As the yellow-green blur of a whizzing auto sweeps by, a string of jasmine lying on the sidewalk quivers from its impact.

The sidewalk faces the long, heavily guarded expanse of Fort St George, now home to the Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly , Secretariat and a host of Government buildings. At one end of Rajaji Salai, the Indian tricolour atop the tall flag mast flutters with gusto like the bellows of a harmonium, giving music to this history-rich part of the city.

The flagmast at Fort St George

| Photo Credit:

The Hindu Archives

As we walk along the contours of the Fort with Sujatha Shankar, convenor of INTACH (Chennai chapter), she traces the brief period of French occupation in Madras between 1746 and 1749. During that time, the French flag flew across the cityscape. “Had it not been for the treaty of Aix–la-Chepelle when Quebec in Canada was exchanged for Madras in India, maybe the French would have continued to occupy the Presidency. It was only after Independence in 1947 that the steel flag post replaced the wooden post,” says Sujatha.

Lush greens of Fort St George

| Photo Credit:

Srinath M

Beneath the flag is the three-square mile area of Fort St George. When two Englishmen, Francis Day and Andrew Cogan, sailed into Madras, the area was established as Fort St George because of a land grant by the Nayak of Poonammalle — a vassal of the Vijayanagara empire. This precinct comprises the church of St Mary’s and the Fort Museum which was originally the trade exchange house.

“Atop the Fort Museum we have the very first lighthouse of Madras. This would send a beacon of light into the ocean when ships sailed in and was used from about the 1700s to the mid-1800s,” says Sujatha.

Officers’ Mess in Fort St George, now the Fort museum. This building housed the first lighthouse in Madras. Photo taken around 1912.

| Photo Credit:

Vintage Vignettes

The precinct also has the house where the Duke of Wellington lived, and what is today the office of the Archaeological Survey of India used to house Edward Clive and Robert Clive. The British and Armenians who had their living quarters within the Fort belonged to the White Town and north of the Fort was the Black Town — home to locals, porters and the working class.

Tracing the years

Sujatha explains that the aforementioned grant of land by the Nayak of Poonamallee was supposed to have been signed on August 22, 1639 the day we celebrate as Madras Day. Before this Madras existed as a series of fishing villages across the coast and settlements near the temples of Thiruvatriyur, Thiruvanmiyur, Thiruvallicane, Mylapore etc.

As we walk away towards George Town, the long shadows cast by the Madras High Court deepen in the afternoon sun. “After Gothic Bombay, colonial Calcutta you have Indo-Saracenic Madras!,” says Sujatha.

Gopikanth L, a student, listens mindfully as Sujatha chronicles the area’s history. He says, “My grandfather had a glass shop in the area. I have grown up playing cricket in the streets of Chennai. It is a city with a soul. Even after moving to Mumbai, when I am in Chennai, I meet my school friends for a quick bun butter jam at George Town followed by uthapams at NSC Bose Road.”

An advocate at the High Court, Vandana Parasuram shares fondly, “From Ninan’s in Parry’s Corner to Gujarati snacks available in the area, cheap and healthy fruit bowls available outside court to thukpa and momo in Burmese street the area in general gives a collective feel. If you have ten or even 100 rupees there is something for everyone.”

“Another thing that my friends and I do when in the area which many don’t know about, is visit the watch tower inside the High Court which is not accessible to outsiders. This was the lighthouse before the one near Marina Beach came up. A dingy staircase leads to the top from where you can see the entire city, ships docked in the port area, cargo being unloaded and activities at the port. It is a very exciting break to get away from the hustle of the court,’‘ adds Vandana.

The Madras High Court was built entirely in the Indo-Saracenic style. The style was a precursor to Modernism. It came about around the 1930s to 1950s. Its origin was said to be in Miami in the United States and it came into India in Bombay. It was an era when mechanisation was being celebrated and simple aesthetic was being venerated. “…devoid of ornamentation, dropping all decorative features and having streamlined simple lines. Cantilever windows and corner windows were features of this style ,” elaborates Sujatha.

Madras High Court

| Photo Credit:

Pichumani K

The blossoming of the style happened in the mid-1800s—an amalgam of various Hindu, Islamic, Buddhist, Gothic, European and Moorish motifs that were employed to Indianise colonial structures.

George Town

George Town gets its name from an event in colonial history. When King George V, then Prince of Wales, visited the Madras Presidency in 1905, to commemorate his visit, Black Town was named George Town.

Nisreen Madraswala belongs to the Bohra community that has strong ties to the area. She says, “Our community comes from Gujarat with roots in Yemen. Bohra means business; we have mostly hardware or pipe businesses. You will see the makan (home) and dukan (shop) concept where the shop is on the ground floor and the house is in the floor above. Previously we had joint families and our families settled in George Town due to its proximity to mosques like the Saifee mosque. However, what I see now is that most of them are moving away from that area.”

Esplanade junction

| Photo Credit:

Jothi Ramalingam

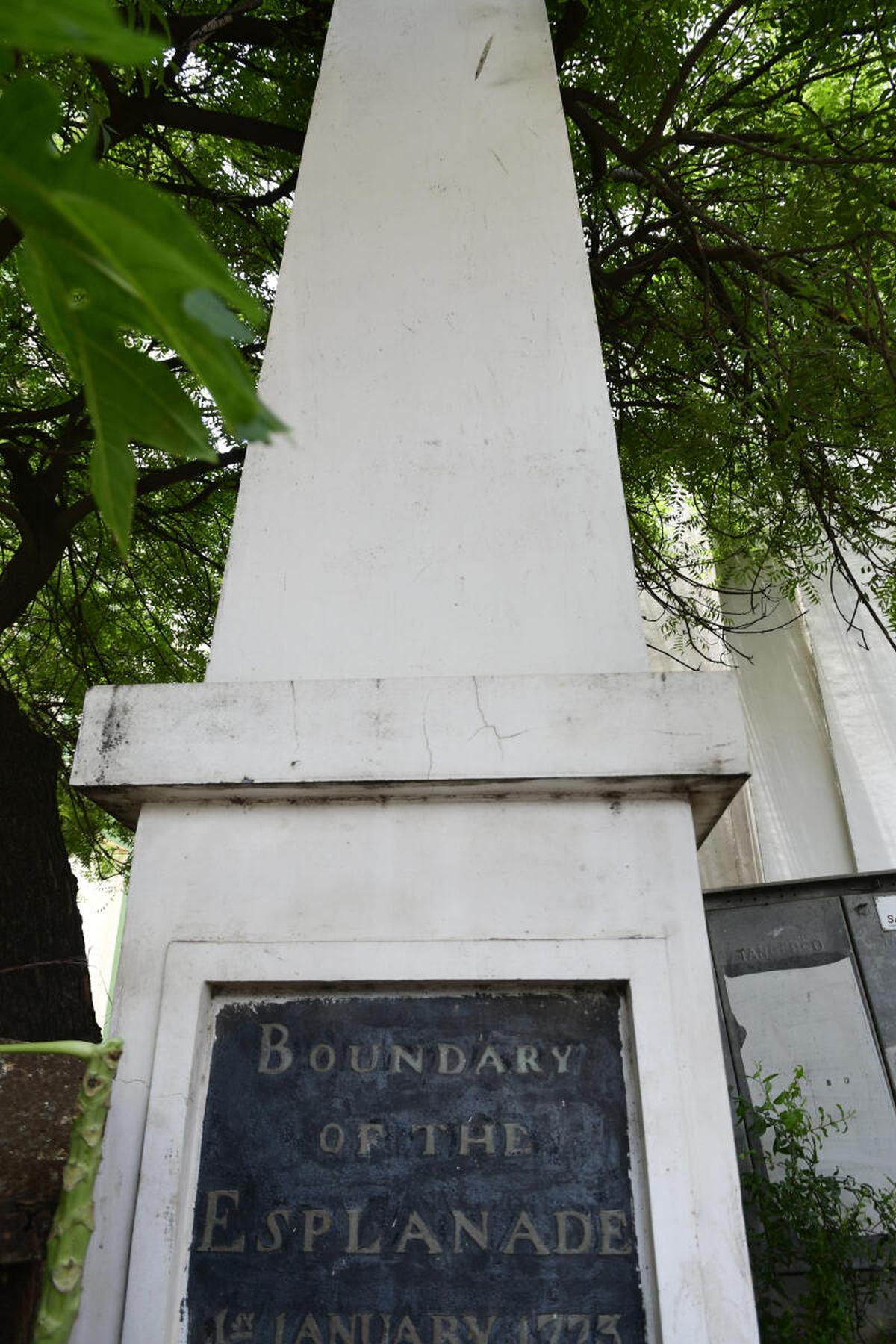

In the 1740s, when the French attacked Madras and occupied Fort St George, they destroyed the Black town. Later, despite the attempt to attack Madras again and the consequent failure of the French in the mid 1700s and 1750, the British decided to have defined perimeters of fire. They cleared out Black Town located in the north of the fort and created an empty esplanade — all of the houses were demolished. To mark the boundary of the newly emerging Esplanade area, a number of pillars were constructed. One such obelisk survives on the left boundary of Hare House which is looked after by Parry and Co.

One of the only surviving pillars that were constructed to define the contours of Esplanade

| Photo Credit:

Srinath M

The newly defined Espalnade area then became the land on which the High Court was built. Sujatha lays out that, “The Esplanade became the new black town — created in a grid pattern with three main roads running from north to south and several intersecting streets running from east to west and several lanes — altogether creating a mesh-like plan, dedicated to special business — in aspects of trade – paper, metal, vegetables, and glass wares. The dedicated market had a very eclectic shop-cum-house structure. It was a dense environment where ventilation came from internal courtyards. Some of the establishments that exist today are the oldest in the city.”

Armenian Church

In the mesh of George Town, a few lanes away from Ninan’s lies the Armenian Church on Armenian Street that was established in 1712. The original church was a wooden one built by the Armenians and removed during the Black Town demolition. Later, the church was recreated in 1772 on Armenian Street.

Chennai’s 311 year old Armenian Church

| Photo Credit:

Srinath M

The belfry of six inside the Armenian Church

| Photo Credit:

Ravindran R

The church has a garden-like setting with a deep verandah “which is a very tropical element that has been incorporated into European architecture. You have the Madras terrace roofing, broad verandas with gravestones below, and the belfry of six bells made by the Whitechapel Bell Foundry in London,” says Sujatha. The Whitechapel Bell Foundry has cast the bells of Big Ben and Westminster Abbey in London and also later for the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia. The ancient church has also seen the publication of the earliest journals by the Armenian publications that were printed in 1794.

As our walk comes to a close, we realise that the cramped and noisy streets of George Town don’t end in black but break out in chance encounters, lovers’ quarrels, teenagers scouring for old coins from the street-side coin shops, lawyers engaging in fierce debate, old friends meeting at Ninan’s for a quick fish fry and caramel custard or a street brawl that gets dismissed like the faint aroma of coffee drowning in the smoky air. With every whiff and brush, the city lives and laughs in colour.

.jpg)