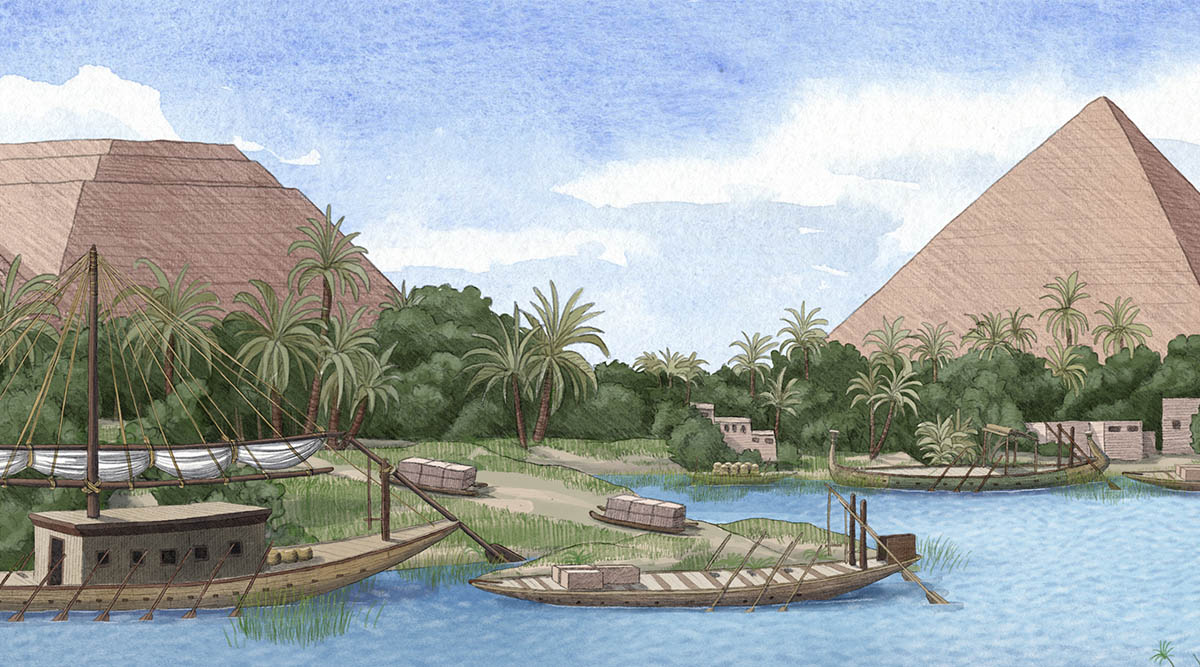

For 4,500 years, the pyramids of Giza have loomed over the western bank of the Nile River as a geometric mountain chain. The Great Pyramid, built to commemorate the reign of Pharaoh Khufu, the second king of Egypt’s fourth dynasty, covers 13 acres and stood more than 480 feet upon its completion around 2560 B.C. Remarkably, ancient architects somehow transported 2.3 million limestone and granite blocks, each weighing an average of more than 2 tons, across miles of desert from the banks of the Nile to the pyramid site on the Giza Plateau.

Hauling these stones over land would have been grueling. Scientists have long believed that utilizing a river or channel made the process possible, but today the Nile is miles away from the pyramids. On Monday, however, a team of researchers reported evidence that a lost arm of the Nile once cut through this stretch of desert and would have greatly simplified transporting the giant slabs to the pyramid complex.

Using clues preserved in the desert soil, the scientists reconstructed the rise and fall of the Khufu Branch, a now defunct Nile tributary, over the past 8,000 years. Their findings, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, propose that the Khufu Branch, which dried up completely around 600 B.C., played a critical role in the construction of the ancient wonders. “It was impossible to build the pyramids here without this branch of the Nile,” said Hader Sheisha, an environmental geographer at the European Center for Research and Teaching in Environmental Geoscience and an author of the new study.

The project was stirred by the unearthing of a trove of papyrus fragments at the site of an ancient harbor near the Red Sea in 2013. Some of the scrolls date back to Khufu’s reign and recount the efforts of an official named Merer and his men to transport limestone up the Nile to Giza, where it was fashioned into the Great Pyramid’s outer layer. “When I read about that,” Sheisha said, “I was so interested because this confirms that the transport of the pyramid’s building materials were moved over water.”

Transporting goods on the Nile was nothing new, said Joseph Manning, a classicist at Yale University who has studied the effect of volcanic eruptions on the Nile during subsequent periods of Egyptian history and was not involved in the new research. “We know that water was up close to the Giza pyramids; that’s how stone was transported,” he said.

According to Manning, researchers have theorized that ancient engineers could have carved channels through the desert or used an offshoot of the Nile to transport the pyramid’s materials, but evidence of these lost waterways remained scarce. This obscured the route Merer and others had taken to reach Giza Harbor, the manufactured pyramid-building hub located more than 4 miles west of the Nile’s banks.

Seeking evidence of an ancient water route, the researchers drilled down into the desert near the Giza harbor site and along the Khufu Branch’s hypothesized route, where they collected five sediment cores. Digging down more than 30 feet, they captured a sedimentary time lapse of Giza across thousands of years.

At a lab in France, Sheisha and her colleagues sifted through the cores for pollen grains, tiny yet durable environmental clues that help researchers identify past plant life. They discovered 61 species of plants, including ferns, palms and sedges that were concentrated in different parts of the core, providing a window into how the local ecosystem had changed over millennia, said Christophe Morhange, a geomorphologist at Aix-Marseille University in France and an author of the new study. Pollen from plants like cattails and papyrus attested to an aquatic, marshlike environment, while pollen from drought-resistant plants like grasses helped to pinpoint “when the Nile was further away from the pyramids” during dry spells, Morhange said.

The researchers used the data gleaned from the pollen grains to estimate past river levels and re-create Giza’s waterlogged past. About 8,000 years ago, during a damp era known as the African Humid Period, during which much of the Sahara was covered in lakes and grasslands, the region around Giza was underwater. Over the next few thousand years, as northern Africa dried out, the Khufu Branch retained around 40% of its water. This made it a perfect asset for pyramid-building, Sheisha said: The waterway remained deep enough to easily navigate but not so high as to pose a major flooding risk.

This shortcut to the pyramids was short-lived. As Egypt became even drier, the water level in the Khufu Branch dropped beyond usability, and pyramid construction ended. When King Tutankhamen took the throne around 1350 B.C., the river had experienced centuries of gradual decline. By the time Alexander the Great conquered Egypt in 332 B.C., the area around the parched Khufu Branch had been converted to a cemetery.

Although the water is long gone, Sheisha believes that identifying how Giza’s natural environment aided the pyramid builders could help to clear up some of the many mysteries that still surround the construction of the ancient geometric monuments. “Knowing more about the environment can solve part of the enigma of the pyramids’ construction,” she said.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

!function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s)

{if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function(){n.callMethod?

n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments)};

if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version=’2.0′;

n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0;

t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0];

s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)}(window, document,’script’,

‘https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js’);

fbq(‘init’, ‘444470064056909’);

fbq(‘track’, ‘PageView’);