[ad_1]

A research team led by Virginia Tech’s Michael Bartlett have developed a glove capable of securely gripping objects underwater, inspired by the octopus. The research has been selected for the cover of Science Advances journal’s July 13 edition.

The underwater environment is not really made for humans. We need tanks to breathe, neoprene suits to protect and warm our bodies, and goggles to see clearly. Similarly, the human hand is also poorly equipped to hold onto things.

“There are critical times when this becomes a liability. Nature already has some great solutions, so our team looked to the natural world for ideas. The octopus became an obvious choice for inspiration.,” said Bartlett, an assistant professor in the department of mechanical engineering.

Many professions like those of rescue divers, underwater archaeologists, bridge engineers, and salvage crews require the ability to use their hands to grip objects underwater. Without the ability to hold slippery things underwater, humans have to resort to using more force sometimes. This can be a problem when a delicate touch is required. This is where the octopus comes in.

The eight-arm cephalopod is one of the most unique creatures on the planet and it can use those arms to hold and grip a variety of things in its underwater environment. Those arms are covered in suckers controlled by the animal’s muscular and nervous system. Each of these suckers is shaped like the end of a plunger and has considerable adhesive abilities.

Once the sucker’s wide outer rim makes a seal with an object, muscles contract and relax the cupped area to add and release pressure as appropriate. When many of these suckers are engaged, they exert a strong adhesive bond that is difficult to separate.

The researchers reimagined these suckers to design a glove with compliant rubber stalks capped with soft, actuated membranes. These were designed to perform the same function as the octopus’s suckers by activating a reliable attachment to objects with light pressure that can be applied to both flat and curved surfaces.

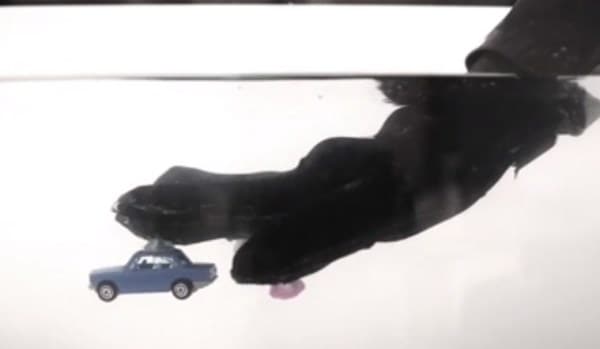

The researchers tested the gloves by picking up different kinds of objects. (Image credit: Virginia Tech / Screenshot)

The researchers tested the gloves by picking up different kinds of objects. (Image credit: Virginia Tech / Screenshot)

After developing the gripping mechanism, the researchers also needed to find a way for the glove to sense objects and trigger the adhesion. Eric Markvicka, an assistant professor at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln was brought in for this purpose. Markvicka added an array of optical proximity sensors that used micro-LIDAR to detect how close an object is. Then, these suckers were connected to a microcontroller to pair the sensing and sucker engagement, thereby mimicking the nervous and muscle systems of an octopus.

The researchers tied a few testing gripping modes while testing the glow. They used a single sensor to manipulate delicate, lightweight objects. They found that they could easily pick up and release flat objects, metal toys, cylinders, and an ultrasoft hydrogel ball.

They then reconfigured the sensor network to utilise all sensors for object detection. After this, they were able to grip larger objects like a plate, a box, and a bowl. They could grip different kinds of flat, cylindrical, convex and spherical objects with the glove even when the user did not close their hands to grab the objects.

!function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s)

{if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function(){n.callMethod?

n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments)};

if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n;n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version=’2.0′;

n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0;

t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0];

s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)}(window, document,’script’,

‘https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js’);

fbq(‘init’, ‘444470064056909’);

fbq(‘track’, ‘PageView’);

[ad_2]

Source link