One balmy July afternoon, a few weeks before I got married, two families from the village arrived at Phuphee’s house. We were sitting on the verandah, tumbling in and out of a light sleep after a heavy lunch of riste te paalak (meatballs with spinach) when we saw them walking towards us. The families were in laws.

‘Aaaze paizihaa aesyii zamdoad batte khyoan [we should have had yoghurt and rice for lunch today],’ Phuphee whispered, as both clans got closer to us. The boy’s father was striding in front. He greeted Phuphee and launched into a barrage of accusations about how modernisation had reached the heart of the village and sown its devilish seeds in every home. Phuphee raised her hand and he was forced to stop mid-sentence. She pointed to the young woman in the group, and asked her to come forward and tell her what the matter was.

‘His family consulted a peer [spiritual doctor] and he told them that my name is cursed. It will bring them misfortune unless it is changed,’ she blurted out.

‘Is this correct?’ Phuphee asked

‘Yes, we have consulted the great Shah saab, and he has told us her name must be changed,’ replied the boy’s father.

Phuphee asked the boy what he thought about this, and he mumbled something that no one present understood.

‘I like my name and I don’t want to change it,’ the young woman added.

‘Amyis chu jinn tchaamut, natte koas koor kaeryi ithpaith kath [she has been possessed by a jinn, otherwise which girl would talk like this],’ the boy’s father said.

Phuphee sat there looking at the girl intently. She called for the helper from the kitchen and whispered instructions in her ear.

A little while later, Phuphee offered everyone sliced apples from her orchard sprinkled with black salt, and a lavender lemonade. The apples tasted fresh and juicy, but as soon as everyone had a sip, their faces fell. There was no sugar in it. In fact, there was no lemon either. It was just water with some lavender in it, which on its own had a bitter tinge to it. The boy’s father said that maybe the helper had forgotten to add the ingredients.

Phuphee replied that the lemonade had been made to her strict instructions.

The boy’s father said he didn’t think it was lemonade. The helper had made a mistake.

Phuphee replied, ‘It is lemonade, I assure you.’

He was getting a little agitated.

‘I don’t think this is lemonade. It is water sprinkled with lavender, dear sister.’

‘Does it matter what it is called?’ asked Phuphee, glaring at him.

When everyone had finished their drink, she told them she would consult the spirits and that they should come back the next day, preferably in smaller numbers.

Phuphee knew that the reason they wanted to change the young woman’s name was because she had failed to conceive after two years of marriage. And the blame had been placed squarely at her feet.

The next day the boy and the girl arrived, with only their immediate families in tow.

‘There is something that can be done that will ‘uncurse’ both of them,’ Phuphee informed the father.

‘Anything you say, sister,’ he replied.

‘They will both have to change their names,’ she said.

The boy’s father looked astounded. ‘That is the most absurd thing I have every heard. Whoever heard of a man having to change his name,’ he sputtered.

‘Jinn chene raai karaan zanaan mohnivis manz, su che insaan sinz kaem [jinns are not biased, they don’t possess people on the basis of gender; that’s the job of humans],’ Phuphee replied calmly.

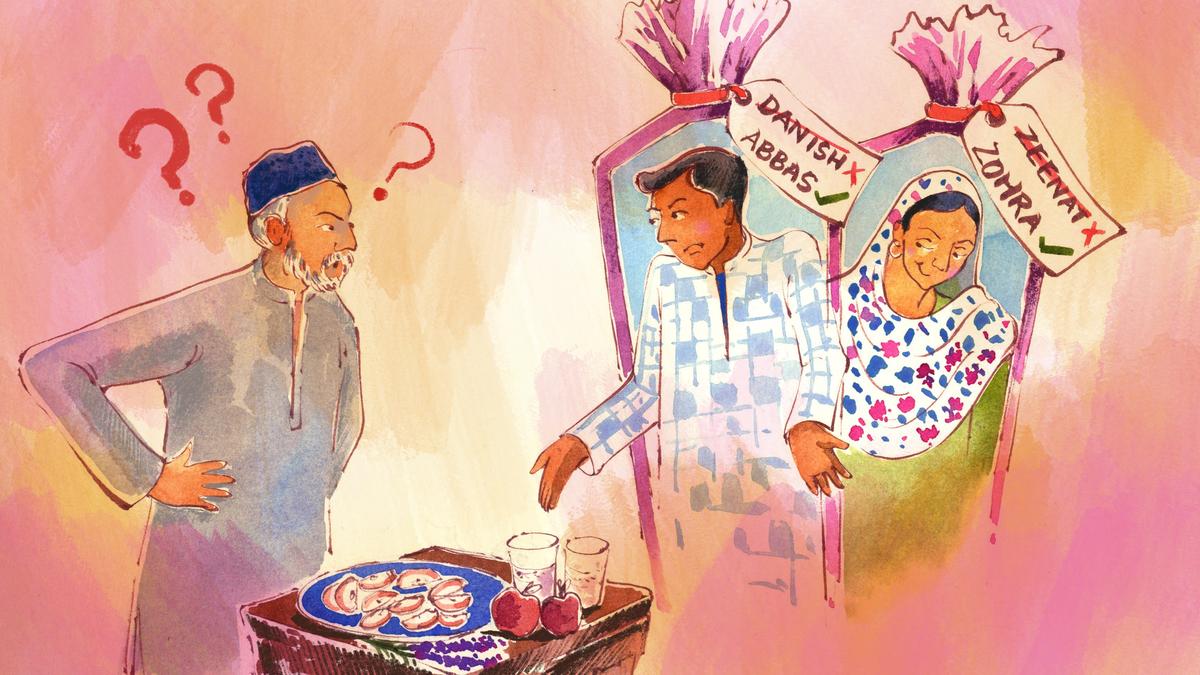

Everyone was silent. Phuphee wrote down two names on two pieces of paper and handed it to the boy and girl. ‘From today, these are your names,’ she said. ‘Remember them well.’

The families got up and left, disorientated by what had just taken place.

I asked Phuphee later why she hadn’t stood up for the girl. Why hadn’t she tried to explain to the boy’s side how ludicrous their ideas were? And what exactly had been the point of changing both their names? I was seething with anger.

Phuphee sat there silently smoking her two cigarettes. When she had stubbed them out in a glass of lavender water that wasn’t lemonade, she said, ‘You cannot change the world by simply asking it to meet you where you think it should be. No, myoan gaash [the light of my eyes], you have to meet the world where it is, and from there drag it, kicking and screaming if need be, to where it ought to be. This situation is not new. Society in general and men in particular seem to believe that women are erasable. As for changing both their names, it was simply an attempt at levelling the field. Who knows, the boy might understand a little about what it feels like to be erased and renamed and repackaged according to the will of another person.’

I was too angry and overwhelmed to really understand what she was saying. But a few weeks later when I got married, I started grasping the reality of what she had meant by erasure. The attempts are stealthily carried out, a bit like drops of rain falling constantly and continuously in one place, gradually changing the geography of the object so that it no longer resembles what it started out as.

Saba Mahjoor, a Kashmiri living in England, spends her scant free time contemplating life’s vagaries.

Published – January 24, 2025 11:28 am IST