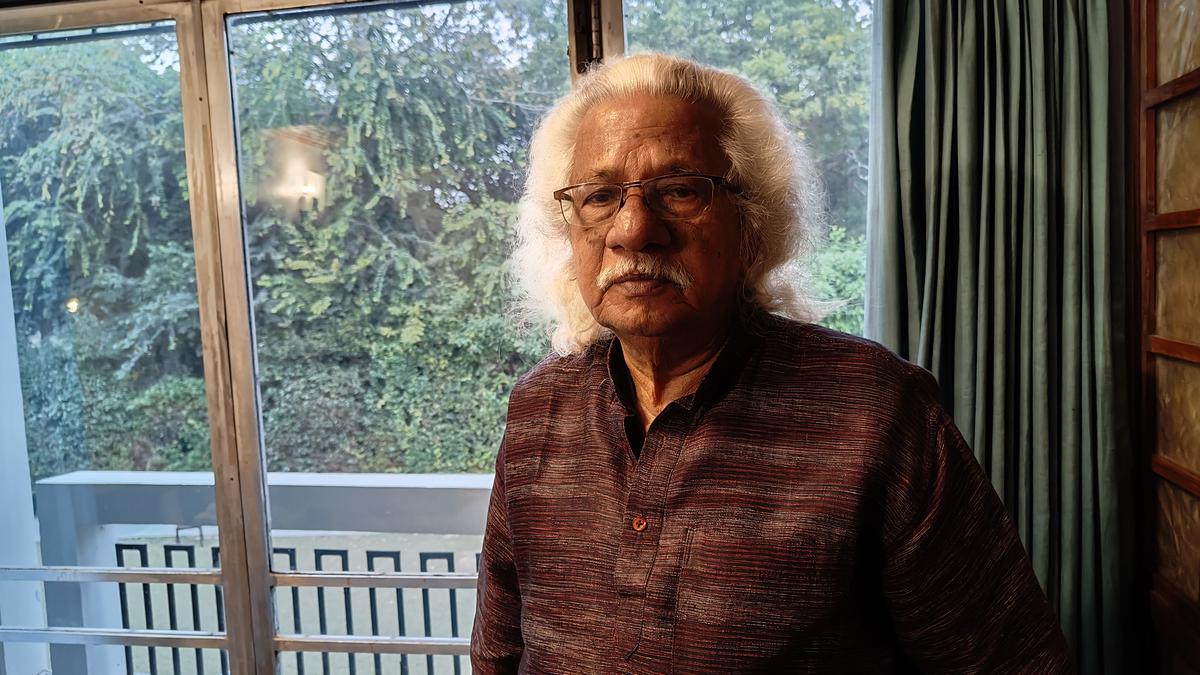

In Delhi to attend a rare commemorative retrospective of his select films organised to celebrate 50 years of his creative journey, the much-feted filmmaker spoke to The Hindu on a range of issues and, of course, his art. Edited excerpts:

Q / What has been your experience of engaging with Delhi?

A /

We cannot avoid Delhi, we cannot escape Delhi! Engaging with the government is neither easy nor interesting. Cinema is equated with Bollywood: The bureaucrats are neither aware of nor interested in anything other than what is churned out in Mumbai. Automatically, we get segregated as outsiders.

A /

My argument was that in this country I am known as a regional filmmaker. To become an Indian filmmaker, I have to go abroad.

Q / Have things changed now with OTT platforms screening a number of films in south Indian languages with subtitles so they reach a pan-Indian audience?

A /

I don’t watch the OTT because I don’t believe in releasing my films for cellphone and laptop viewing. A film is made for a viewing experience in theatre. How could you shrink it and show it on a smaller medium? Cinema is a social experience and is meant to be watched by society in a darkened theatre. Even TV was a compromise but we used to show films on Doordarshan after a significant time had elapsed after the theatre run. It was a secondary source of income, not the intention of making the film. Today, people are making films only for TV viewing which will destroy cinema.

Q / It is being presented as a necessity after the pandemic…

A /

For two years, COVID kept us inside and it led to this demand for in-house entertainment. But cinema, for survival, should not depend on the small screen. Today, even Hollywood is worried about the situation.

A /

When I take the journey up north in trains, I come across hawkers selling grams and peanuts on the running train. They call it ‘timepass.’ I realised they are selling the food item as a way to kill time during the long journey. You cannot think of cinema as a timepass.

Q / What is your take on the idea of ideological censorship and propaganda films?

A /

We are living in the days of Super Censor. First, the films are censored by a government officer and then by an invisible ecosystem on social media. This is ludicrous. Who are these people who sit on a judgment on a film? To me, they are anti-social. When you don’t trust the artist, it is not a very happy situation. Propaganda as a tool is not new to cinema. The Soviet Union did it in a very positive way after the Bolshevik revolution. It was led by the likes of Sergei Eisenstein who devised the grammar of cinema and inspired filmmakers across the world

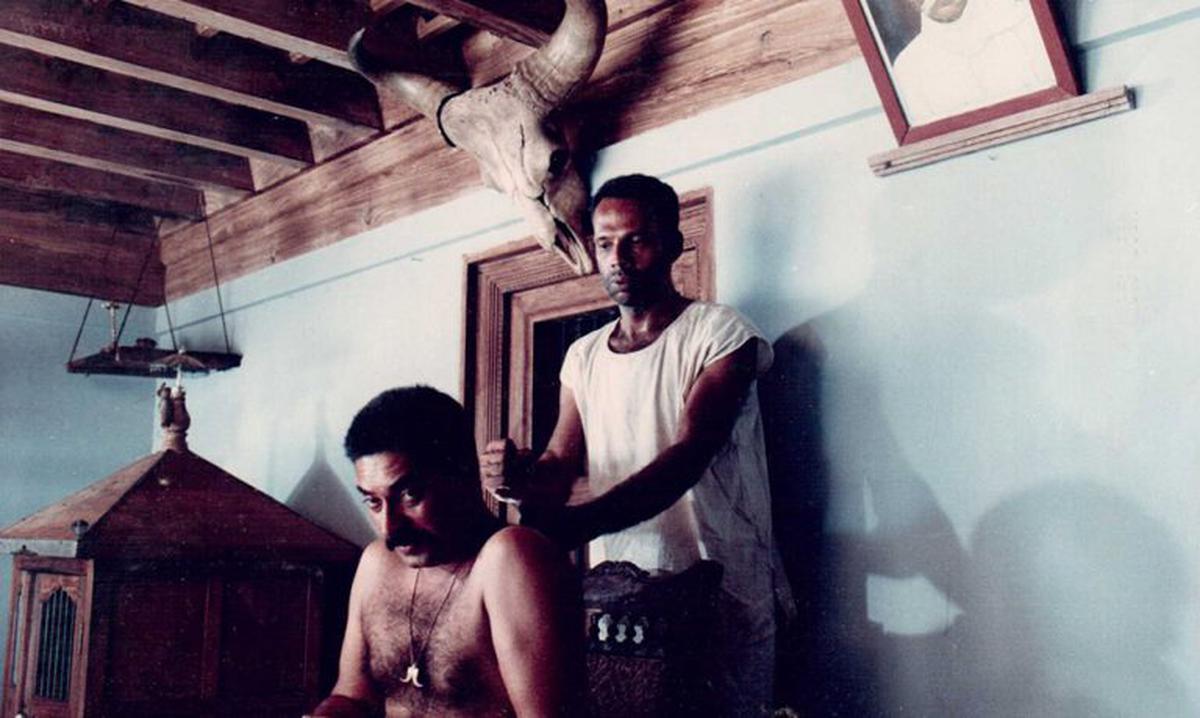

Q / In Vidheyan (1993) it is apparent that your films often deal with the power equation at different levels…

A /

I was always interested in examining the position of a citizen as the very pivot of the whole thing and his engagement with the layers of family, society, and the state. I kept on working on these relationships. For this reason, my films are faithful documents of a period and living. Nothing is fake.

Q / How do you deal with change in technology?

A /

Technology is much simpler now. There is nothing new that needs to be adjusted to. It has become user-friendly. However, the basic requirement remains the same. If you are making a worthwhile film, you have to think beforehand. Cinema, whatever means of technology you use, is essentially a product of thinking. When people used to take years to finish a film, I could complete it in 30 days.

Q / But you take long breaks in between films.

A /

I take time in settling on a subject. It is not because I could not find the money. I could have easily made several films. I make a film only when there is a real throbbing within me to do it. And, in between, I lead a simple life that has nothing filmy about it.

Q / Why do you provide information to your actors on need to know basis?

A /

I don’t want any other interpretation of what I have written. I don’t allow my actors to make any changes to the dialogue. It is quite possible that I change my mind about a particular scene during the shoot. My script is very organic. It can change, it can grow. My script contains not just a scene-wise description of events. It includes camera movement and the composition of scenes. If it is not written, it is in my mind.

Q / Was it always like this, even when you worked with some of the top stars?

A /

Yes, right from my first film where I worked with Thikkurissi (Sukumaran Nair), who was a big name in the Malayalam film industry. My village people asked will he listen to you? I said more than anybody else.

Q / These days younger filmmakers often talk of cinema being a collaborative effort…

A /

When you are not a master of your craft, it becomes a collaborative endeavour. Nothing wrong with that if it works for them.

The retrospective is on at the India International Centre, New Delhi, till December 21

A still from Swayamvaram. Photo: Special Arrangement

Adoor shooting the bus journey in Swayamvaram. Photo: Special Arrangement

A still from Vidheyan. Photo: Special Arrangement